Predicting The Next Russian Offensive

An evaluation of Russia's winter campaign options in Ukraine

As I have been arguing for several months, a major new Russian offensive against Ukraine is clearly planned for this winter.

I am in the process of switching most of my scientific analysis of the Ukraine War to Substack, but several recent pieces are still getting traction so I’m leaving them there for now. But for reference, here are some “Friend” links that will let anyone read them without running up against Medium’s free article limit.

Putin’s New Plot To Destroy Ukraine

To save you time, here are some highlights:

In September, Russia’s military efforts in Ukraine began to systematically change. Ukraine’s successful liberation of Kupiansk and Izium proved that Russia had too few troops on the ground to even take Donbas. Attempts to encircle Ukraine’s main forces in the region were ongoing from February and came dangerously close to success, but this effort was defeated utterly by the loss of an equipment reserve in Izium Russia had been building up for a major advance behind Ukraine’s main lines.

In October, November, December, and January Russia’s leaders openly embraced national mobilization, a skewed memory of the Second World War, and the idea of an existential confrontation with NATO. This was accompanied by nuclear saber rattling, changes to domestic law surrounding soldiers’ rights, and a campaign of terror against Ukraine’s electric, power, and heating infrastructure as well as a dedicated PR push abroad that aimed to cast Russia as an anti-colonial power fighting a righteous war.

Russia has used these four months to reboot its military, abandoning new doctrines developed in recent years to take advantage of a supposedly more professional force. Instead of battalion-sized combined arms groups, Russian forces are now deploying in more traditional divisions and brigades in the old Soviet style. They have also made extensive use of Wagner mercenaries in places like Bakhmut to give Russian regulars a break from offensive operations.

Russian offensive efforts in and around Bakhmut have primarily been intended to hold down and deplete Ukrainian forces, preventing them from launching offensives elsewhere. The heavy use of Wagner troops backed by artillery allows Russia to fill a personnel gap and dispose of people it sees as a net cost to society while giving the army time to recuperate and train hundreds of thousands of draftees.

A new major Russian offensive is set to begin in February - it might have already started by the end of January, as Ukraine’s President recently suggested - to give Putin some kind of victory to mark the one-year anniversary of the failed assault on Kyiv. This attack needs to start before the danger of the spring mud makes large-scale movements extremely difficult, giving substantial advantages to dug in infantry backed by artillery.

Given that complex military operations have an astounding number of moving parts, they are usually planned well in advance. False signals are sent wherever possible to cover plans until it is too late for the other side to effectively respond.

All success in warfare boils down to placing sufficient combat power and then using it effectively to secure control of vital locations. Combatants try to create asymmetries they can exploit to their advantage, and these can be produced through technology, numbers, or surprise.

Whatever works is the fundamental law of combat, and the desire to survive keeps combatants constantly innovating to stay alive.

Analysts who insist that Russia is on its last military legs are making a terrible mistake. The history of warfare shows that when a power is desperate enough, it often summons hidden reserves. Germany in the Second World War did this multiple times, as did the Soviet Union when it faced the Nazi onslaught.

Russia’s military has been shown to have extreme weaknesses, particularly in the realm of personnel. To achieve surprise, Putin sent his forces into Ukraine almost totally unprepared to deal with substantial opposition.

He then failed to promptly withdraw forces from the Kyiv front when the bum rush on the seat of Ukraine’s government had failed. Instead of a week of fighting followed by a redeployment to the south or east, where Russian forces were still taking ground, Russian forces spent a month trying in vain to surround Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, and Kharkiv, burning through troops who had not been trained for the intense warfare they found themselves in.

Russia’s critical weakness throughout 2022 was an inability to restore its front line units’ fighting strength in time to take advantage of Ukraine’s vulnerabilities. Forced to fight a slow retreat from the February 23 line of contact in Luhansk and the Azov coast, Ukraine’s own military largely burned through the soldiers deployed on the front lines last winter, suffering atrocious casualties.

But Russia was not able to legally deploy conscripts, who make up a huge proportion of its military strength, unless they signed contracts. And even if they did, Russian law allowed soldiers to refuse to fight in Ukraine without legal penalty because it’s a foreign country

Moscow tried recruitment drives and bullying soldiers into signing contracts for more than six months, but the shocking defeat in Kharkiv, right next to the Russian border and a major military deployment area, made it impossible to pretend Russia could continue on like it was. So Putin took the dangerous and unpopular step of announcing partial mobilization to give his generals the bodies they needed to hold the line as well as build up a new force to go on the offensive in a few months.

Russia also announced the annexation of four Ukrainian border regions its forces had partially occupied in order to prevent soldiers from refusing to fight in Ukraine. By making them legally Russia, Putin was able to not only force troops to serve but also credibly threaten nuclear retaliation if Ukraine tried to press its offensives too far.

Many NATO leaders, particularly the US President, appeared to take the Russian shift to a mostly defensive stance starting in September as a chance to renew ceasefire negotiations. Using the threat of nuclear war as a stick and a feigned desire for peace as carrot, likely a big part of the reason he did an about face and allowed the units stuck across the Dnipro near Kherson to pull back, Putin managed to delay an increase in the flow of military aid to Ukraine.

He couldn’t leave Ukraine alone, of course, as this would upset the hardliners Putin now depends on entirely to remain in power. So the missile and drone campaign against Ukraine’s infrastructure began, in part to punish Kyiv visibly but also to spread out and deplete its air defenses.

Russia’s objective is now clear: it has been preparing the way for a major ground attack before the end of winter. Putin is trying to leverage a narrow window where Ukraine’s air defenses are spread out and depleted and its tanks are starting to run out of Soviet-era ammunition to make gains before the weight of Ukraine’s new and more modern military gear can be brought to bear this summer.

After making this case for several months, it is grimly ironic to see think tanks like the Institute for the Study of War and even the Biden Administration come around to the same hard conclusion I did last year: Russia’s war on Ukraine will go on until one side or the other is exhausted and collapses.

A nuclear escalation is increasingly likely in the coming year. Where I thought 2022 had a 50-50 chance of seeing at least one nuclear detonation, I suspect 2023 the odds are more like 60-40, possibly a bit worse.

For Ukraine to survive, it has to defeat Russia’s next offensive then counterattack to liberate the lands Moscow is trying to steal. Once Putin’s military is pushed to the brink of failure, the moment of decision will come.

Until then, Ukraine faces the challenge of figuring out where Putin’s new forces will enter the battle. Conventional wisdom holds that they will intensify the attacks in Donbas, perhaps hitting the northern end of Ukraine’s line in Luhansk.

Some still believe a threat to Kyiv from Belarus will emerge. And a few others, myself included, believe that Putin will likely open a new front entirely.

Russia’s attack on southern Ukraine went almost exactly as I expected it would before the outbreak of major fighting last February. The reason I was able to work out what Russia wanted to do is that I’ve developed an effective systems approach to military operations that focuses on the interplay between logistics, capabilities, and terrain.

Paid subscribers to this newsletter will eventually get all the details and even some models I intend to test in a wargame at some point, but for now, a heuristic approach will serve.

In short, geography is the true god of war. To put military units with enough combat power to win a fight anywhere on the map requires both getting them there and keeping them supplied. Transportation routes are the major limiting factor in modern military operations, along with the ability of your enemy to stop you from accomplishing anything you desire.

Major ground offensives covering more than few dozen kilometers of area in terms of frontage or depth of attack depend on railroads. And if you want to move more than one or two kilometers on a modern battlefield, you generally need roads.

Where there is complex terrain along a given transportation network, places like river crossings or towns, there you have to expect some kind of defense. Clearing it takes time and makes your forces vulnerable, so minimizing the number of ambush spots along a route of advance is ideal for both individual teams as well as entire armies.

Ukraine’s ferocious defense has proven that it is generally easier to hold ground in modern warfare than it is to take it against determined opposition. Whenever you commit to attacking a place, you reveal your intentions to your opponent and also create a logistical trail they can attack. Combat is all about tradeoffs, and everything has a vulnerability, which is why more and more forces are using units that mix stuff like tanks and infantry, which were traditionally organized separately.

On the modern battlefield, information is cheap. Drones and remote cameras can scour the landscape, and eventually AI will help spotters pick out camouflaged targets. The ubiquity of precision weapons means that what is seen can usually be killed, often very quickly.

Modern military operations at the local level are about moving fast between hides, inflicting damage and running away to avoid receiving any in return. To do this right requires small teams of troops with high morale and flat command structures that can swiftly adapt to changing conditions, not the rigid planned hierarchies of the Soviet - or even standard American, in truth - model.

At broader scales, bigger units more or less act the same as smaller ones. There is a tradeoff, though, between size and detectability, just as there is another between size and ability to sustain offensive operations.

All of this means that a properly equipped defending force can inflict horrendous losses on an attacker, even if outnumbered. The Wagner experience with frontal assaults over the past months, resulting in tens of thousands of casualties, largely proves this to be true.

It is extremely unlikely that Russia’s regular military can tolerate such extreme loss rates. This makes the prospect of Russia simply bashing through to the borders of Donetsk and Luhansk over the coming weeks extremely irrational.

Now, this doesn’t mean that Russia won’t do it - in some situations it has happily thrown whole units of airborne or marine troops to their swift demise. But assuming they will, given that the loss ratio against Ukraine is unlikely to be favorable, is incredibly dangerous.

Frankly, Russia would be better off trying to reach Kyiv again, especially when the new long-range rocket system the US is sending comes online, extending Ukraine’s ability to target Russian supply dumps in occupied territory. And virtually all of Soviet military history, which Gerasimov is reputed to be a big fan of, implies that successful Russian operations are usually the result of a big Russian force appearing where it wasn’t expected to be, then launching a massive attack.

If Russia does indeed have such a force preparing for a strike, it is more likely to be dispersed and hidden in the Russian-Ukraine border areas that have been under martial law for months now. Not only are these be more difficult for NATO assets to surveil, but Ukraine’s promise not to use US weapons to strike Russian territory means it will have a relative safe haven for logistics and repair troops.

Other clues likely include:

The recent deployment of sabotage teams by Russia in the Sumy region

A steady intensification of cross-border shelling observed between Kharkiv and Chernihiv over the past few weeks

Reduction in artillery bombardments in other areas, possibly to hoard supplies

Visible movement of a newly-trained division from Belarus to Russia opposite occupied Luhansk

Putin’s new demand the military address the sporadic shelling of the Belgorod region, mostly coming from Kharkiv district

Relative lack of tanks on other sectors of the front, though Russia’s factories have produced at least a couple hundred since the war began and refurbed many times that

Fairly limited action by Russian aviation, which at some point will have to make a push to control the skies over the front line, if nowhere else, but likely has needed to train up pilots

The end of joint drills with Belarus, freeing up additional resources for use in Ukraine

Shift in the frequency of strikes on Ukrainian infrastructure, including renewed use of Iskander ballistic and Kinzhal hypersonic weapons

In addition, the recent reshuffle at the command level and restoration of Gerasimov to a leading role implies he was busy organizing personnel and training ahead of a new offensive, which he will now oversee. Here again capacity to expand the front is being built up, implying a new offensive in the near future.

So where will it be? Most likely, wherever Russia believes a new assault will stand the greatest chance of cutting Ukrainian forces fighting in Donbas off from the rest of the country.

To defeat all of the 200,000+ active soldiers Ukraine has in the fight right now, Russia needs far more than the 300,000 it says it has mobilized or even the 500,000 reports indicate it might actually have. Just sending wave after wave through Donbas will not only waste resources, it will also make Russia look incredibly weak and might not work. A big enough force has to be concentrated somewhere to have the kind of numbers advantage needed to move the front lines.

In addition, Russia also now claims territory across the Dnipro river in Kherson province as sovereign lands. It is unlikely that Putin will back down on this claim now, but crossing the Dnipro will likely be beyond Russian capabilities for years at this point.

This makes it likely that Russia will need to secure a bigger prize if it hopes to force Ukraine to make concessions in any future negotiations. Scattered reports that Russian military leaders have been discussing the seizure of Kharkiv could be a bluff, but track very well with my suspicion that they intend to take the straightest road from Russian territory to the strategic river crossings at Dnipro.

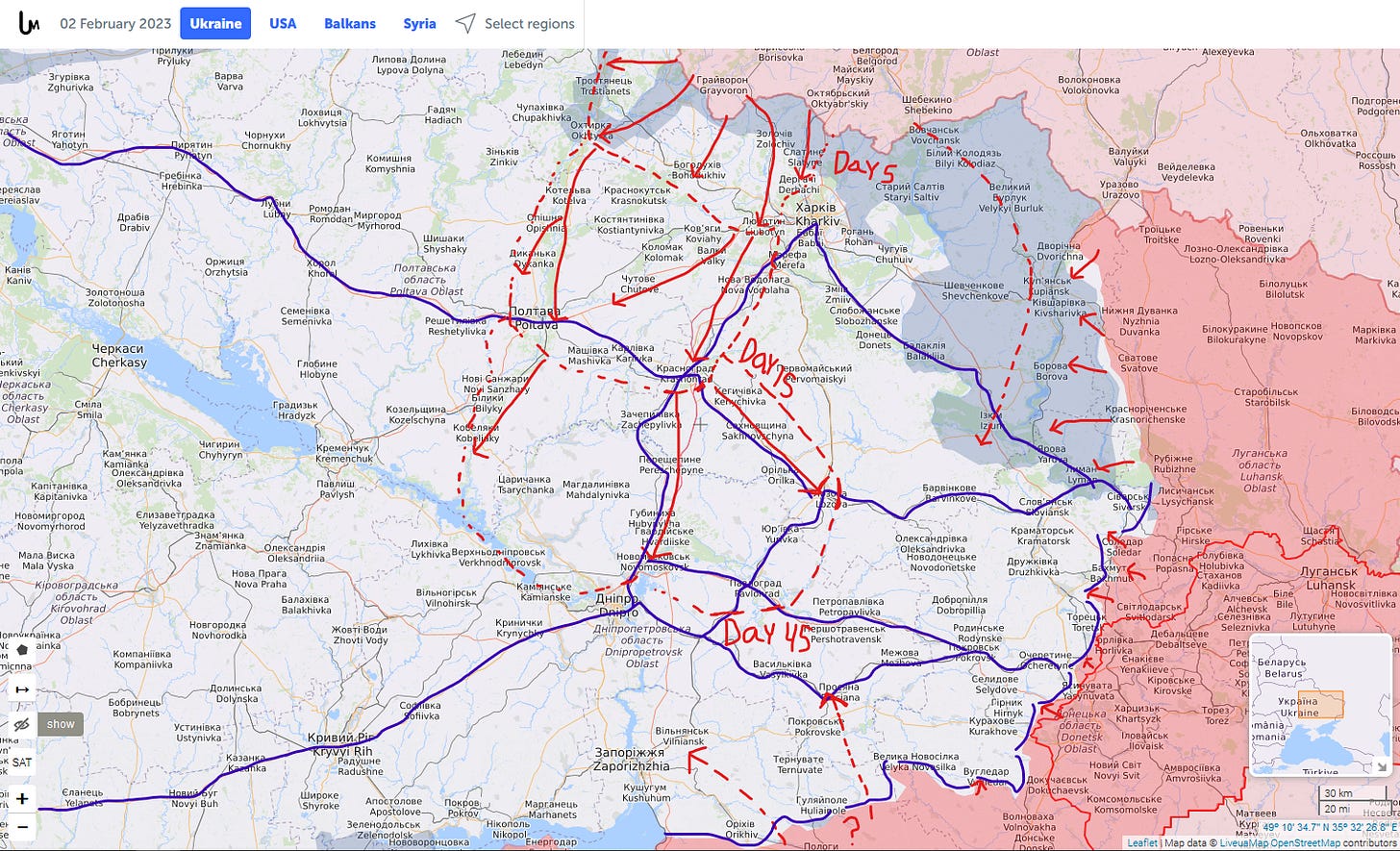

Here’s a rough map of eastern Ukraine to illustrate the threat:

If successful, an operation like this would be a devastating blow to Ukraine’s military, and put the also-claimed city of Zaporizhzhia at risk too. I suspect Ukraine would survive and probably reverse Russia’s gains during the summer, but might well not have enough combat power to push to the Azov Sea as it hopes to this summer.

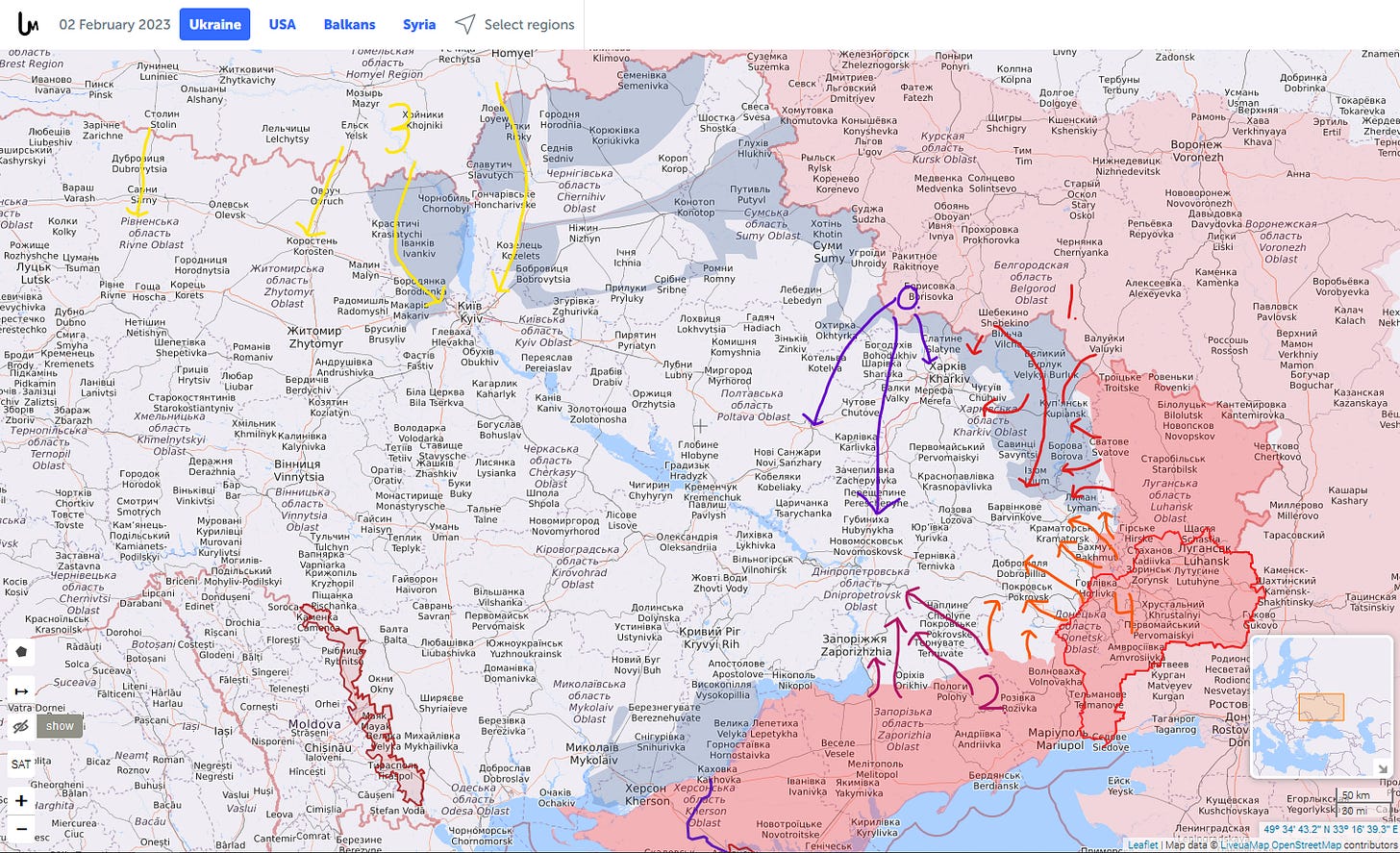

Ukraine’s end game looks something like this: its forces reach the Azov coast between Melitopol and Mariupol, then strike the Kerch Strait bridge to isolate Crimea. Small landings begin and the peninsula’s military bases are struck by drones and missiles. Putin is forced to make a nuclear demonstration, which results in such severe global backlash his regime falls to a military coup. The new regime is forced to accept a withdrawal to pre-2014 borders, reparations, and a war crimes tribunal in exchange for progressive normalization with the rest of the world.

Russia’s end game is surrounding the biggest chunk of Ukraine’s military presently deployed and holding Kharkiv, Dnipro, and Zaporizhzhia hostage until Zelensky negotiates. If he doesn’t, Russia can proceed to lop off other bits of Ukraine east of the Dnipro, eventually moving on Kyiv. And from there, who knows? He might even decide the war with NATO has to end in his lifetime.

For both sides, the conflict is now existential, and so it can only escalate from here barring Putin’s early demise.

Still, the odds that a blogger using open source information independently worked out Russia’s plans are low. So in addition to my own theory, I’ll conclude this with an outline of some other likely avenues the coming Russian offensive might take.

Retaking Izium

Here Russia tries to put its original plan for breaking through in the north of Donbas into action, hitting the Ukrainian lines where it did last year and driving south across the Siverski Donets while the grind past Bakhmut continues. A weakness of this approach is that Russia would be fighting over ground it had once held and ostensibly heavily mined. Another is that Ukraine appears ready for this.Southern Strategy

In this one, Russia manages to mass enough forces along the Azov coast to go on the offensive in Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk, with the recent attacks on Vuhledar a harbinger of what is to come. Problem here for Russia is logistics, as the main bases are all fairly exposed to Ukrainian rocket fire, plus the fact that Ukraine can quickly reinforce this region and probably will when it is ready to go on the attack.2022 Redux

Russia might also use its buildup of personnel and close ties to Belarus to hit Ukraine at all points of the compass. Any success could be reinforced with reserves, straining Ukraine as it tries to counter attacks everywhere. This option shares the same weaknesses as the first go round: Ukraine is better at decentralized fighting.Donbas Grind

Finally, Russia could cast all military sense aside and just keep pushing against Ukraine’s best troops until someone bleeds out. Leaders have done dumber things before, and the tendency once in a situation is often to double down on what got them there in the first place.

A quick and dirty map to illustrate the challenge Ukraine still faces - which is why it needs way more tanks than it is getting, and modern jets too:

In conclusion, a new and perhaps even more terrible phase of the war in Ukraine is about to begin. Two military systems are locked in mortal combat, each with its own advantages and weaknesses.

Which one wins will come down to the same thing wars always do: the tenacity, creativity, and bravery of the soldiers forced to wage them. Provided, of course, they are kept in supply.