A Brief Deep History Of Ukraine - And Why Putin Hates It

Kyiv represents the true heritage of medieval Rus culture; its independence poses a permanent threat to the ideology powering all incarnations of Moscow's empire

To preface this piece I first want to apologize for overwhelming everybody’s inboxes this week. For some time now I’ve planned to take next week off, and instead of skipping blogging entirely I decided I’d send out a slightly abbreviated post the Friday before.

Then another war in the Middle East broke out and I wound up feeling compelled to write a full post about that. Systems are systems and wars are wars, even if the flavor is different from case to case. And with the usual media coverage of the conflict following familiar tropes, I thought I might as well shout into the wind a little on the off chance it does anyone some good.

Trying to summarize the tortured history of the Arab-Israeli conflict in 6,500 words had the side effect of putting me in the right frame of mind to write out a brief on the deep history behind Putin’s war on Ukraine. As always, I find that a systems-based view revealing, generally doing better than most theories to demonstrate how material forces shape people’s decisions in moments of crisis.

So after giving a brief update on the fighting seen so far this week, leaving whatever happens from Friday to Sunday for my next update, I’ll turn to the history of it all. Putin has staked the entire rationale for this conflict on a totally misbegotten version of history, and it’s worth laying out exactly why.

In the end, it all boils down to raw power. Ukraine is Putin’s precious prize because the story of Ukraine annihilates the foundation of his rule: feeding the delusion held by too many people in his empire that without imperialism and a strong central authority it cannot survive.

That is now true - and the inevitability of the demise of the Russian Federation from world maps in the future is written in Kyiv’s independence. A free and prosperous Ukraine begs the question of why a central government in Moscow should exist at all.

So he must destroy it, whatever the cost. NATO expansion has, for Putin, always been nothing but an excuse, a tool to justify his grip on power to the people who could rebel and end him if they chose to. This is why he did not launch the focused operation in Ukraine’s east and south only, as I and apparently most of Ukraine’s military leaders were convinced was his aim in 2022.

Putin used the desire by world leaders to see him as a rational, predictable actor to power a deception campaign lasting the better part of a decade - something that makes him a lot like the leaders of Hamas. He has always aimed to restore the power and clout the USSR had to the Kremlin. This is his life’s mission, and he doesn’t care how many people die so long as he can claim to be moving towards his righteous goal.

This is a holy war that will absolutely become the next Arab-Israeli conflict if Moscow is not driven out of Ukraine. Not an ideal situation by any means, but it is what it is.

Putin’s New Gamble

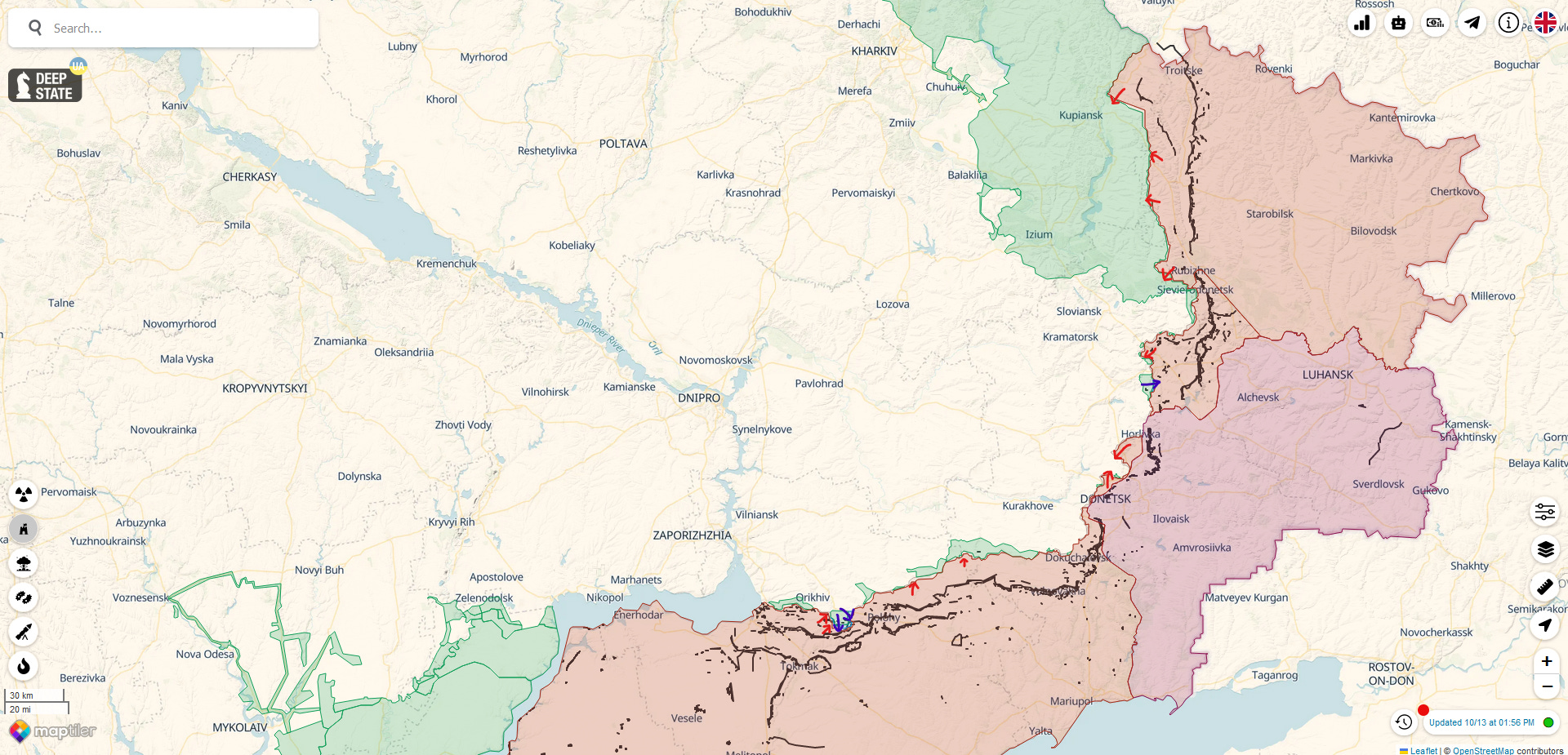

Over the past week ruscist forces have shifted gears, mounting large armored assaults in several sectors with the usual results. The main focus of this mini-offensive is Avdiivka, a small and heavily fortified town that Putin’s troops have been struggling to surround all year.

Not long ago Ukraine mounted a local counteroffensive against one wing of the jaws it has held half-closed all summer. Throwing back the enemy near Optyne helped alleviate the danger of the town - which Zelensky visited over summer - being surrounded.

That seems to have triggered something in the ruscist chain of command, because the heaviest attacks seen in this area in some time have run into minefields and artillery barrages. Apparently watching Ukraine have to struggle through these as it continues the hard job of taking the Surovikin Line’s ramparts made Putin’s officers forgetful of their own inability to advance.

It’s been a while since videos of long columns of armored vehicles packed too close together were this common. Ukraine’s defenders have been taking full advantage of the situation, destroying dozens of tanks and troop carriers over the span of a couple days. There hasn’t been this much footage of ruscist troops being wiped out in summary fashion for more than six months.

The one where some poor orc gets run over by a BMP is just tragic. Especially the deceased’s buddy standing there staring at the armored vehicle like he just realized how stupid it is that infantry can’t easily communicate with the driver to prevent these kinds of incidents. Whatever learning experience the vehicle crew might have walked away with was soon terminated by a mortar round scoring a direct hit.

Look, Ukrainian troops absolutely make mistakes and don’t always perform very well. But for the most part, they are consistently more professional than their enemy. Something you’ll notice if you review a lot of verified combat footage is that ruscist propaganda shots almost always cut away without revealing crucial details. Given their habit of recycling footage, it’s never possible to fully trust what you’re seeing. Ukrainians, on the other hand, usually show enough before and after a given attack to get a sense of what happened and where.

So even though there isn’t an equal or entirely representative amount of footage coming from the front lines, it’s possible to generally state that Ukrainian troops are better drilled than their counterparts. I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen a shot where ruscists act like they’re straight out of basic training. They cluster up, stand around too much, and have a nasty tendency to leave their wounded behind - it seems to depend on whether they’re being closely observed by an officer, though, as there is evidence in recent months of more attempts to take care of their wounded.

That’s not to say the fighting is easy for Ukrainian soldiers - someone is always having to take the brunt of these attacks until the artillery can eliminate the threat. Warfare still always comes down to small groups of men and women slugging it out over patches of cover (do give those who need it anatomically proper body armor, Kyiv. And if you have trouble training women, send a few thousand to the West Coast in a single brigade. We’ll work out a program at Fort Lewis no problem). And the newest ruscist air support technique is to sent in a full squadron of combat jets, 8-12, each carrying two satellite guided glide bombs.

I expect this is a sign of how much stress ruscist artillery units are under - while devastating where they strike, these attacks aren’t as prompt as support from a howitzer or mortar in most cases. While it is possible for pilots to receive and input GPS coordinates in flight, unless you are keeping a lot of jets in the air all the time it’s more likely that every few hours a new pre-planned wave hits, the goal being to use the bombs like a heavy Grad multiple rocket launch system to saturate an area where Ukrainian troops have recently taken control.

Only combat jets and better long-range air defenses like Patriot systems operating within 100km of the front lines are able to interfere with this tactic. Another reminder that massing a lot of people in one area is extremely dangerous in modern warfare - again, Ukraine’s summer campaign might not look like a great success based on square kilometers liberated, but the progress made was highly significant given what everyone learned about the ruscist ability to organize defensive efforts and the damage done to its forces.

The key reasons why Ukraine’s Kharkiv counteroffensive was so successful last year were the steady degradation of local ruscist units by Ukrainian attacks and Moscow’s shocking lack of reserves. By partially mobilizing Moscow was able to substantially increase the size of its army operating in Ukraine; retreating across the Dnipro in Kherson allowed for more troops to be deployed against Ukraine’s attacks, even if many aren’t very good.

Ukraine has worked out its own novel theory of warfare that appears to draw from the idea of people’s war - an all-out inclusive effort by all parts of society to contribute to the defense of the nation however they are able. This presents major management and coordination challenges but also allows Ukrainian forces to adapt more quickly and, as important as the original innovation, spread best practices.

This is not a frictionless process - like any military that expands from several hundred thousand to a full million personnel Ukraine will struggle with scaling up its sustainment and training operations. The loss of a lot of experienced military professionals in the fighting has also made it difficult to teach vital skills to younger officers and sergeants.

That’s part of why I advocate bringing entire brigades from Ukraine to bases in the US for joint training - letting leaders practice their craft in training before putting them through combat is a historically-proven best practice. A citizen army is, on the whole, superior to a fully professional one over the long run because it incorporates diverse perspectives and skillsets that the usual groupthink of military life crowds out, to its lasting misfortune.

Some interesting evidence has emerged of major discontent within the 47th Mechanized brigade, or at least some parts. Having undergone a recent command change and discovering that much of the NATO training given to recruits was close to worthless, the 47th has been involved in heavy fighting for over four months. It makes sense that soldiers are getting tired, though stories about some officers forcing soldiers in non-infantry specialties to clear trenches because the unit has lost too many personnel are concerning.

As effective as Ukraine’s leadership has been overall, both civil and military, naturally there are going to be problems that arise, especially over the course of a long war. It’s important to recognize that when soldiers make public complaints they nearly always have a legitimate basis for doing so even if they don’t see the bigger picture. While never ideal, sometimes being embarrassed is precisely what command needs to accept reality. Raw data is valuable whatever its source.

In any case, Ukraine’s struggles over the summer are less a sign of critical flaws and more of natural growing pains. Ukraine’s armed forces are making a hard strategic transition from a defensive to an offensive posture. This is never easy: responding to the enemy’s attacks is, if you have reserves, always easier than mounting your own.

If someone is trying to hit you and you can back away, it’s usually a good idea to do so. Then keep on doing so if they insist on swinging time and time again. Sure, bystanders might jeer at you for giving ground, but no one’s energy lasts forever. And when adrenaline fades a little and weariness sets in, a short, sharp, vicious counterattack can be overwhelming.

Whenever Moscow tries to mount another major attack, that’s what it sets itself up for. For Ukraine it is vital to engineer as many of these situations as it can - this is the only way to minimize casualties and sustain the fight for the long haul.

Ukraine’s leaders have been open in recent days that they hoped to have liberated more territory by this point, but also that they originally wanted to attack in winter, before the Surovikin Line was completed. The slow pace of equipment deliveries and the lack of key components made it impossible to mount the kind of attack they had hoped to and that most observers - including myself - anticipated.

Essentially, Ukraine fought this summer with a hand tied behind its back. While it is disappointing that the war won’t be over or close to it this year, Ukraine made the right choice in taking a slower and more methodical approach to winning the war.

Evidence is mounting that Ukraine plans to carry out major attacks through autumn, likely aided by a less-severe mud season than feared in spring, which saw a bad one. I have enough of a background in soil and water science to confirm the plausibility of this report from Euromaidan Press, which indicates that southern Ukraine should be able to sustain major operations into December.

The balance of harm done to each side’s recon and drone work is unclear at this point. But as Ukraine continues to absorb ruscist attacks and make slow progress around Robotyne, Novoprokopivka, and Verbove, I think there remains a distinct possibility of the pace on the ground on this front accelerating rapidly without much warning.

Bakhmut has also shown signs of impending movement of late, with ruscist counterattacks here potentially giving way to a renewed Ukrainian push. I think that Ukraine will have to break through north of Bakhmut to have a chance of surrounding the city, but as Kyiv’s forces do not appear to have been mounting a lot of large attacks of late I expect they’re preparing for a push.

It’s a difficult balance from Ukraine’s perspective, engaging the enemy just enough to inflict constant damage while not burning through resources too quickly. I’ve seen references to there being four times as many targets spotted as Ukraine can afford to shell, so the density of fires does seem like the limiting factor in Ukraine’s advance at the moment.

Logistics and training are key to Ukraine’s success in 2024. While the forces engaged on the front line now erode and push back the enemy, any Ukraine can spare have to be training and absorbing modern gear. The first Abrams tanks are in Ukraine, and I have to hope that despite the maintenance requirements on these monsters we’ll soon learn that several hundred more are ready to go.

Ejecting Putin’s forces from Ukraine will cost blood. Ukrainians are by all accounts determined to make the sacrifice. The swiftest way to end the war remains giving Ukraine all the tools it needs to get the job done without delay.

If the Hamas assault on Israel has taught the world anything, it’s that letting conflicts simmer is a bad idea. All you do is make the inevitable explosion worse. And as I’ll try to briefly explain below, this conflict has gone on long enough.

Ukraine deserves to be free and not face a threat of invasion. If anything like a “rules-based international order” is to ever exist, it starts with this principle. And if avoiding a war that drags in all of NATO is the goal, the prescribed course of treatment is the same: give Ukraine what it needs.

Ukraine: The True Heart of Europe

The way Putin tells history, the world more or less began around the year 1600 when Moscow started expanding in the wake of the collapse of the Mongol empire. He, of course, valorizes the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great as something akin to Caesar’s rise - so do all latter-day hangers-on desperate to associate themselves with famous historical figures for political gain.

Whenever anyone references history they face an immediate problem: deciding on a starting date. History really is a kind of “high story,” if you will: a narrative that arranges facts about the past so that there appears to be a coherent logic to major events. All history is constructed, a best guess about the way things were - or as often as not, it’s told as a fanciful tale, usually heroic, portraying events as those willing to pay for the privilege prefer.

History can be treated as a science; fields like archeology, anthropology, and some flavors of sociology, economics, and politics all have a tendency to establish what facts can be determined from an ever-spotty physical record. There are a great many professional historians who hold a markedly different view of their work, however. Much of postmodern philosophy is rooted in the idea that aesthetics triumph over material concerns, and adherents to this view tend to argue that each historical event or time period is unique, impossible to directly compare with others.

I’m a history-as-science kind of person, myself, as aesthetics strays into the territory of morality, which ultimately means you’re making some kind of religious or spiritual argument rooted in faith. While there is nothing wrong with this in friendly discussions, it doesn’t achieve the objective of developing reliable knowledge, the purpose of science. In history’s case, this is a story about the past that draws from all available sources and presumes a certain continuity in human affairs revolving around most people just trying to get by, whatever the place or era.

An odd irony of the false traditionalism Putin and his many imitators around the world claim to be protecting from the dastardly forces of modernity is that their ideology is utterly postmodern. It chooses to elevate an aesthetic about the world that the majority of people who hold postmodern beliefs - who let’s admit generally hail from a distinctly privileged subset of the global population - don’t like to believe is akin to their own because of the open bigotry it embraces.

In reality, like Hitler’s National Socialism and other blood-and-soil movements, Putin’s Russian World is nothing more than attempt to pretend that a particular European Christian group has a God-given right to order the affairs of all the rest. These movements always latch onto history and distort it to portray themselves as defending or restoring some lost glory - hence Putin, as Hitler did, describing his empire as the “third Rome.”

To be fair, people who preach about the so-called “Western” world or “Western Civilization” are doing the exact same thing as these monsters, though they are naturally loathe to admit it. This unfortunately popular concept is essentially a kind of secularized Christianity that tries to replace the old Biblical justifications used to say that Europeans have a divine right to rule the world with something that sounds more scientific and palatable to the modern mind.

Just as the Russian World didn’t begin in 1600 - and had no direct relationship to Kyivan Rus, the medieval polity it claims to descend from - Europe’s true civilizational roots, to the degree distinct civilizations can even be said to exist in the real world, reside not in ancient Greece or Rome, but Ukraine. Though today most students are taught to look to Athens as the origin of concepts like democracy and human rights, these are better seen as universal to most human groups, concepts present in law codes of old all over the world, thought the local form ever varies. The story of Europe’s real heritage lies in the interactions between three very different ways of life in the ecological boundary region that today comprises Ukraine and the Caucasus region of the present Russian Federation.

Long before Athens and Rome - at least several thousand years, to be precise - Europe was dotted with settlements. Evidence is of course scarce, but the more that emerges the clearer it becomes that complex and even semi-urban communities were widespread, especially in coastal areas and the vast steppe of Eurasia that stretches from southern Ukraine all the way to Mongolia.

About twelve thousand years ago the world emerged from the last ice age, and from warmer refuge zones in Iberia and the Balkans humans re-colonized the rest of Europe. They were mainly hunter-gatherers, a lifestyle that is a lot more leisurely than commonly imagined, if ever vulnerable to environmental shifts.

For several thousand years they were Europe’s only inhabitants. Then, in Mesopotamia, folks worked out the rudiments of organized agriculture. Hunter-gatherers have, in the places where they could, the old Pacific Northwest of North America being an excellent example - built complex social orders even while people constantly moved around following food sources. But the choice to live in small farming villages that stayed in place was a new lifestyle, and the advantages to it made the communities who adopted it prosperous and numerous.

Before long waves of settlers were heading into old Europe, encountering the locals. Fortunately for both groups agriculture and hunter-gathering are lifestyles suited towards different environments, so it appears that agricultural communities chose fertile zones while their predecessors tended to pull back into mountainous and wooded areas to avoid conflicts. Because of the high cost of warfare in these times when labor is the primary form of wealth and protection communities had strong incentives to work out ways to cooperate, and trade then family relations slowly bound them together.

Fast forward a few thousand more years and a new group of people appeared in Europe to repeat the process. On the steppes of Eurasia someone figured out how to tame and ride horses, and everything changed for everyone. The partnership between horse and human allowed communities to range widely and manage larger herds of sheep, goats, and above all else cattle. All of a sudden life wasn’t totally dependent on the weather, as a herd functioned as a store of food in hard times. Better yet, if an entire region was affected by a shift in the climate, the entire community could pick up and go somewhere else.

Ukraine is where these three life-ways, hunter-gatherer, agriculturalist, and nomadic herder first intersected in Europe. The meeting was not always peaceful, but neither was it marked by constant war, either. In reality the relations between groups appear to have depended mainly on the climate - Eurasia’s is impacted by a long cycle of shifts between drier and wetter modes. The steppe region, forming a boundary zone between the wetter forests of the north and deserts to the south, is highly sensitive to precipitation shifts.

Every four to six centuries for the past six thousand years has seen a massive influx of herding communities leaving the steppe regions to evade climate change. This naturally transformed ancient Europe into a tapestry of different cultural groups, thousands of small communities bound together by familial and trade connections.

Ukraine was where this first began, and as a boundary area where forests, rivers, and steppe came together it supercharged the development of new identities, generating social developments that cascaded westward. The traces of the long process of peoples merging and splitting across the ages can be found today in Europe’s languages, of which nearly all are Indo-European. This is the name, along with Caucasian, that was used back in the 19th century to describe these peoples when philologists began to develop what became the modern theory of linguistics.

Oh, and for those who imagine that Europe is an inherently light-skinned part of the planet, I have hard news: the first two groups of people to occupy the continent did not have light skin. This trait entered the European gene pool from the steppes, with light skin being a mutation that has occurred in several populations in northern latitudes across Eurasia. Descendants of northern Europeans today don’t tend to have lighter skin and redder hair than those from the southern end of the continent because of their relative exposure to sunlight (at least, not just because of that). Northern Europe just happened to be more easy for herding peoples to occupy long ago because that lifestyle can keep a family alive across several bad winters. More of them meant more light skin genetics in the population.

One of the more fascinating aspects of intensively reading Norse mythology over the years is that these tales - written records first appearing in this region about a thousand years ago and capturing the state of ancient oral legends in its form at that time - directly echo the tripartite heritage of Europe in its stories about the three main groups of gods in the cosmos. The Aesir, Vanir, and Jotnar communities all have their own distinct flavors that track extremely well with the original three European estates, so to speak.

Much of the Eddas, especially the cosmological account known as Voluspa, are fragments of an epic drama about the merging of these three peoples into a single system - roughly, as it goes. After a bitter war between Aesir and Vanir the two unite, holding court over the recovery and doing business with the enigmatic Jotnar who appear both as allies and adversaries to the new order.

Greece and Rome emerged from this sort of process, as did the Celtic peoples of the Atlantic seaboard, the old Norse, and ancient Slavs. These cultural and linguistic groupings are the residue of generations of interaction that make claims about civilization starting in Athens utterly ridiculous.

Even in the days of the ancient Greeks an old and highly dynamic culture existed in the steppe regions. Greece itself was a peripheral outpost of Europe that was more closely bound to the emerging dynastic city-states in Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent than the rest of Europe. Most of what are now assumed to be Greek ideas dreamed up by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle were likely - as elite knowledge is today - borrowed or outright stolen from some deeper intellectual debate taking place in richer places.

It is notable that when Alexander of Macedon decided to conquer the world with his daddy’s army he didn’t head north, but east: the direction from which all of Greek’s troubles came. The peoples it traded with north of the Black Sea were strange and fierce, and anyone of cultural importance looked towards Persia or Egypt to decide what ways to imitate. Until Rome and Carthage developed the entire Mediterranean region was, in an economic sense, utterly bound to the Middle East and the trade routes by land and sea stretching to China.

The reason we are taught to imagine Greece and Rome as the founts of Western Civilization is basically that a lot of rich people in the past saw themselves as carrying on the traditions of these supposed pinnacles of the classical world. Ironically, most of what was ever said by an ancient Greek is only known because Greekified elites inhabited urban centers across the zone Alexander conquered. Even though their political power was soon gone, the families who settled to administer the brief empire built lives and connections and carried on.

But back when the modern mass education system was being put together in the twentieth century this old story about the Greco-Roman heritage of Europe was still very popular - as it remains today. Every story needs a starting point, and at the time, this was as good as any. It also just so happened to enshrine that old Greco-Roman elitism, forgetting that these were not egalitarian or meritocratic empires, but slaver societies where a lucky few exploited the fast majority for personal gain. Democracy was only for the property owners, and naturally their ranks were limited.

Ukraine and the rest of Europe notably lacked massive dynastic empires dominated by elites bent on becoming god-kings until Greece imported the Mesopotamian idea and Rome spread it with its conquests. Trying to re-create the Roman Empire is what every European ruler with delusions of grandeur has attempted to do: this is what makes Putin’s murderous assault on Ukraine so classically European and Western in character.

While Greece and Rome did their thing, the eternal cycle of Eurasian climate shifts kept on driving periods of migration that upended the landscape. The Huns were another steppe people heading west, though more organized and brutal than most. And after they dispersed across eastern Europe, the region settled down again - for a little while.

The flip side of the great Eurasian migration pump is that sometimes the northern parts of Europe experience a rapid increase in population as the climate improves. In the wake of the Hunnic migrations this happened again, right about the time Rome was falling apart - a major volcanic eruption that collapsed the social order of the Norse peoples likely helped set the stage. Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and some Frisians jumped across the North Sea to become the Anglo-Saxons of post-Roman Britain. Eventually, these migrations culminated in the Viking Age, a last pulse of movement by Norse peoples taking advantage of improvements in shipbuilding and navigation to become renowned traders - and raiders and settlers, opportunities depending.

They forged a trade network that passed down the long rivers of eastern Europe to link the Baltic region with Constantinople and even Persia. Along the way they encountered many peoples, many of them happy to establish a lasting relationship with passing traders who could also act as muscle in local disputes. Some of these Vikings settled down, becoming chieftains and other prominent community leaders, as in the rest of Europe. Kyiv and a number of other prominent cities in Ukraine trace their roots to this time just like many in Britain, Ireland, and elsewhere.

Kyivan Rus was an alliance of settlements bound by family ties, like most polities of the pre-Christian world. The Novgorod region, centered around today’s St. Petersburg, and several other areas were all part of this same network. To their south and east were steppe peoples; a bit west other Germanic migrations had merged with the Hunnic and Magyar remnants to fill out the Slavic linguistic zone.

Christianity came to Ukraine and the other Rus lands from the south, likely thanks to the Kyivan people’s close trade links to Byzantine Constantinople. Unlike Western Christianity, the Eastern church spread less through conquest and more by elite transmission - it was advantageous for Rus leaders to adopt the faith of their wealthy trade partners, and being pagans it was not difficult to incorporate Christ-worship alongside other practices.

The Christian Church of the early Medieval ages was very different from what it had been during the centuries after Christ. Originally attractive to slaves and other peoples oppressed by the Romans, as Rome collapsed as a political force and the incoming Germanic groups began settling in the former empire - mostly on lands neglected by the urban and estate-oriented Romans - Roman community leaders found it useful to convert to retain power over their slaves and other lower-class folk. This gave them the opportunity to set themselves up as priests with the sole ability to define Christianity for everyone else thanks to the fact they were literate, offering access to the written scripture that they transformed into a kind of divine oracle in replacement of whatever rituals their ancestors performed to Rome’s pagan gods in olden days.

Medieval Europe and the seeds of the nations that later emerged was created by an alliance between this new Church and the State created by the territorial boundaries of the Germanic chieftains who now handled all military affairs in the former empire. Leaders in pre-Christian European communities lived in an almost proto-democratic arrangement where their authority was limited by a conception of individuals having certain inherent natural rights. Mutual obligations between the leader and less powerful members of the community restrained them from abusing their power, even if the relationship was obviously never entirely tranquil.

Christian priests offered these chieftains something new: status as divinely-mandated kings whose temporal obligations were tempered by being God’s agent. So long as Church lands and the right to levy taxes in the form of enforced donations were sacrosanct, the State could enforce its own tax payments and decide matters of war and peace. It was never a perfectly stable relationship, but it had one clear effect: the free smallholders whose labor and arms had previously kept chieftains in power slowly lost what they had, mostly reduced to peasants alongside their former thralls - an unfree status similar to slave but not permanent or hereditary as in the Greco-Roman system.

The incentive to build wealth through war was built into the medieval European system. In one of those ironies of history generated by the fact that for most of the past thousand years only people of highly privileged social background ever got to write history, the astonishing brutality of the nascent feudal system is downplayed. Where most people are led to believe that the Viking Age was all about rampaging pagans, there is substantial evidence that it wasn’t more violent than any other period. Christian monks in Britain and France emphasized Viking brutality and portrayed it as random slaughter when most evidence points to an era of heightened conflict overall as a result of Christian crusades into Northern Europe under Charlemagne.

In Ukraine there appears to have been much less violence involved in spreading the Christian faith. Here the pattern was more of wealthy and prominent individuals adopting it because this simplified relations with trading partners in Byzantine lands. Christianity at its core is quite a radical faith, flexible enough to be translated into the mythological traditions of most peoples, much like Islam. The concept of leaving vengeance to God is its key social highlight, as in situations where people lack trust the only way to establish a common language is often to engage in a vengeance cycle until all parties recognize how futile these are.

Christianity aims to create a world where vengeance is unnecessary because all evils done will be judged by God at a later date. In an ideal world, this avoids cycles of violence from starting up. Unfortunately, this aspiration founders on the shoals of human mistrust - when people feel wronged as individuals or a group they feel a strong need to see the offender pay a price. So far, leaving vengeance to God or the State has never eliminated it from human society through law or moral compunction.

Kyivan Rus went Christian over a thousand years ago, and the faith apparently coexisted just fine alongside Muslims and Pagans and probably Jewish communities too - their diaspora had already extended as far as China, after all, so it is impossible to imagine there weren’t communities in Ukraine, where many still live today. Though every country has its trouble with bigots, Ukraine appears intent on continuing its ancient heritage as one of the world’s great cultural crossroads.

For centuries this nascent Ukraine carried on - then the Mongols came, the next iteration of semi-nomadic horse riders heading west as the climate worsened. The Mongols are another people whose savagery is intentionally over-stated by written sources that mostly come from their victims. However, there is no doubt that to anyone who opposed them - refused to pay tribute and bow to the Khan, basically - they showed no mercy.

The Mongol theory of warfare was that, as a nomadic people, its best bet when dealing with urban areas was to wipe out a prominent one then use the threat of annihilation to secure the submission of others nearby. And submission was by no means a terrible thing: the Mongols mainly wanted resources and a guarantee that nobody would mess with their interests. Ghengis Khan’s empire built a kind of Pax Mongolica that led to the Silk Road becoming a safe and secure highway for trade across the entire Eurasian Steppe and was noted for its religious tolerance - again, so long as you didn’t cross the Khan.

Kyiv, unfortunately, was destroyed and ruthlessly sacked after resisting, as Kyivans do. Most of modern-day Ukraine was carved up into Mongol tributaries, with the local horde branch playing divide and conquer to keep them from uniting in rebellion. One of these was the small duchy of Moscow, an offshoot of Novgorod that occupied a strategic piece of high ground in the middle of the old Rus territory.

After several centuries passed the Mongols had turned to fighting among themselves and their empire dissolved. Throwing off the Mongol yoke Novgorod became a prominent trading center at a time the Baltic Sea was again becoming a vibrant economic zone after the Black Death. But Muscovy and several other Mongol tributary states, always closely tied to the rest of Europe by marriage ties between aristocratic families, swiftly followed the pattern of the rest of Europe where petty emperors imitating Caesar tried to swallow up weaker neighbors.

Long story short, Muscovy won this long war, swallowing up Novgorod and the others, Ivan and Peter and Catherine forging what their propagandists proclaimed to be a Russian Empire even though the Rus people had long before ceased to exist in any meaningful sense. Linguistically Eastern Europe was a cosmopolitan place, with the borders of the proto-nations that emerged from the medieval era mostly ignoring language until this became such a dividing line in the 19th century.

Ukraine during this time, like Poland and most of Central Europe, found its various parts passing under the control of one aspiring empire after another. There were Cossack communities in the east, Muslims of the steppe in the south, and more familiar medieval pattern communities in the west, but none pressed to dominate any other or forge an empire. In the west and more forested north Poland-Lithuania, a complex kingdom forged by a marriage between rulers, resisted Russian efforts to press westward while maintaining the delicate relationship with Crimea and the Cossack territories.

Russia expanded aggressively towards the Black Sea under Catherine, swallowing up the Caucasus region and the peoples in it. The Don Cossacks became some of the empires most potent soldiers, used to repress the non-Russian peoples Moscow found itself having to deal with. A port free of ice all year has long been a particular obsession of successive emperors in Moscow, all the way down to Putin himself, and this was when Crimea as well as the Odesa region first fell under Moscow’s yoke.

Russia’s empire didn’t stop there, obviously, grinding east to the Pacific and even the Pacific Northwest, setting up outposts from Alaska to modern-day northern California. Moscow today is obsessive about this golden age because it avoids raising questions about everything that came before - like the fact it took control of Kyiv and took its heritage as its own.

Ruled by monarchs whose ancestry typically hailed at least in part from the dynasties of the rest of Europe, the Russian Empire was always one of the most brutal. Peasants had even fewer rights there than in most places, and serfdom was abolished last of all in Muscovy. The rest of Europe saw Russia as utterly backward, and not without reason: outside Moscow and the new city of St. Petersburg a significant number of people in the country today live about as they did in Catherine’s time.

Moscow’s rule was always contested internally too, leading to waves of revolt and repression. As an empire, it sought expansion to benefit a small ruling class and no one else. Bigger than most, instead of being forced to negotiate with the peasant classes to avoid everyone starving together Moscow was usually able to weather a period of civil revolt and imperial shrinkage and bounce back.

The rise of nationalism in the 19th century posed a serious threat to Moscow because all across the empire conquered peoples began to form a coherent identity based on place and community. Russian culture, as people think of it today, was largely invented about a century and a half ago by Russian aristocrats in imitation of developments happening in the rest of Europe. During this time Russian intellectuals struggled to make sense of their empire, finally settling on pushing a narrative about it being unique thanks to its harsh climate and geographic location - a myth that other Europeans were more than happy to latch onto.

The odd blend of cynicism and authority worship in Dostoevsky’s work strangely mirrors the vapid navel-gazing of Fitzgerald, Faulkner, or Hemingway as a totem for the mentality gripping elite society in Muscovy and the US East Coast. Each is staunchly determined to feign the existence of a coherent unified culture in a country much too large for that to exist.

Russian nationalism is unlike other forms because Russia itself isn’t a nation-state. It’s an empire dedicated to asserting the dominance of Russian culture over all others in the sphere it claims. While it pretends to respect traditional rights of all groups, in the fine print you’re never allowed to see Russian is just a bit more equal than everyone else.

Ukrainian nationalism, by contrast, is almost entire place-based, imagining the country as an alliance of communities: it doesn’t, as Russia’s medieval system always has, seek to elevate specifically Orthodox values. Ukraine not only tolerates Islamic, Jewish, and even Postmodern values, but sustains a landscape where they can mix to the profit of all where Moscow’s empire seeks to assimilate or isolate them as suits its needs. Like other liberation movements that emerge to resist a colonial occupier, Ukraine’s national identity was forged in response to an invader’s repeated efforts to snuff it out.

Ukraine was not untouched by the embrace of national self-determination across the many colonized peoples of Middle Europe. And when the opportunity arose in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917, people across the territory that became independent Ukraine seized their chance. At one point Ukraine was in fact substantially larger than it is today.

The collapse of the Russian Empire followed by the withdrawal of the defeated troops of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire from large swaths of subject territory sent Europe and the Middle East into bloody turmoil as devastating in its own way as the First World War itself. Unfortunately, the newly-independent peoples of eastern Europe fought among themselves until it was too late.

In the remnants of Russia the Bolshevik movement defeated its rivals despite their receiving support from abroad. It then turned to seizing control of every corner of the Russian Empire, smashing resistance from local peoples and nations alike without mercy or remorse. Ukraine was not ready, some parts of the west controlled by anti-Polish militias and much of the Donbas region home to a unique anarchist experiment rooted in Cossack values that echoed the primeval democracy of the pre-Christian era. All fell to the Red tide which then attempted to sweep over Poland and reach Berlin, where the weak Weimar government appeared ripe for toppling.

Poland’s defeat of the advancing Red Army in the Miracle on the Vistula about a century ago was, in another of history’s ironic twists, essentially repeated by Ukraine’s defenders when the newest incarnation of Moscow’s empire tried to seize Kyiv in 2022. The USSR, soon under Stalin’s thumb, turned inward, aiming to perfect communism in the USSR before exporting it abroad.

Part of his strategy was annihilating any non-Russian peoples who dared resist. Kind of ironic, for a guy who was born in Georgia (the country, not the US state)

Whole peoples were exiled to Siberia under Stalin, but it was Ukraine that received the bulk of his immediate hate. The USSR’s breadbox and home to a massive chunk of its total population, Moscow had to keep control of a region where people spoke a language very close to Russian. If Ukraine couldn’t be managed, the Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Finns, Balts, Byelorussians, and every other subordinated group might rebel.

Stalin’s ruthless solution was the Holomodor: genocide through famine. Millions died, but Ukraine was not broken.

Anger at the brutal rule of Moscow was so extreme that many Ukrainians initially welcomed the Germans when they invaded in 1941 alongside their allies Hungary, Romania, and Finland. Today Putin’s propagandists spin this as Ukraine being full of Nazis, but the truth was that Ukrainians under Nazi occupation soon discovered that they were subhumans in the eyes of the SS. Their situation was desperate and they faced a choice of evils: Nazis who would use them as laborers and interpreters - known as Hiwis - or Soviets who had starved their relatives to death.

Many Ukrainians fought with distinction in the Soviet Army that defeated the Wehrmacht in eastern Europe - in fact, Ukrainians and Kazakhs along with the other peoples Moscow dominates have always been its best soldiers. Many Ukrainians also drove trucks for the Nazis. Some did both. That’s why it’s silly to cast accusations about what anyone’s ancestors did in the Second World War at this point (nearly all being dead) - the Eastern Front was a hell unto itself. One way or another, around a third of the Ukrainian population died during the war - that’s separate from the Holomodor.

Like the rest of eastern Europe, Ukraine’s independence was the price the Western Allies paid to have the USSR as an ally in the fight against Hitler. But Ukrainians, like the other peoples who regained their freedom in 1991 as the USSR fell apart, never forgot their desire for self-rule.

Putin’s ruscism is nothing more than a vain throwback to imaginary greatness intended to keep his people from revolting against the predation of his regime. Putin can’t tolerate Ukraine because it is a living reminder that the Russian World doesn’t exist. Nothing holds the Russian Federation together now except fear of Putin’s wrath.

Which is being buried in the fields of Ukraine each and every day. With every tank burned or drone intercepted Putin comes one step closer to his fall. The foundation of Moscow’s power has always been the perception that it cannot be resisted. Moscow sits at the center of a road and rail network that reaches every corner of the empire, allowing its rulers to dispatch combat forces anywhere in a matter of hours.

That Wagner was able to march most of the way to Moscow after seizing the absolutely vital city and supply base of Rostov-on-Don this past June was the sign the world was waiting for that the end is drawing near. All is not well inside the empire - the inability to subdue Ukraine or even seize more than a few square kilometers without suffering humiliating losses recalls every catastrophe to beset a ruler in Moscow in ages past.

And for the first time in its history, Ukraine has allies. In part thanks to the brutality of Putin’s assault, but also because so many of its citizens have gone abroad. Though the loss of population in Ukraine is painful, it is also has benefits: just as the Jewish diaspora means that there are advocates for Jewish rights in most of world, the same is starting to become true of Ukraine.

For the first time in world history it is possible to cooperate on grounds other than common nationality. Though people speak different languages, video evidence can carry vital messages anywhere almost instantly. Money likewise flows relatively freely from one place to the next.

Putin launched an old war meant for a world that is already dead and gone. While hard military power will always have its place, to use it in a way that provokes widespread outrage has starker consequences now than ever before. The means of destruction are more decentralized than they have ever been, and it is important to remember that it wasn’t the regular Ukrainian military alone that defeated Putin’s legions, but ordinary citizens who knew enough about how to fight and had the motivation to put their skills to use in creative ways.

People, as always, are the ultimate vital resource. And one of the cool things about people is that most of them want peace most of the time. That’s something that Moscow’s rulers can’t understand - so they doom themselves. Russia’s history is about to end because of their blindness, but Ukraine’s goes on.

Russia cannot exist without Ukraine. The reverse is not true. Ukraine is an actual place defined by geographic patterns that have held for thousands of years. Russia is an idea, and a rather manifestly pitiful one at that.

It’s too bad that it will take a lot more death to prove that it’s over.

There’s a lot more to the history of the conflict of course - a Ukrainian filmmaker I’m in touch with has produced an incredibly detailed documentary covering events after 1991 that you can watch on Youtube in two parts.

But for a Friday the Thirteenth post before a week off, I think it best to leave off here. Take care out there!