Russia's 2023 Winter Offensive: Week 4

Bakhmut still holds, while Russia's new assault doctrine reveals how little it cares for its own soldiers.

A full month of tough winter fighting has left Russia with precious little to show for it. Only in the Bakhmut sector have Russian forces made consistent progress, and only at extreme cost.

The fog of war is thick in Ukraine right now, yet it appears probable that Russia has still not committed the bulk of the combat power it began building up last September.

The weather in Ukraine has now reached that critical turning point between winter and spring where a sudden lasting thaw could bring the bezdorizhzhia, the muddy season.

Southeastern Ukraine is one of the world’s breadbaskets for a reason: the soil is ancient, rich, and runs deep.

There is actually a case to be made that Russia’s war on Ukraine is the biggest climate war yet seen. While I don’t agree with the recent tendency to try to connect each and every weird weather event to climate change, the fact of the matter is that future climate uncertainty coupled to rising global populations can and will make arable land a vital geostrategic resource in the coming decades.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, global agricultural systems produce enough raw calories to feed up to twelve billion people given current technology. Even if that capacity is reduced by 20% at some point in the future because of climate shifts, the world’s population will top out at around 9 billion in 30-40 years.

The real reason for famine in the modern world is not lack of capacity - it’s politics. Distribution systems don’t work right because of governance issues like corruption.

Russia’s leaders have clearly decided on becoming a gigantic version of North Korea in the short run, and over time to unite all countries hostile to the Anglosphere and Europe in a bloc of resource-rich countries. Oil, natural gas, rare earths, food, and water are still the vital materials that underpin the global economy, and those with guaranteed access to quality sources will experience fewer price swings and less social volatility in the long run.

Putin’s regime has absolutely committed itself to Russian imperialism and stamping out any rivals to rule from Moscow, hence the genocidal, culture-annihilating character of the assault on Ukraine. But totalitarian regimes always operate with one eye on the future, doing things that seem crazy in the short run in order to gain a long-term advantage.

This doesn’t mean they’re actually any good at it - in fact, captured training documents covering assault operations at the tactical level imply that Russian military science is around 80% clever, 20% addicted to a kind of intellectual methamphetamine that utterly crushes the potential of the rest.

A tendency reminiscent of too much American strategic thinking, to be honest. Fortunately, Russia has a concrete and plausible strategy but lacks the means and skill to put into effect, while American leaders’ chronic ineptitude is generally offset by the professionalism of the people who work for them.

In any case, back to the soil: It is a mistake to think of the transition from winter to spring in this part of the world as being instant. While March is considered to be the start of spring, soil thaws in stages, getting progressively more difficult to work with as average temperatures increase.

This means there is no calendar cutoff point where it will be clear that major Russian offensive operations cannot begin. Truth be told, Russia’s reliance on road and rail networks might mean that seasons won’t matter as much as some other hidden factor, and the ongoing Winter Offensive will blend seamlessly into Spring, escalating steadily.

But generally speaking, trying to stick to roads in a fight like this is a surefire way to get people blown up by artillery. Mud is best seen as a constant drain on combat power and efficiency, accelerating the inevitable deterioration of organization and effectiveness that comes with moving large numbers of people and their gear across a battlefield.

If Russia is planning a major push on a new front, it might be hoping to take advantage of the predictable worsening of the mud through March. While I expected Putin’s generals would want to leave themselves plenty of time to advance before the mud gets bad, they might in fact be hoping to use it as a shield.

Russia might, aware of the danger of its forces running out of steam and getting hit by a massive Ukrainian counterattack, be aiming to revive the old Seven Days To The River Rhine concept from the Cold War. This would take the form of a lightning-fast dash to the Dnipro in 1-2 weeks with an elite armored force backed by concentrated air power taking advantage of Ukraine’s focus on the Donbas front.

My standing evaluation remains that if Russia cannot cut off the flow of supplies coming across the Dnipro river, its army will bleed out in Donbas by the middle of 2023.

Though spring has technically begun in Ukraine, the mud might well not get bad enough before April to hinder the cross-country pushes between major highways and rail lines that Russia would have to make to advance west of Kharkiv. The steadily worsening mud was likely part of the reason Russia was forced to withdraw from the northern part of Ukraine in the first week of April last year, as its logistic lines would have become even more difficult to secure once available road space had dwindled.

Frankly, the bigger impediments to a major Russian assault in spring will be the increasing water levels and blooming foliage. Crossing water lines is always difficult because of the limits they place on armored vehicle movements, but when snow melts the challenges are magnified.

Ukraine will also run into troubles crossing water bodies with armor, especially as Leopards and Challengers reach the front, as they can’t cross most bridges in the region. This fact limits the scope of Ukraine’s anticipated counteroffensives this year, likely forcing Kyiv to wait on its biggest strikes until July and focus on only a few routes to the Sea of Azov.

Vegetation growth poses another problem for an army on the attack: it makes surveillance even harder if the enemy can hide in grassy fields or under leaves. Bare trees do offer cover, but leafy ones are even better at producing naturally camouflaged spaces. Yes, cover does make advancing without being seen easier, but in dense conditions defenders tend to have extreme advantages because they typically get the first shot in.

So if Russia’s commanders recognize that they have to open a new front to win this war, as I theorize, but are wisely concerned about the danger of Ukrainian counterattacks, they might time the attack so that Russian forces would reach the Dnipro, covering a distance of around two hundred kilometers, at the moment it became easier to defend the territory they had seized.

This would force all of Ukraine’s logistics going east to run across a half dozen or so bridges between Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia. And even Russia’s air force can probably damage them beyond repair if it is willing to endure the casualties and depletion of precision weapons. If that works, Ukraine will be in serious trouble.

However, I could be - and hope I am - completely wrong. If the captured manual I’ll discuss below is any indication, all Russia has left is a long bitter grind in Donbas until its army finally collapses on the outskirts of Sloviansk.

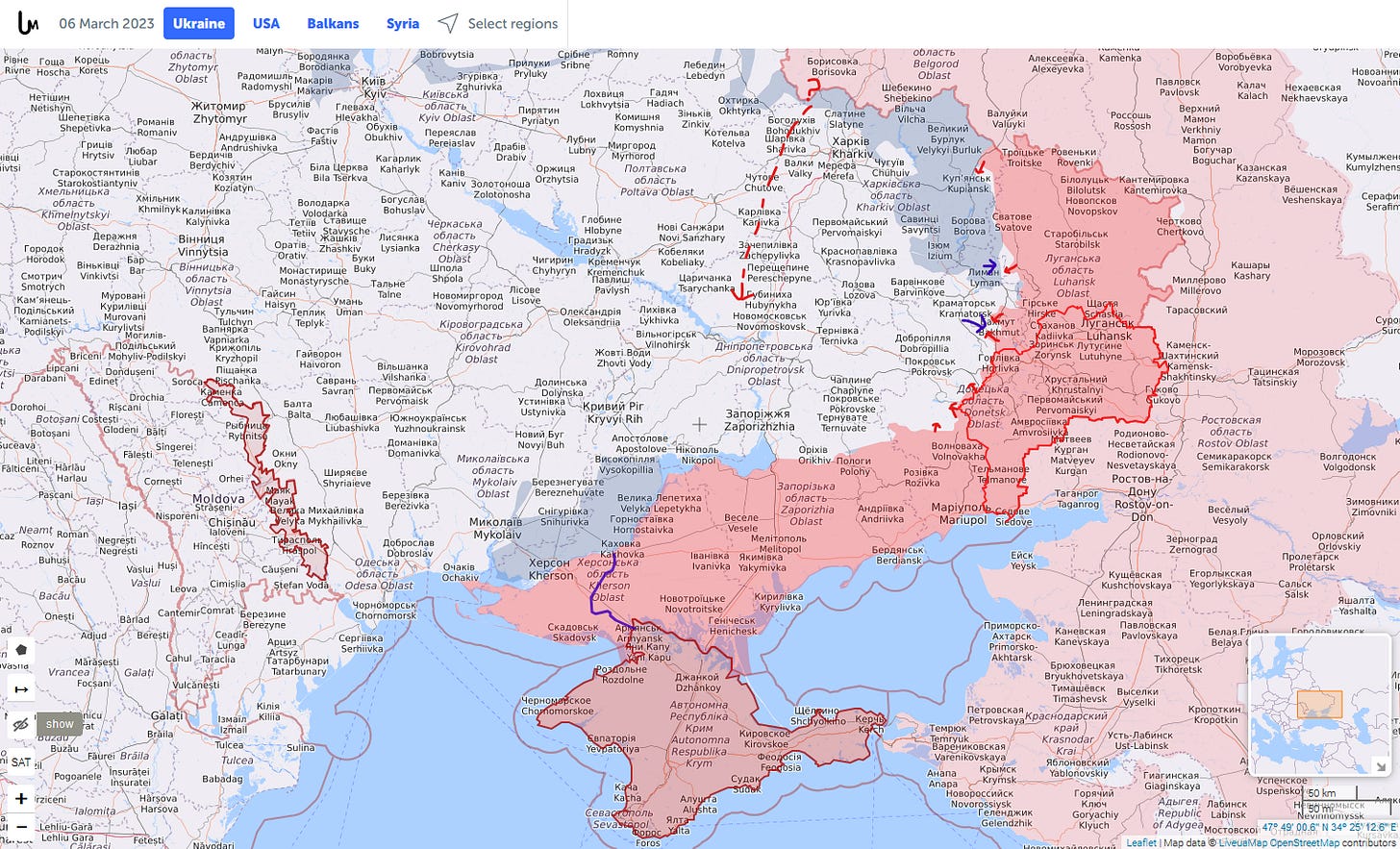

As to the situation along the front, only in Bakhmut has anything significantly changed.

Aside from scattered raids like that odd incident near Bryansk, constant shelling plus a few drone strikes, and the ongoing construction of defenses, Russia continues to do very little between the mouth of the Dnipro west of Kherson all the way through Zaporizhzhia to the edge of Donbas. There, at Vuhledar, Russia is apparently massing a large force but dealing with an effective mutiny by soldiers there who are being told to assault Ukrainian forces with inadequate preparation or support.

In this area Russia appears to be trying to push back a couple Ukrainian brigades by striking at Vuhledar and Marinka, further north. Aside from drawing Ukraine’s attention and maybe a few reserves, these strikes have accomplished little, and even if they do eventually make progress all this will mean is a little more distance between Ukrainian forces and occupied Mariupol.

Along the old line of contact to the north, Russia keeps applying pressure on the outskirts of Avdiivka, a town that is essentially another Ukrainian fortress blocking Russia from advancing down the main highway in southern Donetsk, the M-04 leading to Pokrovsk. They’ve been at this for months, only at a lower intensity than what the world is seeing in Bakhmut, Verdun reborn in truth, and have only managed to secure a couple villages, Piske and Optyne, on the edge of the ruined Donetsk International Airport that was the site of heavy fighting back in 2015.

Jumping past the embattled Bakhmut sector to the north, Russia has maintained a fairly high tempo of operations, as professional staff officers like to call it, at various points along a hundred kilometer arc going from Kupiansk in the north to Zarichne in the south. The other day Ukraine ordered residents of the former, liberated last September, to evacuate, which likely indicated an imminent Russian push here.

On the southern end of this sector the last bit of Luhansk still free, Russian forces continue to attack west from Kreminna, which just a couple months ago was under threat by Ukrainian brigades pushing into Chervonopopivka and a major forest preserve close to the Siverski Donets river. Not much news is coming from this fight, but it appears to involve some of Russia’s elite units, given the appearances (and destruction) of T-90 tanks and the new BMP Terminator tank support vehicle.

Ukraine also apparently moved a brigade that had been resting in Kramatorsk, likely the 24th Mechanized, to Zarichne. Whether as reinforcements or to rotate out a brigade that has been depleted I can’t say, but regardless, Ukraine’s progress towards Sievierodonetsk has been halted.

Only in Bakhmut has Russian progress been notable, but coming at severe cost: media reports suggest Russia is on the losing side of a 7:1 casualty ratio, which not even Moscow can sustain forever.

Ukraine’s population is about a third of Russia’s. Unlike Russia, it allows women to fight on the front lines, and is augmented by foreign volunteers. Even in the crudest, grossest terms, Russia simply cannot sustain this loss ratio forever. At some point, even Putin’s allies will have to question the sanity of sacrificing hundreds of thousands of productive citizens to seize 20-25% of Ukraine, even if it is rich farmland with substantial heavy industry.

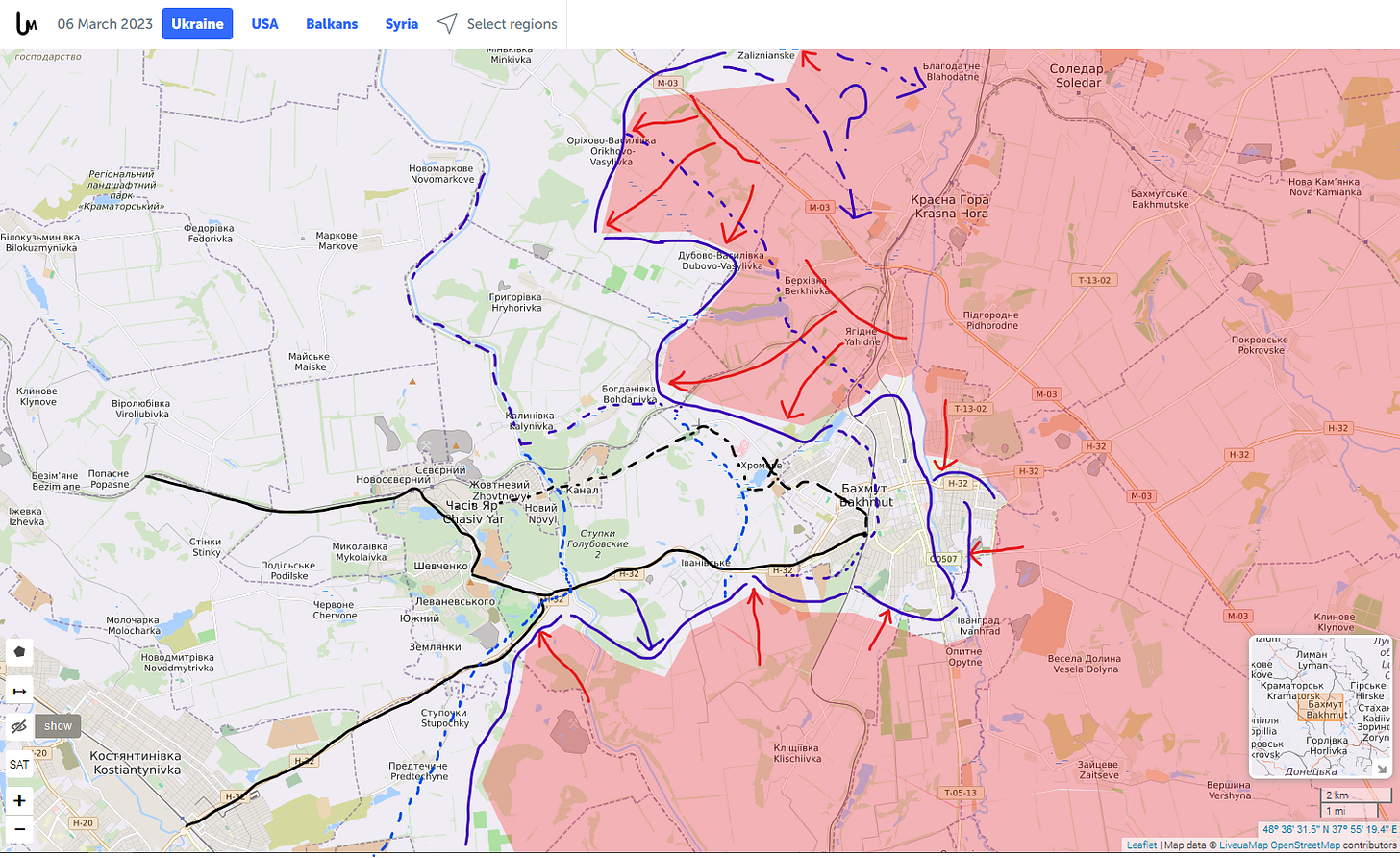

Russia’s progress in Bakhmut over the past week has led many analysts to assume the city is lost. And indeed, the maps of the area look very bad, Ukraine’s defenders in a textbook example of a pocket, in military jargon, a salient some ten kilometers long and five wide.

Instead of trying to punch through the city itself block by block, Russia clearly hopes that by threatening to cut off the defenders’ final avenue of retreat back west that Ukraine will be forced to pull out. This would in fact be a very sensible approach for Kyiv, because Bakhmut has more than done its job of forcing Russia to exhaust combat power at apparently reasonable (if heavy and tragic) cost to Ukraine.

However, there are some early indications that Ukraine might instead press a limited counterattack. I have been a bit surprised at how far the Wagner-led attacks have pushed back the northern edge of the Bakhmut defense zone - penetrations five kilometers deep on two separate axis, one approaching Khromove and apparently destroying a bridge that was formerly one of the last routes into town.

Initial reports last week of a Ukrainian counterattack down the M-03 highway into the rear of the Wagner advance turned out to be either exaggerated or false. However, Ukraine has definitely deployed more forces to Bakhmut in recent days than seem needed to cover a withdrawal, and the first Leopard 2A4 tanks from Poland appear to have joined a tank brigade defending the highway leading to Sloviansk.

Ukraine has already reportedly mounted local counterattacks on the southern end of the line to keep the H-32 highway leading back to Chasiv Yar free. But if these were joined by a 3-4 brigade push down the M-04, that might catch Wagner forces when they are strung out and weakened. A combat test of the Leopards would also give Ukraine valuable information about the challenges it will face keeping modern armored vehicles in the fight and playing to their strengths: long-range sniping of valuable targets like tanks on the defense, the same with a strong chance of surviving when moving forward.

It is also entirely possible to withdraw some forces from Bakhmut while attacking with others. The advantage of holding a fortress is that it gives the defender options, provided they don’t get too attached to winning at any cost.

That is precisely what Russia wants, and what it is apparently training thousands of conscripts to deal with.

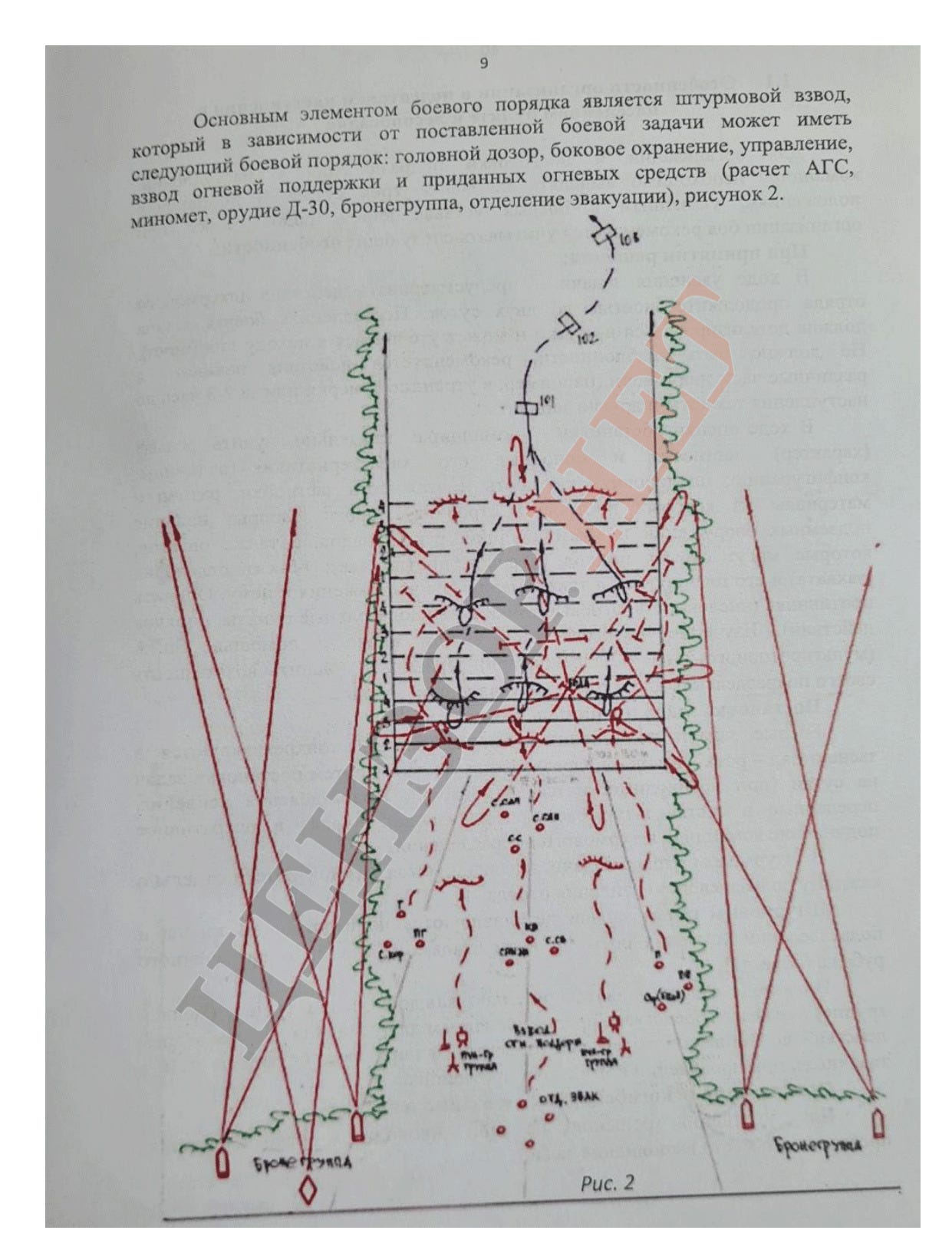

Over the past week, a fascinating captured document and some insightful analysis about it - along with the usual self-protecting nonsense from too many Western sources - have begun making the rounds online. It details, from a junior level officer’s perspective, how assault operations against entrenched Ukrainian units in forests or urban areas are supposed to go.

These kinds of documents reveal a tremendous amount about a military system if you know what to look for.

To keep all its moving pieces organized, every military has to develop a training curriculum that teaches members to behave a particular way. There is no right or wrong way to to this - it is a form of basic applied science, though one scorned by most people with PhDs. What works rules the day in this world, because the lives of a lot of people are on the line.

An organismic, ecological view of military affairs rooted in systems theory is absolutely vital to understanding war and warfare - and humanity, too. War is the ultimate laboratory for studying human behavior because it creates a natural experiment that tests all assumptions under the most horrific of conditions, revealing the underlying structure of the world as it actually exists, not as ideologues want it to.

What is fascinating about this Russian training manual from a systems perspective is what it reveals about the broader Russian way of war. Sadly, it confirms that the inner workings of the Russian military system are so rotten that sending men to their deaths is now an end in and of itself for senior Russian officers.

Ostensibly, this manual teaches junior officers how to use the array of tools in their arsenal to punch through Ukrainian lines. I’m pleased to see that I’m not the only person who sees value in showing scribbled-on maps as a communication tool, but better yet is seeing confirmation of one of my theories about the future of warfare: Russia is clearly attempting to create self-contained combat cells capable of independently taking and holding vital ground.

Because of the spread of cheap remote sensors and the accuracy of satellite-guided artillery, in modern warfare the number one rule is now this: once seen, soon killed.

Survival - a prerequisite to accomplishing any mission - is dictated by avoiding being seen for as long as possible, then responding with superior firepower and speed to eliminate threats before moving back under cover as quickly as possible, This is true whether you are attacking or defending - in truth, these concepts are almost useless nowadays given that everyone has to be ready to do both at any time.

Every cell, or team, if you prefer, also has to be able to defend itself against any threat it can’t run from. Crippling attacks can come from the ground, air, water, or electromagnetic spectrum, so every ground unit that wants to be able to fight on its own for any period of time needs to have anti-aircraft, electronic warfare, and anti-tank weapons, even if they have only short range.

They then need to be partnered with more specialized units operating a ways behind the lines that offer what you might say are on-call services, like heavy artillery, mine clearing, and deep recon as well as long-range air defense, logistics, repair, and other functions. Communications are essential, obviously, to keeping everyone in touch and organized.

This cellular structure allows each group to disperse and hide scattered across the landscape, entering the fight when and where they are needed. Combat-focused groups naturally have to cover the front to create a relatively safe space for specialists to move around without having to worry about being directly shot at, while a command group works to keep everything coordinated.

Russia has been trying to kludge together an incomplete, forced version of this concept for years now. The battalion tactical groups used at the start of the invasion were supposed to be full-spectrum teams capable of fighting on their own, but they wound up being too big and armor-heavy to operate without adequate protection for their supply lines. They were never able to hide their location, got picked apart by artillery whenever they massed to try and do anything, and had huge logistical tails.

At the tactical level, BTGs never figured out how to have a few tanks and infantry teams work together to take and hold space, backed up by artillery and air power. A big part of the reason why is that to pull off any decentralized system an extreme tolerance of subordinates doing their own thing is an absolute must.

People on the ground always have a better sense of what is happening to them than anyone else. Leaders in a distant command center may have a better view of the totality of the situation, but too often forget that this emerges from all the actions and interactions of humans actually going about the work of making war happen.

The quality of information decays with time and distance, and having to wait for orders means surrendering opportunities to take actions when they could have the most impact. However, allowing local-level personnel to make vital decisions requires a kind of discipline and self-awareness too many professional officers lack.

Their promotion usually depends on staying in good graces with their fellow officers, always respecting the traditions of their particular institution. Over time, however, groupthink will always grip any cloistered institution unless major events force a reboot of stale ideas. Unorthodox or experimental approaches are squashed for fear of upsetting the existing order, and when war comes senior officers are often totally unprepared.

Then, when they try to change their approach on the fly, too many wind up latching onto successes early in the conflict that took place under conditions that will never be replicated again because both sides are constantly learning and evolving. The new Russian approach is apparently derived from Wagner’s experiences, and reflects the same callous approach to personnel that has led to extreme casualties.

While Putin might think it cost-effective to send prisoners to their deaths in mass waves, the hidden costs of this approach start to become visible when the wrong lessons are learned and spread across the broader fighting force.

Russia’s assault doctrine basically relies on wave after wave of 15-man assault platoons working in 3-man teams, each with their own special role, pushing straight into Ukrainian trench lines with a few tanks and infantry fighting vehicles covering their flanks. Within a minute of the conclusion of a massive bombardment with grenade launchers used as small-scale mortars plus fire support from a single artillery piece or heavy mortar, the assault teams go in with cover from everyone else and some shock troops with thermobaric grenade launchers.

It is hard to imagine what facing this assault on the ground is like - even watching combat videos only tells part of the story. I do not mean to make light of what Ukrainian troops are dealing with.

However, it is clear from this manual that a large segment of Russia’s infantry are basically being sent to slaughter in hopes of pushing Ukrainian forces back a few hundred meters. Artillery will rip attacks like this right up, and modern armored vehicles will play a vital role too.

One of the key details to note is that assault teams are forbidden from stopping to assist their own wounded or taking shelter in Ukrainian trenches because these might have booby traps.

True that, but the conditions in each trench will be so different no matter the threat from incoming fire that making this a standing policy implies something wicked: Russia wants assault teams moving forwards at all costs. Russian officers are deliberately sending men to their deaths to slowly drain Ukrainian forces of ammunition, trying to apply constant pressure to make them retreat when they run out of bullets.

Ordering soldiers to ignore their wounded comrades, leaving them to be helped by dedicated evacuation teams, is likewise nothing more than deliberate cruelty in transformed into policy. Evidence from every recent war has shown that the minutes after a soldier suffers an injury generally determine whether they live or die - and living soldiers can teach new recruits what mistakes to avoid even if they personally can’t return to the fight.

There is a good reason US troops are given intensive training in basic medical care and will absolutely turn away from combat to treat an injured comrade. They operate in three or four closely-linked fire teams with four soldiers each to make sure that if someone in a fire team goes down the squad can defend the evacuation effort conducted by their three comrades, which begins immediately.

Medics are supposed to be embedded into platoon-level formations, with at least basic facilities for treating the wounded located at the nearest battalion-level headquarters. Soldiers are an investment, and what’s more, they respond to the way they see other personnel being treated.

American soldiers can nearly always fight confident that if they take a hit they will have reasonable survival odds. This makes them more willing to take appropriate risks and even rise to take command of their unit if a leader is lost.

Russian soldiers, by contrast, can’t help but quickly learn that they’re just meat to their officers under a system like this. Apparently, The 9th Company wasn’t kidding about what Russian military life is like. Relying on separate evacuation teams to handle the wounded is basically admitting that no one may come, because the officer coordinating everything will always have other concerns - or got taken out by Ukrainian artillery after the HQ location is triangulated based on radio transmissions.

Broadcasting, by the way, is yet another way to be seen in modern warfare. That’s why combined arms teams meant for combat have to be able to engage any category of target they are likely to encounter that they can’t run from, but also need to have a limited range weapons and tasks to perform so units remain flexible.

In a post originally on Medium but available in my Substack archive, I lay out a rough vision of what this looks like. I’ll probably update it in the near future given ongoing lessons, but in short, I am certain Ukraine can take out these Russian assault teams with relative ease once they have more modern equipment.

From top to bottom, Russia’s new Wagner-inspired tactics are a recipe for continuing to lose a lot of people. It’s like transporting the tactics of 1945 to today and expecting to win.

The open question is this: are all Russian troops being trained to this standard? Or is this the training being given to the poor orcs forced to grind it out in Donbas, where after Bakhmut Russia will have to look to the even larger and better-defended targets of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk?

If Putin believes Ukraine will run out of ammunition before he does, maybe. But Soviet practice was to have its divisions categorized according to their capabilities and training. The USSR had some units with obsolete gear and little training ready to mobilize for less intense sectors alongside a large number with middling equipment - and a few elites with the top of the line stuff.

The captured documents indicate that Russia’s assault units are being filled with gear from the second category, the tanks all being T-72s and infantry fighting vehicles mostly early model BMPs. And In proportional terms, Russia has lost more of this level of equipment than it has the newer T-90 or even T-80 tanks tanks. The old T-62s being pulled out of storage appear to be showing up in defensive positions in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, not placed at the disposal of assault teams fighting to take Bakhmut.

So two vital questions remain: Does Russia have an elite guard dispersed in Belgorod and Kursk preparing to open a new front in a short, sharp, Soviet style bulldozer campaign? If so, where will it strike?

My bet is still on Kharkiv, with the point of the spear lunging towards Dnipro.

But if the new front is not opened before early April, I suspect it never will be at all. And that may mean Putin is down to his last throw: the nuclear option.

At least, one way or another, there is a decent chance this war will end in 2023. Here’s hoping Russia’s military understands where this is all heading and moves against Putin soon.

But the coming month still looks very tough for Ukraine. And as I edit this, air raid alarms have gone off throughout the country again. The next week could be decisive.