Battlefield Organization In The Network Age: Ukraine War Lessons

The history of warfare is a tale of adaptive human organization. One of the great challenges facing Ukraine's defenders is shedding the Soviet mentality - while fighting a war for survival.

While Ukraine’s defenders have achieved much in this war, defying expectations at every turn, there have been plenty of mistakes made along the way. I’ve often written about how most western observers keep getting their coverage of Ukraine’s fight wrong, and downplaying Ukraine’s achievements remains a preferred tactic.

But between optimism and pessimism lies the dreary realm of pragmatic realism. That’s where I live; science also calls it home. In this grey land, the 20% of Ukrainian brigades that are incredible are backed by another 20% that are solid; together these carry the remaining 40% that only get by… and then there’s the 20% which consistently under-perform, sometimes badly.

Most of the time, I focus on what works, because that is what has to be expanded and scaled up for Ukraine to secure victory. But it is absolutely true that Ukraine’s military is dealing with serious systemic challenges, some of which are not trending in the right direction - or at least not as fast as they need to. Syrskyi is slowly assembling a cadre of battle-proven senior leaders, pushing out some of the Soviet style careerist diehards - and a few who are good at putting on a good face when working with NATO partners. Yet the pace leaves a lot to be desired, even accounting for the bureaucratic inertia typical of any classically organized military.

The ongoing scandal around the 155th Mechanized Brigade is a case in point that’s receiving a lot of press coverage. Of course, there a significant part of the issue is improper expectations tied to a widespread misunderstanding about how Ukrainian brigades function. Also, multiple separate incidents taking place over a period of months are being compressed to paint a picture of a brigade that fell apart as soon as it deployed when it was probably always destined to enter the fight in separate battlegroups.

But as an excellent piece by the respected Ukrainian analyst and retired officer who writes under the moniker Tatarigami argues, the saga of the 155th is not an isolated case. With the stakes so high, the upcoming summer very likely decisive in determining the nature of world affairs for decades, Ukraine’s ongoing military reboot faces a hard deadline for demonstrating success. While the adoption of the new corps is excellent, the devil is always in the implementation.

After reviewing important developments on the fronts and before a brief outline of global developments, I’ll lay out the latest version of an ongoing project of mine that aims to develop an optimal template for organizing combined arms teams.

Weekly Overview

Both sides have chosen to mark the new year with renewed offensives. The intensifying orc assault on Pokrovsk was predictable and is so far following the most obvious routes. On the other hand, reports broke over the weekend about a major Ukrainian attack in Kursk.

Neither side is acting as if it truly expects serious negotiations to begin any time soon. Broadly speaking, my forecast for 2025 continues to see ruscist exhaustion on all but one or two fronts by summer, then an all-out Ukrainian counteroffensive - what 2023 should have been. We will see.

Northern Theater

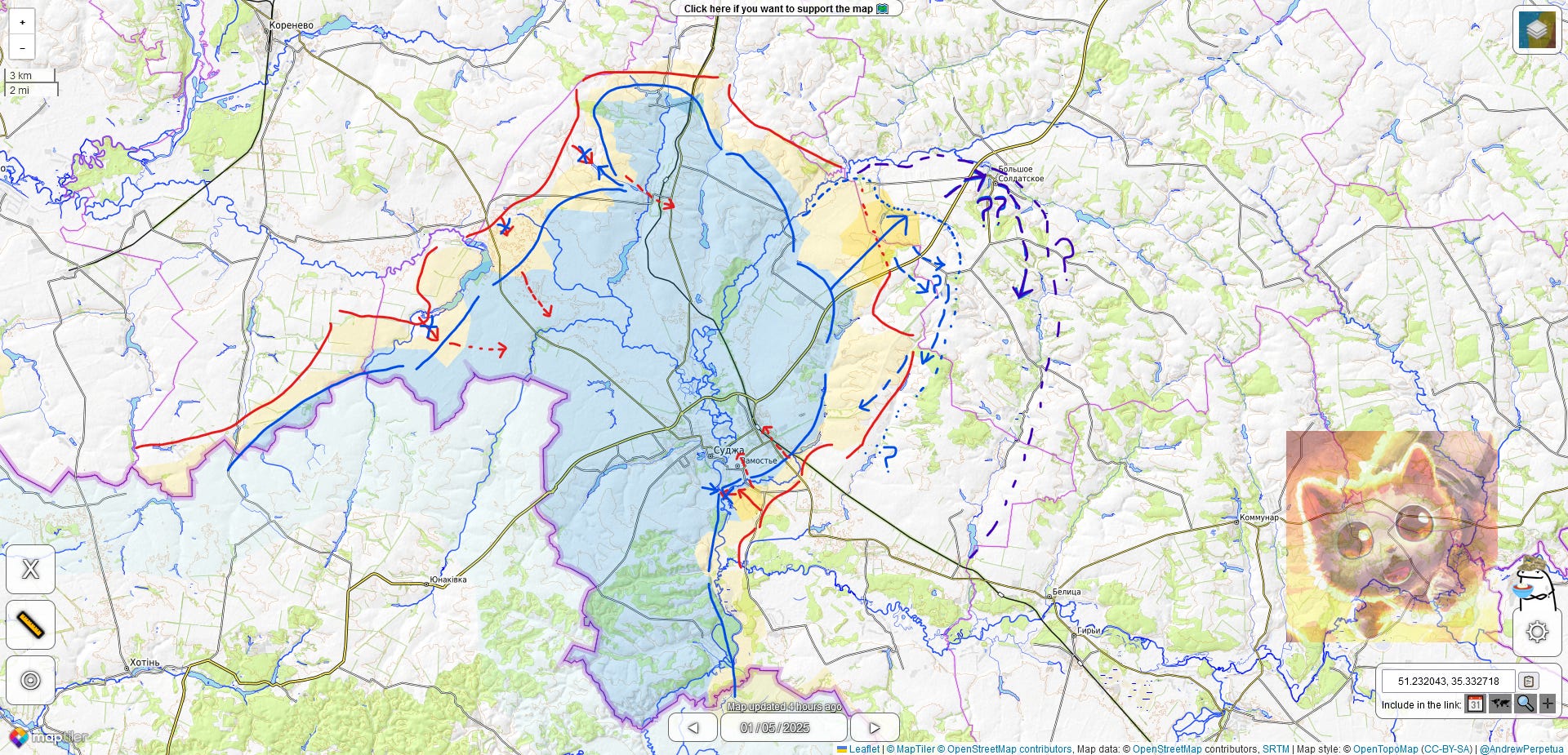

In Kursk, the fighting since the start of the new year was more or less routine until Ukrainian troops charged nearly six kilometers northeast from the perimeter around Sudzha. And that’s just what open source reports have confirmed - it’s entirely possible that this is the start of something much larger.

The deployment of a reinforced company backed by tanks and mine clearing vehicles could suggest that Ukraine is planning to expand Free Kursk to the east. At the moment, though, this and several other smaller-scale attacks reported along the perimeter suggest an opportunistic effort to improve Ukraine’s positions east of Sudzha.

South of the town, and much closer to it, orc attacks have been slowly pushing towards Makhnovka from a wooded area and Mirnyi down the rail line coming up from Belitsa. By striking towards Bol’shoe Soldatskoe, Ukrainian troops may be angling to hit the northern flank of the ruscist force pushing on Sudzha from the east. While Moscow reinforces the direct road to Kursk in response, Ukrainian troops can turn east and then south, seizing a ridge that would otherwise help the orcs advance.

There have been some references to Ukrainian attacks elsewhere in Kursk, so perhaps the effective corps Ukraine has here is plotting something more ambitious. It has always been possible, though obviously an incredibly difficult task, especially in the snow and mud, for Ukraine to use the Kursk foothold to support a broader offensive towards Belgorod. Just forcing Moscow to worry about this represents a win.

It’s very difficult at this stage to offer a forecast, given the lack of data. The footage of the Ukrainian attack so far is mostly from the orc side, and naturally attempts to play up the anticipated loss of a few of the vehicles. That along with silence from Kyiv may suggest that other Ukrainian assaults were even more successful. Or it’s a one-off. More to report in a week, I’m sure.

The Kharkiv front remains much the same, ancillary to Kursk and so mostly characterized by skirmishing along the front and periodic strikes on logistics and command infrastructure in the rear. Both Belgorod and Kursk districts are routinely struck, and lately the Ukrainians have been getting more active with HIMARS again.

Southern Theater

Jumping down to the south, where the weather isn’t quite as cold, little has changed save for a local orc push west of Orihiv that could conceivably be the start of an attempt to either reach or flank the town. It’s a regional defensive hub, so any threat to it has to be taken seriously. But Moscow has probed now and again along the eighty kilometer arc from the diminished Dnipro to Hulyaipole and nothing has come of it.

Ukraine has what amounts to a small corps guarding this front, no more than three or four mechanized and as many light infantry brigades. But 118th and 65th Mechanized as well as 108th Territorial are all reported to have or work with several drone companies plus one of the fast-growing regiments. This appears to make a big difference.

Along the length of the Dnipro skirmishing over the islands near Kherson continues, as does the orc drone safari. It’s notable that orc drone operators on other fronts will generally prioritize military targets, but in Kherson a core objective is mere terror.

Eastern Theater

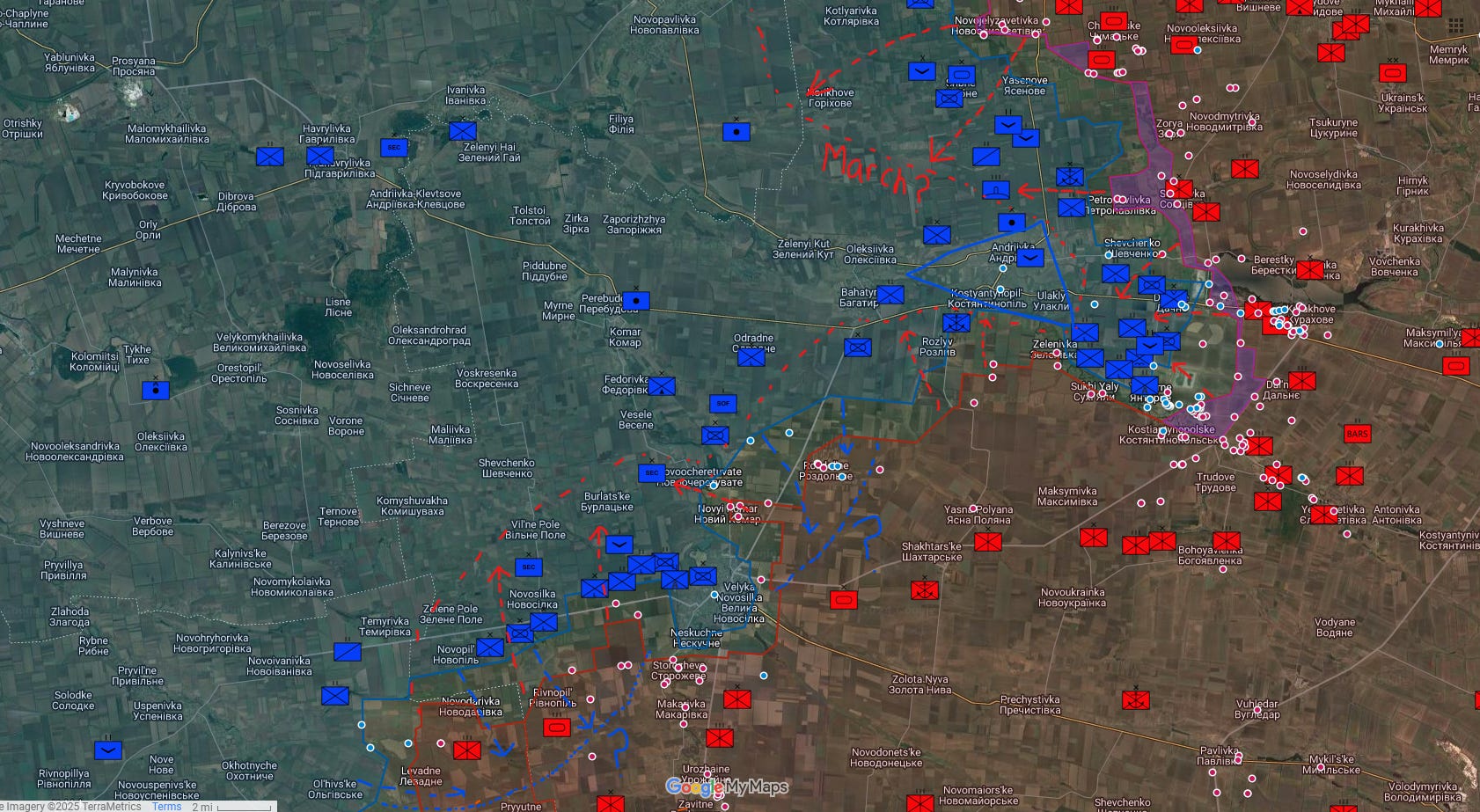

The tensest part of the fight for Ukraine is still the struggle for Donbas, particularly the Pokrovsk front. Moscow has begun the battle for Pokrovsk as predicted: striking both flanks. Since the new year the orcs have pushed a couple kilometers towards Ukrainian lines, visibly attempting to seize a viable bridgehead over the Kazenyi Torets in the north and Solona in the south. In both cases the goal is to cut the most direct logistics route connecting Kostyantynivka and Dnipro that runs through Pokrovsk.

The defense of Pokrovsk is being covered by what looks like another emerging corps with 8-10 brigades. Most are experienced, and here as in other areas the newer brigades of the 140 and 150 series appear appear to mainly serve under the command of more established formations, which seems wise.

It is to be hoped that the overburdened operational grouping that has not performed well in stopping the orc push west from Avdiivka this past year is already effectively split into corps separately handling the defense of Pokrovsk and Velyka Novosilka. The corps responsible for Pokrovsk is in the unfortunate position of having to make a hard stand, with reserves held ready to counterattack to control the flanks.

Though the Velyka Novosilka front looks bad right now, Ukraine’s defense appears to be stiffening on the southern flank near the town itself, while further north Ukrainian brigades are wisely pulling back to what are hopefully solid defensive positions in the Ulakly-Andriivka-Kostyantynopil triangle. If these haven’t been done well, there will be hell to pay, as quality control issues have consistently undermined important Ukrainian positions in the past.

Since the new year Moscow’s creeping progress towards Velyka Novosilka has been halted, though if the two major roads leading in aren’t cut they remain extremely dangerous to use. I continue to assess that a fairly substantial counterattack will be needed here on one or both flanks soon; unfortunately there are some suggestions that the orc command here might be aware of and prepared for this hazard.

Kurakhove has not technically completely fallen yet, but barring Ukraine launching a major operational level counterattack it’s gone. The Ukrainian brigades in this sector have done a heck of a job over the past couple months, but as expected are slowly falling back towards Ulakly. A grouping of 3-5 brigades should be reduced to just one or two this way, stiffening the defense of the entire defensive complex, depending on how battered they are.

However, the northern flank of this zone looks set to come under increasing pressure; so far Ukraine has not been able to thwart, only deflect, the spearhead that began creeping west from Avdiivka last spring. The line of the Vovcha, which goes from east to west in this part of Ukraine, creates a ridge that anchors any defense of the Ulakli-Kostyantynopil flank of the area. If the orcs can expand their bridgehead over the Strashnyi to the east or push south down the highway to Pokrovsk, Ukraine may be forced back yet again.

Like the loss of Velyka Novosilka, this would not be a major defeat. But there can be no denying the fragile political state of Ukraine’s defense right now. Lives aren’t worth beating a hostile narrative, but all things being equal, if Ukraine can hold the line on this front through winter that will be a sign of substantial improvement in the local command structure.

The Kostyantynivka front has been, as ever, a bloody block by block grind for the orcs. Central Toretsk is almost fully under ruscist control, however not much is now left to occupy. Ukraine is still fighting for the suburbs and outlying villages, with many useful positions left to defend between Toretsk and Kostyantynivka. This front is notably more rugged than Pokrovsk - though that’s a difficult term for someone who grew up in the Cascade range to use when referencing most of Ukraine.

Fighting in Chasiv Yar still centers on a large industrial facility at the eastern edge of the town center. Here as in Toretsk there are decent positions to the rear, but the ones Ukraine presently occupies are advantageous enough to make a hard stand the best move. I get the sense that the fighting on this front is managed by another emerging corps, as brigades have been known to move between Toretsk and Chasiv Yar - they’re only around 25km apart, the two fortresses guarding the approaches to Kostyantynopil.

To the north, the Siversk bulge is still mostly static, save for some more local Ukrainian counterattacks in places Moscow’s troops managed to push forward the past few months. While Moscow’s attacks on Kupiansk are stalled again, between Borova and Terny they continue to attempt to creep towards the Oskil. The pace remains incredibly slow, but in the Terny area it appears the orcs pushed an assault over the Zherebets river on either side of a large reservoir. Ukrainian troops are presently hitting it hard: it remains to be seen whether the orcs there hold on or it falls back into the gray zone.

Overall, the fighting on the ground remains intense, but Moscow’s efforts continue to slowly weaken in non-priority areas. The overall pattern continues to suggest an effectively franchised operation, each front competing with the others for resources with officers mounting fruitless attacks mostly to prove they’re working. Only in the Pokrovsk area do they show any sign of understanding that their ultimate target is not any particular place, but Ukraine’s military power overall.

That they have been working against a Ukrainian command that, in this area, really does appear to have broken down on numerous occasions without much excuse. It’s troubles in 2024 have been latched onto by the foreign media, giving the false impression that the situation is identical everywhere.

It’s always amusing to read commentators accuse Syrskyi of micromanaging Ukraine’s fight when most of his interventions target senior leaders who have visibly failed. Reports that he specifically ordered 79th Air Assault to evacuate Uspenivka suggests that someone in charge more locally was not responding to the information being passed on by frontline teams. No one should ever need permission to retreat: if the situation calls for it, pull back. This is area warfare. The alternative is a bloody mess with little gain.

Air, Sea, & Strike

Ukraine seems to have hit a new normal with respect to the strike campaign, with regular drone waves testing and stretching orc air defenses while causing some mayhem, opening the door for bigger hits with precision missiles. Moscow attempts the same drill, but with more limited success thanks to Ukraine steadily building up its air defenses - though not enough. With 3,000 small cruise missile drone hybrids and 10,000 long-range drones scheduled for delivery in 2025, Ukraine should be able to expend hundreds of each on a monthly basis while retaining the capability to launch some truly overwhelming strikes.

Moscow, unfortunately, has been able to increase its own missile stockpiles despite sanctions. But if global Patriot interceptor production keeps pace, as it should be able to, in a relative sense Moscow will soon find itself trapped in an unpleasant situation of effective parity, at best, when it comes to strategic strikes. If Ukraine can use a significant fraction of its new assets on operational level attacks to interrupt supplies flowing to a particular front, the effects could be spectacular by summer.

The aerial fight is also trending Ukraine’s direction, if slowly. The first Mirage 2000 jets have arrived, with around ten planned by summer, and they ought to allow Ukraine to conduct opportunistic raids on high value targets. Having to rely on improvised mechanisms that need substantial pre-flight programming work limits how quickly Ukraine can respond to intelligence. But a Mirage on patrol carrying even a single Storm Shadow can be tasked in flight to take advantage of a chance to slip a weapon literally under the enemy radar to knock out a meeting of commanders.

If, by summer, Ukraine does not operate at least a half dozen Gripen jets with their Meteor missiles that can outrange anything launched by orc jets, then Europe truly is so dependent on the US that it had better to whatever Trump says. Assuming that Swedish AWACS aircraft are on patrol by then, as they should be, Ukraine would gain the ability to seize control of the skies for at least a limited time whenever it chose.

Also, Moscow still hasn’t managed to kill a Viper yet, yet every time the ruscist missile waves come, Vipers are up there knocking down incoming and saving lives. One has to wonder if the best possible advanced training for a newly qualified combat pilot once they have basic competence flying the F-16 isn’t simply hunting Shaheds and Kalibrs in western Ukraine.

At sea, Moscow’s days as a power in the Black Sea look to be over. Surface to air missiles fired by naval drones got not just one, but two orc helicopters the other week, negating the most effective means of hunting Ukraine’s nifty innovation. Eventually someone will work out how to strap some passive and active sonar buoys to one and a torpedo to another, with a third acting as signal repeater to form an anti-submarine hunter-killer flotilla. A submerging drone carrying a few small cruise missile drone hybrids could deliver some nasty surprises ashore.

When you disaggregate function and form, great things are possible. As it turns out, you don’t always need ever more expensive custom technology when lots of simply adequate gear will do.

Yet putting all the essential ingredients together is never a simple task. And that is proving one of Ukraine’s most significant challenges. Rectifying this is of extreme importance, and time is short.

Bottom-Up Military Organization In The Network Age

I have a strong background in two fairly distinct academic worlds: science and policy. The latter is actually the older thread of my work, where I hold formal credentials and even scored a peer-reviewed publication in a fairly prestigious journal with an excellent co-author based on research done for a masters in public policy under her guidance.

As a doctoral dropout I benefit from PhD-level training in geographic and environmental science. A great deal of my research has always been geared towards bridging the policy and science communities, and I’m moving in that direction with my professional writing too.

I’ve long been fascinated by the age-old puzzle of how to best combine the different ingredients of combat power in any given era. As drones radically alter the landscape every soldier now inhabits, in much the same way that machine guns and before those gunpowder did, the best way to manage personnel and equipment will too.

I also happen to know what it’s like to train in a combat arms specialty where hiding is the better part of survival, and the other half is firepower called down by radio link. So in the science portion of this week’s post, I’ll outline the latest version of my ongoing effort to design an organizational structure and general doctrine suitable for the battlefield in Ukraine as the new corps structure evolves.

It’s worth beginning by summarizing Tatarigami’s excellent analysis of why Ukraine is having trouble managing its assets:

New brigades keep being added while veteran formations lack replacements.

Many officers give false reports to cover up loss of positions and order teams to hold places without proper support.

Inadequate training for mobilized soldiers as well as junior leaders.

Overwhelmed command structure thanks to the reliance on ad-hoc operational groupings and lack of traditional corps-division structure.

Mobilization failures are starving Ukraine’s ground forces of infantry and allowing people with means to evade conscription.

Hyped expectations about what Ukrainian forces can hope to actually achieve on the ground.

Every one of these points is valid - I’ll focus most on the fourth in this section. As to the others, while I recognize the need to add brigades to this point, Ukraine should now have enough to focus on boosting the veteran outfits. The second issue will hopefully be addressed in part by the use of digital reporting apps - if implemented correctly. Better training is one of those ongoing quests that needs its own full post. And fairness in mobilization is obviously huge, with the lack of clear end of service terms likely a major impediment to voluntary recruitment.

If someone has been fighting this war for more than three years, they almost certainly need a break. It’s time to make them trainers. Exposure to the front should be seen like exposure to radiation. Exceeding lifetime limits must be voluntary. However, lowering the mobilization age is not the solution. If the system is working well, there will be volunteers. They will come when there are enough modern weapons and quality leadership, plus guarantees with respect to terms of service.

While I have the utmost respect for Tatarigami’s work, I do feel an obligation to identify a slight western bias in it. This is not a criticism, only a statement of where the rhetoric he (I’m assuming he, sorry if that’s wrong) uses positions his case along the spectrum of domestic Ukrainian politics. That impacts both his framing of the problems and solutions - not a problem, just a reminder.

The recommendation that Syrskyi be replaced because he’s too Soviet, despite Syrskyi being responsible for promoting officers like Drapatyi, who Tatarigami actively praises, is a likely. Another is the assumption that a classical NATO-style corps-division structure is an automatic remedy for Ukraine’s organizational ills.

Most of the attacks on Syrskyi do not seem to consider the limits someone in his position is facing. He’s up against serious inertia, much of it caused by his predecessor’s decisions. Zaluzhnyi almost never sacked entire brigade commands; he reportedly became angry whenever Zelensky’s office tried to get a handle on what was actually happening at the front. It was under him that western equipment was concentrated in new brigades.

Syrskyi should be up for ruthless and constant critique. But someone in his position should be judged mainly by who they promote and fire. The mythos of the all-powerful general (or CEO) is one of the more self-defeating aspects of the postmodern delusion. All these people do is yank on a few levers of indirect control in the hope that translates to effective action at the ground level.

I don’t know whether Syrskyi is a good leader or not. All I can say is that Ukraine is killing orcs at twice the rate it was under Zaluzhnyi and taking no additional losses. If someone can prove this is a lie, I’ll re-evaluate. And in warfare, a shift like that is a substantial win. Of course for the most part the success is down to small drones, which have been funded and produced as much by grassroots initiatives as the central government in Kyiv.

As far as the corps/division side of the critique goes, here I feel a need to once more caution against blindly following the Second World War model. That’s what the orcs have been doing since 2023, and casualty rates are spiking in exchange for exceptionally weak gains.

I am not saying that those advocating this approach are entirely wrong, I just expect that the effects won’t be quite as they imagine. Directly porting a system of organization built under a certain set of assumptions often proves dangerous in the world of policy.

Simply standing up a bunch of corps and organizing Ukraine’s many brigades and separate regiments and battalions into divisions underneath them solves nothing in and of itself. You can achieve the same effect without needless duplication of functions by making divisions informal, basically staff divisions that allow a corps-level commander to delegate most direct management tasks and focus on high level stuff.

There are solid scientific reasons why any military organization is shaped like a pyramid. Geography and constraints on the availability of certain resources make it so. I doubt very much that there will ever be an effective human organization that doesn’t have some form of vertical responsibility chain where one level manages multiple subordinate pieces and is in turn so managed. This can be extremely efficient, provided that everyone knows their role.

Nothing says that a senior-subordinate relationship has to involve a social power dynamic. It’s sole functional purpose is to ensure that information and resources flow where they need to go as smoothly as possible. The number of subordinate elements each level of the pyramid has to keep in touch with is limited by the human inability to mentally track more than about 5-6 components in a group without needing to create sub-groupings to avoid overwhelm. The number goes down as stress rises.

Over history, military organization pyramids slowly became bigger in every dimension, a warband led by a chief personally bound to a group of lesser chiefs transforming into the complex Napoleonic system that is still largely used today. The specific chain: individual-team-squad-platoon-company-battalion-brigade-division-corps is often held as sacrosanct, but it evolved from earlier forms of military organization. The Napoleonic model, especially the variant which places three elements at every level in a telescoping triangle, is aesthetically attractive but shouldn't be idealized.

At the heart of the thing is a need to balance the amount of subordinate elements each level of command can handle with the requirement for essential capabilities to be where they are required at all times. All warfare has always been combined arms warfare, with each ingredient contributing something irreplaceable. When that ceases to be true of a given thing, it disappears. But while form changes, function remains largely constant. Like organisms in an ecosystem, military forces must adapt under selection pressures or fade away.

A lot of military professionals, both foreign and Ukrainian, are under the misapprehension that simply reorganizing Ukraine's brigades to fall under the authority of divisions which are commanded by corps will work. That’s essentially what the Muscovites tried to do after 2022 using Soviet doctrine as a model, and the net result has been an even more inefficient, if sometimes marginally more successful, organism.

A fair few analysts appear to be under the impression that simply filling out a proper org chart will bring the desired results or compensate for the systemic issues undermining Ukraine's fight. I'm not saying that a formal division-corps system is necessarily bad, but it or anything like it has to be developed organically by expanding existing proven formations. This will mean that proven leaders within brigades like 47th Mechanized, Third Assault, 93rd Mechanized, Magyar's Birds, and a couple dozen others will wind up being given a lot more responsibility. Not all will understand right away how to cope with the higher level of complexity. There will be growing pains.

What I'll lay out now is a general template for understanding military organization in the Network Age from the bottom up. I already suspect that an approach like this is emerging in Ukraine's most effective brigades and will eventually be extended to form the new corps with divisions maintained as informal internal groupings.

The objective of this system is to ensure that resources of limited availability are managed by higher echelons which can allocate support as the situation demands. Line teams will be able to call on whatever they need, with the time to arrival determining whether they hold a position or evacuate.

The ability to advance into the grey zone and eventually enemy territory will be predicated on having enough firepower to direct at hostile positions that isolated orc detachments can’t even fight back. Slowly expanding this zone of domination is the key to offensives that won’t bleed Ukraine dry. Drones will play a major role, but the conditions front line teams face are critical.

Maintaining a front boils down to being able to apply firepower when and where it is needed to prevent the enemy from advancing. This task has not fundamentally changed in thousands of years, but technology dramatically impacts the nitty-gritty details that ordinary soldiers have to cope with. Since machine guns were first widely fielded over a century ago, the front has usually been defined by the arcs of fire covered by MG teams.

Whether part of a team of three or thirteen, the machine gunner scores the vast majority of kills. Rifles and carbines are for individual self-defense and covering fire that pins the enemy down until the MG has time to wipe them out. Armored vehicles were first used in large numbers to mitigate the vulnerability of waves of flesh to a relatively small number of machine gun positions. During the First World War, the German Western Front from 1915 through 1917 depended on layers of fortified positions anchored by machine gun nests. Allied charges backed by intensive artillery barrages always discovered that enough German nests had survived to slow an advance. This gave the Germans time to bring in reserves, mooting the impact of any attack.

Armored vehicles allow attacking infantry to come close enough to a machine gun nest that small arms hitting it from multiple angles overwhelms the defenders. That's why mechanized tactics were so devastating in the Second World War, but the era of tanks racing across the battlefield unimpeded didn't last long. First infantry teams incorporated large numbers of light artillery pieces as anti-tank guns, and by 1944 the use of shoulder-fired weapons like the American Bazooka was commonplace.

By the end of the Second World War, combat was once again resembling the First World War most of the time, the explosive victories on both of the Nazi Empire's embattled fronts coming only once the Allies or Soviets had already defeated the majority of hostile troops in a broad area by systematically annihilating the front. This entailed all the machine gun teams and supporting elements backing them being targeted and either wiped or overwhelmed.

The situation in Ukraine is the same, only now drones have become an integral supporting element capable of providing prompt precision fire support. Their accuracy and portability makes them both potent and difficult to suppress, and their ubiquity means that the single best tactic for neutralizing an enemy team along the front - catching them by surprise - is incredibly difficult.

Victory at broader scales emerges from countless smaller victories at the local level, most of them so routine that they're taken for granted. They happen when the people in contact with the enemy have all the tools and resources they need to repel an attack - advancing is merely moving to a new defensive position closer to the enemy’s rear. Because the enemy can bring a whole array of different resources to bear, it is essential that front line teams have support from and remain in perpetual contact with support elements usually located behind the front and whose own security depends on the front staying intact.

Why can't these all be under the direct control of someone physically on the front line? Because there's only so much any team, including whoever is in charge of organizing and directing it, can keep track of. That's why the most basic element of an army is the fire team, either a trio or two pairs who live, train, and fight together. This grouping is small enough for each member to feel a close bond with all the others, allowing them to act as a single organism in the field. At higher levels, bonds between officers matter - but combat teams care only about who is adjacent to them.

Such a small grouping can only carry so much gear. A single machine gun, spare ammo, radio and electronic warfare gear, and a rocket launcher pretty much maxes it out. Still, that gives the team the ability effectively engage targets out to a kilometer or so on flat ground. A pair of orc BMPs emerging from a tree line can be knocked out and the troops on board pinned down in a matter of minutes if the team is alerted by a friendly drone.

Of course, any team can be overwhelmed, especially if the enemy comes from two directions. That's why fire teams, like individuals, don't fight alone. Two or three are permanently attached together in a squad usually led by the most experienced soldier. A pair working together can continuously monitor both sides of a tree line, as one example, and if one closer to the enemy comes under too much pressure it can withdraw covered by the other.

In Ukraine, a single squad is often split across several fighting positions in a single tree line. Fire teams of six now appear optimal because this gives the team leader the flexibility to break into three pairs, two groups of three, or a NATO-standard fire team of four plus a support section. This number of soldiers can also fit into nearly any troop carrier, of which each team is assigned one - ideally a true armored personnel carrier, but often a mine-resistant truck will have to do.

Each team of six is assigned - in addition to every soldier’s personal weapon, grenades, and other kit - a machine gun, anti-tank rocket launcher, radio and electronic warfare pack, spare ammunition, and a couple shotguns for last-ditch drone protection and trench clearing. That allows the team to defeat enemy infantry teams and light vehicles on their own out to a distance of a kilometer while keeping it light enough to hike a couple kilometers if necessary.

Each team maintains at least one entrenched fighting position they’re always improving and another alternate (at least one), plus a rally point for when retreats happen in a hurry. It is also part of a larger squad with ten or so members, the other four operating the squad’s armored vehicle and maintaining supply caches. This ensures that the squad has the ability to replace casualties on the line team and conduct small internal rotations.

Two squads come together to form a platoon, which is the basic tactical level fighting unit, able to seal off two tree lines and the field between against anything less than a company-level assault. They are the essential membrane that defines the front line, and even in an age where drones do most of the fighting combat teams with direct fire capabilities will always be needed as the final layer of security.

But even the ability to swiftly knock out several enemy armored vehicles and pin down accompanying infantry isn’t enough to stop a sufficiently reckless foe. Better but more scarce tools are required, and it isn’t sensible to expect every team on the front line to carry everything they could possibly need. You form an army to take advantage of other teams with specialist tools. In the modern world, their coverage area usually extends quite far, allowing one to back several others unless the enemy hits with overwhelming force.

Four platoons come together to form the front line element of a standard line company. A fifth platoon of two or maybe even three squads, which I’ll call the heavy platoon, operates weapons that have a longer range and heavier punch: ATGMs like Stugna and Javelin, MANPADS like Stinger and Igla, and 40mm or 30mm grenade machine guns. In general, the troop carriers this platoon rides to battle should be IFVs of the Bradley, Marder, or CV-90 type, able to offer intensive fire support.

In an attack that breaches the drones patrolling the gray zone and seriously threatens positions in the company’s area of responsibility, the heavy platoon can pour a heavy dose of firepower on advancing hostiles to allow vulnerable teams to retreat. The heavy platoon can also support or even lead local counterattacks to reclaim positions.

A single company outfitted like this should be able to defend a two kilometer stretch of front two kilometers deep and screen up to five in less dangerous areas. It ought to be able to knock out 4-8 enemy vehicles and the soldiers with them even if lacking other support.

Four of these line companies will constitute the primary force of a reinforced battalion backed by supporting elements. However, rather than deploying on a line, they’ll create a box over a front spanning around 5km, 5km-10km deep. This allows for company rotations every few days, platoons slowly exchanging positions, to let half the force enjoy a lower alert level for half of the time. Battlegroups on the front should plan to swap out all their companies every two weeks.

The line companies in the battlegroup will be supported by a heavy company. It will have two tank and two mortar platoons, plus a command platoon to coordinate their employment and a medical platoon to move casualties to evacuation points. With four tanks and eight mortars, this company is allocated on an as-needed basis to back one or both forward line companies. Able to respond to a threat in a matter of minutes, mortars are excellent for breaking up infantry attacks and nothing that rolls on wheels or tracks enjoys encountering a tank. These are especially useful in supporting attacks into enemy held territory.

The five combat companies can also be joined by a sixth as needed, generally an ad-hoc group including combat engineers or other specialists required for a major operation. But the greater part of their support comes from half a dozen support companies, each with its own specialty, that allocates platoons to back up line companies.

Drone companies maintain one recon, 3-4 strike, and a fighter platoon each.

Fires companies field four platoons each with a pair of field guns, likely mobile 122mm Soviet-era pieces or towed 105mm howitzers, plus light rocket launchers.

Engineer companies handle construction and demolition of fortifications, including minefields.

Medical companies establish a field hospital that serve the casualty evacuation points. Patients are stabilized then transported to the rear.

Supply companies help maintain the network of supply dumps battlegroup elements require to keep fighting and coordinate salvage of damaged vehicles.

Headquarters companies handle intelligence, coordination, and other high-level services.

Ukraine has generally used reinforced battlegroups as opposed to coherent brigades from early in the war. Each brigade is constantly working to keep two or maybe three battlegroups in the field, with battalions from the territorial guard often taking the place of ones from mechanized troops, simply re-flagged as members of the brigade. The point of common standards and training is to make sure that this can happen smoothly, because it’s pretty much inevitable.

While organizational pyramids can and generally should be flattened across the board because of the way technology can improve and structure information flows, the shape isn’t going away, because it oddly enables flexibility. And there can be no doubt that Ukraine needs far more of that at higher echelons which the emerging corps structure should introduce into the fight.

Instead of a formal NATO-style corps/division structure, which will take a long time to implement, I suggest a hybrid approach that creates about twelve corps, each assigned 8-12 line brigades and several supporting brigades. These will continue to be administrative shells that contribute two active battlegroups to the corps with a third resting and refitting.

The corps level is where intensive support like air, HIMARS, and 155mm artillery strikes, field repair of damaged equipment, and the logistics required for major offensive operations gets managed. Each corps assigned a section of front between 80km and 120km to support, deploying between one and two dozen brigades to handle the assigned sector. Each corps will assist brigades with training and supply and enabling active battlegroups as they seek to control their own areas of responsibility.

Eighteen battlegroups in a corps plus numerous supporting elements is too many for a single staff to actively manage, so that’s where you create informal divisions - five to six in total. Three will handle 4-6 deployed battlegroups each, resolving command conflicts and allocating scarce resources as the overall situation demands. A leading staff officer supporting each of these division groupings will report to the corps commander.

By keeping the division echelon “in house” like this, the danger of creating a useless layer of command is mitigated. The corps commander is advised by a council of staff officers, chief among them acting as a sort of shadow commander who mostly deals with rear area matters while the corps commander oversees the front, where command presence is more likely required. A corps commander assigns battlegroup commanders areas of responsibility, and they handle the companies under their purview accordingly.

To get there, put solid brigade staffs at the heart of each corps, and organize the other brigades around them. The challenge is to preserve the vital connections between existing brigade and battlegroup leaders that are working well while finding ways to replicate them. Here I have great hope that if Ukraine’s digital apps are rolled out right, data will show the way.

Alright, that’s clearly only scratching the surface - running a bit low on time to cover more this week - but I hope it sparks some thought and discussion among those the ideas can help. I’m still working on ways to diagram this out in a presentable way - more to come in the future. Now, to the dismal world of politics once more.

Geopolitical Brief

Ukraine-USA

It would be much easier to convince Ukrainians under the age of 25 to voluntarily join up without expanding the draft as Jake Sullivan wants if the Biden Administration had at any point this past year flooded Ukraine with armored vehicles. But the powers-that-be among Team Blue’s oh-so-brilliant leaders appear to have decided that the risk of Ukraine winning under Trump outweighs any benefit to be gained from trying to arm Ukraine fully before Trump takes office.

There continues to be talk of hundreds of armored vehicles, but unless the number of hundreds hits at least two dozen in the next two weeks I have to assess that Team Biden has decided to sell out Ukraine one last time. Watching partisan Democrats sit back and console themselves over blowing another winnable election by talking quietly about how Trump is sure to hang himself is just rich. Resisting fascism by waiting it out is very on brand for a standard-grade postmodern American social justice cosplaying liberal.

But democracy and the Constitution are just words to Vichy Democrats, their definitions whatever the high priests on TV insist is true this season. Weird how that was Team Red’s deal about twenty years ago. Anyway, rumor mill has it that Putin gave Trump’s negotiating team the middle finger, which if true is pretty much what I figured would happen if the orcs couldn’t reclaim Kursk by Trump’s inauguration.

Very, very difficult to see practical grounds for a stable ceasefire now. Which leaves victory the best option for everybody. But will team Trump correctly perceive its own self-interest?

Ukraine-Europe

Europe continues to muddle its way towards a situation where the members of NATO and the EU that feel the most concerned about Moscow drive policy for the continent. That’s not a bad thing, and there is reason to hope that the Ramstein protocol - which includes the Pacific democracies - will evolve into a permanent mechanism to contain russia.

Depending on how the next few years go in the USA, some states might want to join too. As far as I’m concerned, Trump’s proposed tariffs are a form of economic warfare waged against the West and East Coasts. Guess nobody told Florida they’re part of the latter, too. A former European leader recently remarked that Europe can no longer base its security on the whims of voters in the American Rust Belt. I know the feeling - and I grew up in the part of California the rest of the state up and forgot.

Middle East

While the Hezbollah-Israel ceasefire is holding and Syria is staying quiet, Moscow pulling forces out as quickly as it can, Gaza is still a charnel house, courtesy of Israel. It’s the Iran front that may get interesting in a hurry. Reportedly, Jake Sullivan is pressing for Biden to take advantage of what Sullivan’s Mossad buddies are insisting is a unique moment of vulnerability for Iran because of Israeli air attacks.

This is probably just him angling for a future job, posing as a big Iran hawk because that’s the way he scents the wind shifting. But it’s always concerning when Americans casually talk about bombing Iran’s nuclear program as if the crown jewel of the mullah regime being knocked out wouldn’t trigger a broader war. Gotta love those Ivy League experts who have never been in uniform but see American military might as invincible - unless Putin is involved, in which case run for the hills in fear of nuclear annihilation.

But something approaching a bipartisan consensus is slowly emerging that the US needs to bomb Iran’s nuclear sites. If that happens, and American personnel are killed in the blowback, I hope every single American leader who let the stupidity go forward meets a killer drone, real soon. Since it costs just a few thousand dollars for a successful strike in Ukraine, it might be just about time to crowdsource assassination campaigns against any twit who decides to play Napoleon. Hitler and Stalin and Putin are bad enough.

Pacific

Not much new to report, happily. South Korea’s political drama continues, but that’s democracy. Japan is edging towards acting like a normal world power again, but very politely. Most players are waiting to see what nutty stuff Trump does. Like bomb Iran. With luck, all he’ll do is impose effective taxes in the form of tariffs on ordinary Americans.

Concluding Comments

As far as hyping what Ukraine can accomplish goes, while I know that I often make maps showing bold Ukrainian moves, I hope it comes across that these are forecasts of what could happen provided certain assumptions hold. I try to be clear about these, but in trying to put these posts together over the course of about 8-10 working hours I know I at times fail.

Though I write often about Ukraine’s victory, my standing argument has always been that its territories will return in negotiations after a sufficiently large military success. A violent reconquest of urban Donbas and Sevastopol has never, ever been in the cards.

But everything that has happened over the past three years suggests that Ukraine doesn’t need that. Putin has staked everything on a stupid war fought for the worst possible reasons. And the damage he’s doing to his own empire will prove fatal: in truth, he’s launched a crusade against the idea of a Europe free from Moscow’s domination. Perceiving D.C. to be uniquely weak, he won’t stop pushing until someone makes him. Give Ukrainians the resources, and they’ll do that before NATO or the Ramstein group has to.