The Failure Of Russia's 2023 Winter Offensive

As spring reaches Ukraine, the war is set to enter another new phase

All in all, it seems safe to say that Russia’s major winter offensive has failed, and ongoing operations along the front line are mostly an attempt to drain Ukrainian resources as much as possible ahead of its summer offensives.

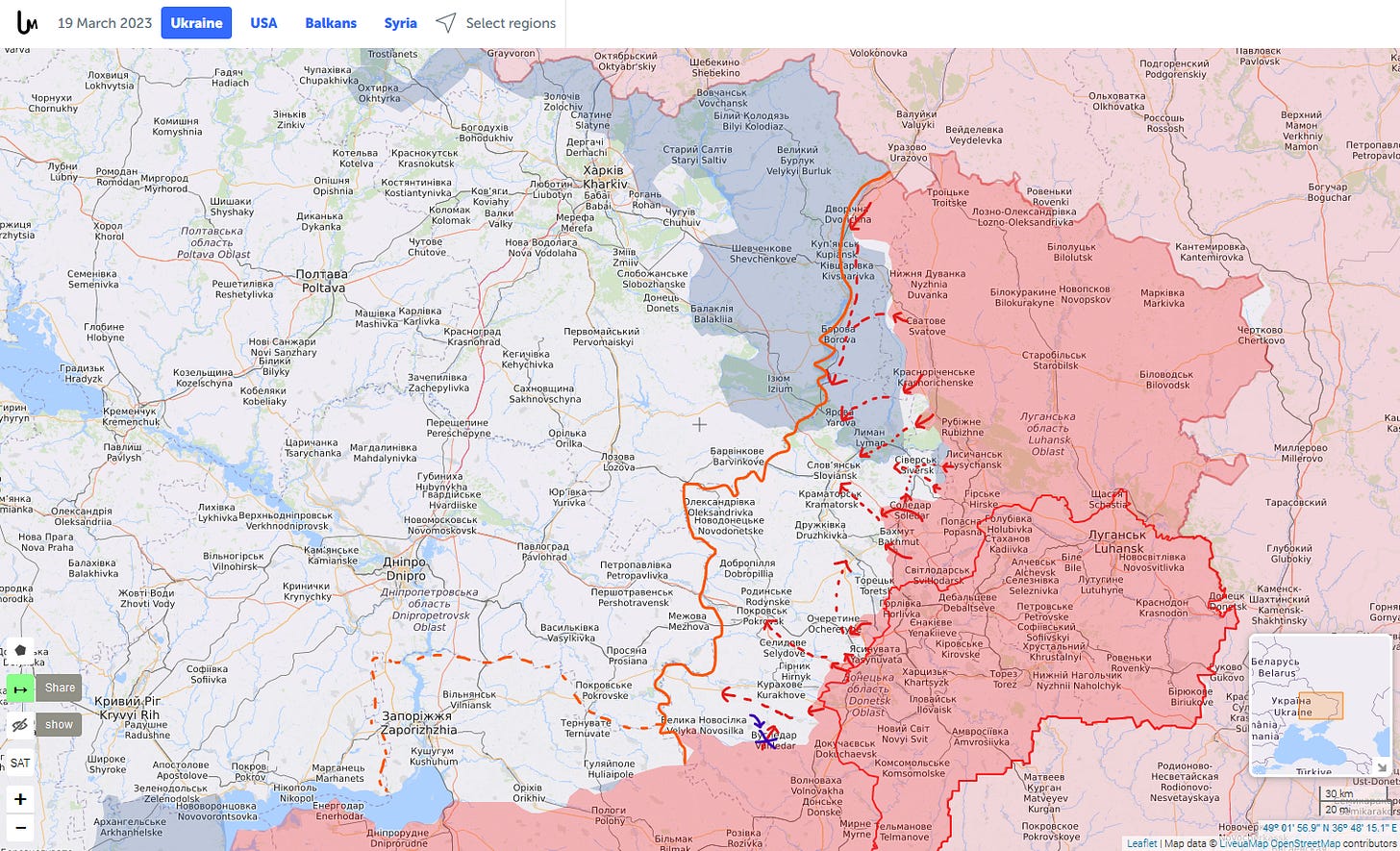

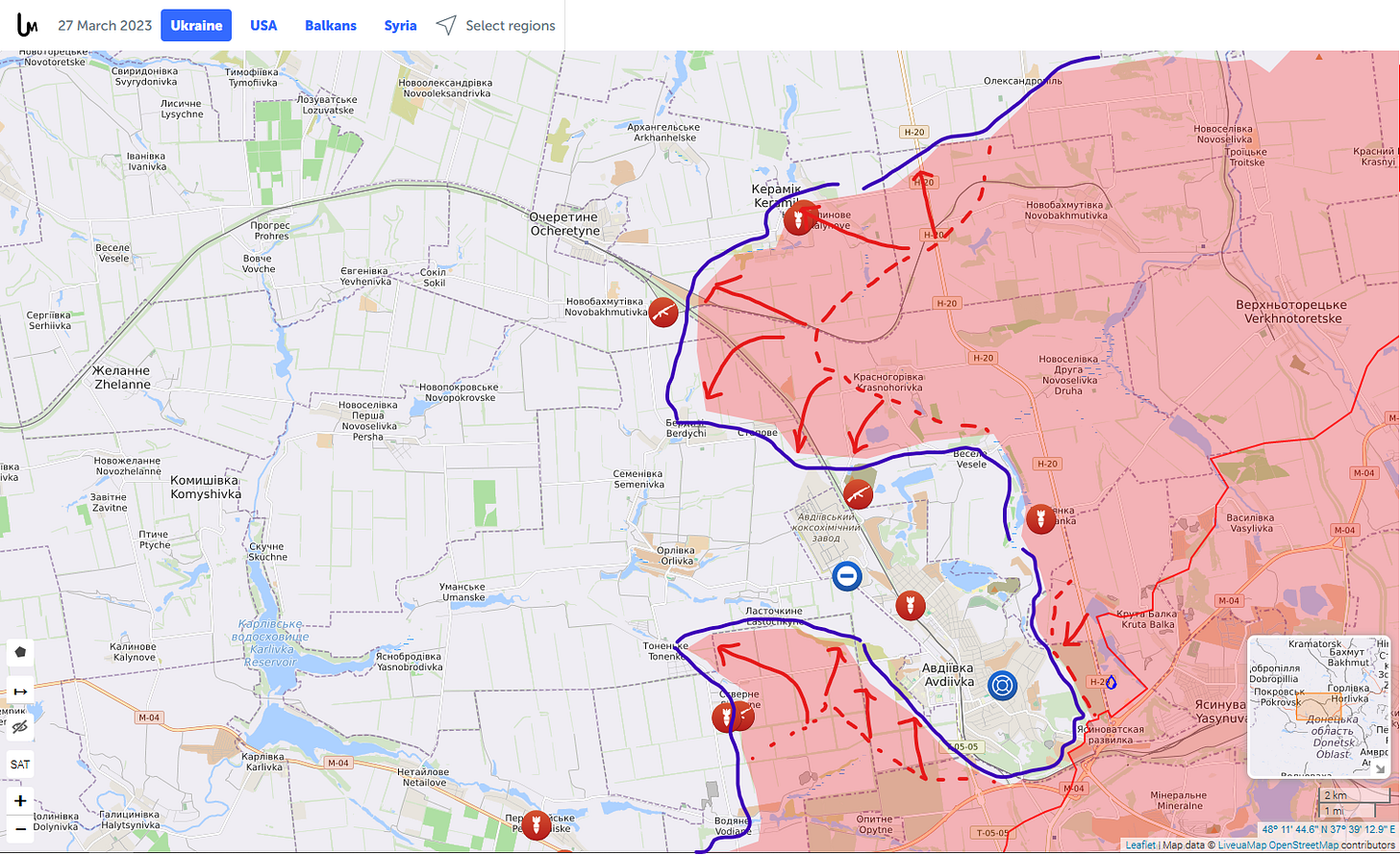

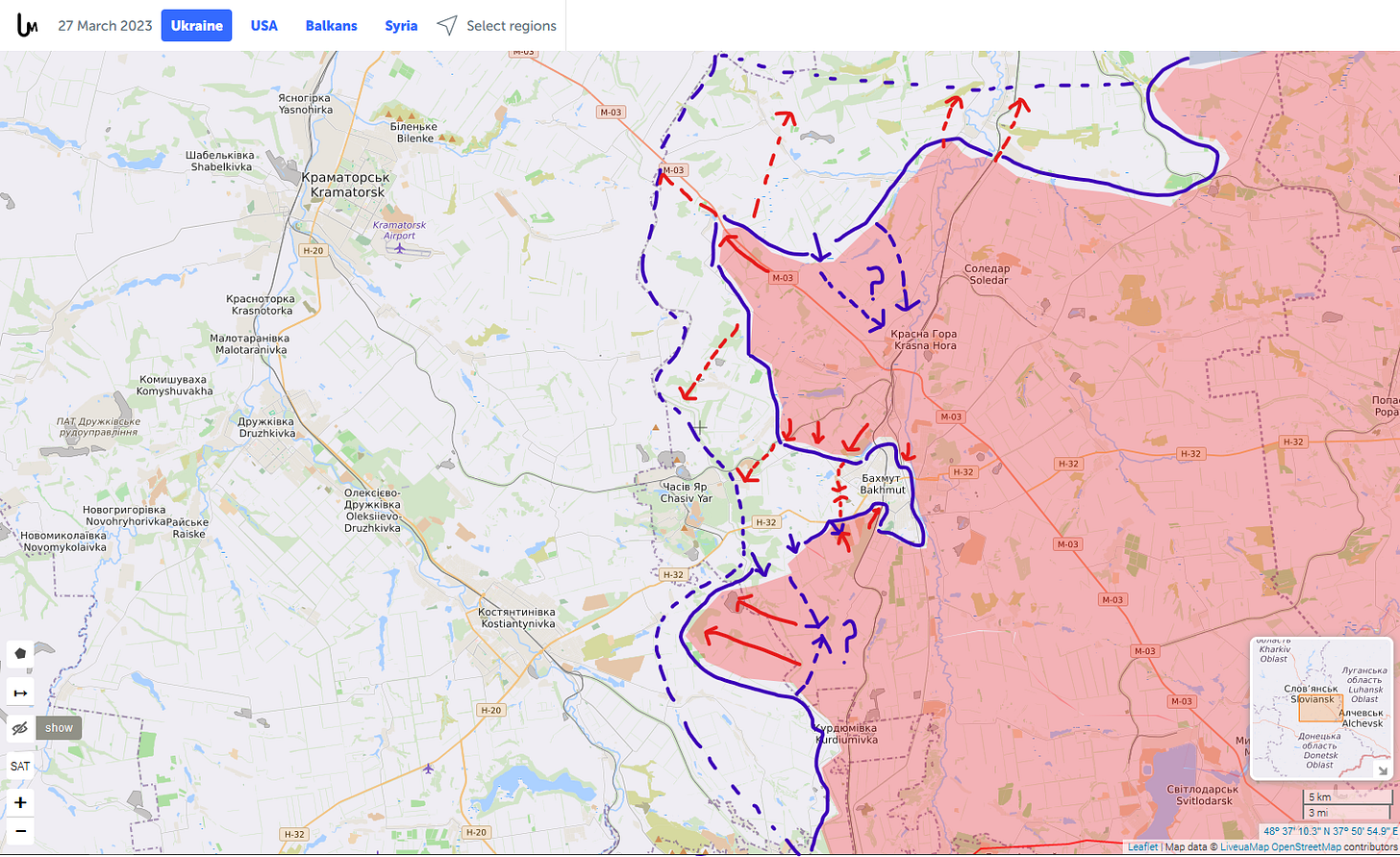

Over the past week Russia’s offensive has continued grinding forward in Bakhmut and Avdiivka, threatening to turn the latter into a smaller repeat of the former.

To offer an example of the wildly different scale levels of the fighting in Ukraine, the above image shows the entire Donbas front while the below zooms in on that little set of arrows just north of the ones showing the failed attack on Vuhledar-Marinka, at the southern edge of Donbas.

Doesn’t look like much zoomed out, but if you’re sitting in the town of Avdiivka with Russians expanding their control of territory along either side, all you really care about is how soon reinforcements will come.

Elsewhere attacks towards Kupiansk and Lyman have failed, though not as badly as the ones at Vuhledar. Other than that the war has seen little change this past week. Russia attacked with a few more Iranian drones and made some more nuclear noise, announcing that it would station tactical nukes in Belarus, but this appears to be just some more saber-rattling intended to discourage anyone from sending Ukraine fighter jets.

Some minor encouraging news has emerged on that front, with Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Norway announcing an effort to coordinate a joint air force that could pave the way for some modern jets to head Kyiv’s way. The major argument made against giving Ukraine more and better gear has always been the impact on donor country defenses, so putting four reasonably effective air forces together should create a pool of spare aircraft Ukraine could inherit, whether F-16s from Denmark or Norway, F-18s from Finland, or Swedish Gripens.

In the meantime Slovakia is flying a squadron’s worth of MiG-29 fighters to Ukraine in small groups, which is interesting as another argument NATO countries have been using over the past year to insist they can’t give fighter jets is that the transfer itself could give Russia an excuse to attack the donor country. Apparently, someone in NATO finally looked at a map and realized that the furthest western reaches of Ukraine adjacent to Slovakia are well beyond areas Russia can hope to reach unless it wants to sacrifice more fighters in the process than it could possibly shoot down.

In any case, Poland has been disassembling its old MiG fighters for use as spare parts for a year and is likely to send whole aircraft soon, which will help keep Ukraine afloat for a while. Now that HARM anti-radiation missiles have been adapted to MiG-29s, if the new GPS-guidance kits Ukraine is being sent are also compatible that will give it at least some ability to offer fire support to ground forces, sometimes.

That however will remain exceptionally difficult so long as Ukraine lacks any counter to Russian MiG-31 and SU-35 jets equipped with extremely long-range missiles. But they can’t be everywhere, so if and when modern jets reach Ukraine it should be possible to set traps for Russian aircraft even though US-made air-to-air missiles lack the range of the best Russian weapons.

Meanwhile, on the ground the horrible grind continues. Bakhmut remains in serious danger, but Russian attacks have not gained too much ground in the past week. Talk of local counteroffensives is rising, and appears justified, assuming Wagner is truly running low on steam and has left its flanks vulnerable. The situation in Avdiivka may force Ukraine to launch a local counterattack there as well, but no hard news has emerged yet.

The Ukraine War is the first major global conflict to take place in a world where video footage direct from the front lines is available to virtually everyone with an internet connection.

This makes it possible to a degree never heard of in past conflicts for independent analysts to document and study two military systems locked in existential conflict.

In addition, the awful conditions soldiers on both sides are forced to endure are visible to anyone with the will and stomach to see.

I ran across an intense video posted to social media this week shot from a drone providing support to a team of Ukrainian troops defending a tree line somewhere in Donbas.

Fair warning: people die, though the zoom distance is far enough to avoid showing anything too graphic.

Unfortunately, war will never be brought under control unless and until people everywhere develop an inherent allergy to the very idea of letting wars happen. The best and probably only way to instill that loathing of violent conflict is to make people experience it, which is why war veterans tend to be among the most ardent opponents of new wars. Basic human empathy makes it difficult to see the point in a dozen or more people dying over a clump of trees even when the reality of battlefield life makes patches of real estate incredibly valuable.

Of course, this video also offers quite a bit of information about why Russia’s army is doing so badly in Ukraine. It is more or less a documentary in how officers far from the action send people to die for no reason but to tell their superiors they mounted an attack in their sector as ordered by their own superiors.

To sum up: A Russian squad likely dispatched to locate Ukrainian fighting positions either as a probe or ahead of a larger attack is all but wiped out on camera despite having a clear advantage in numbers. Incredibly, most of the soldiers try to attack over mostly open ground, only clumps of dead grass to use for cover.

Not only that, but they are doing this without any apparent support from tanks or infantry fighting vehicles. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian troops in the trench are able to fire a few shots to keep the Russians from getting too close too fast while the drone operators relay the results of shots fired by distant artillery guns to walk subsequent shots ever closer to the target in an astonishing display of precision.

The sound in the video is almost certainly not native to the fight, though a drone at altitude isn’t going to be able to record and reproduce the actual sounds of battle as the soldiers experience them, so I could be wrong. Music definitely doesn’t play in the background on most battlefields, though, so a foley artist has been at work.

But aside from that and some natural editing to focus on when things are actually happening, this video appears to be entirely legit. Apparently shot somewhere north of the Bakhmut sector, it shows the kind of landscape soldiers have been dealing with over the past winter outside of urban areas.

In a few weeks all those trees will be blooming, offering added cover to anyone underneath, which might alter the dynamics of the conflict at the local level, though in which direction I am not yet sure. Both attacker and defender in a given situation want to control cover, but the context is everything.

Anyway, the best explanations I have for Russian soldiers not sticking closer to the tree line in the video as they advance are either that Ukrainian troops have mined the heck out of it or another Russian element was trying to slip through to outflank the Ukrainian trench. There does appear to be a firefight off to one side of the Ukrainian trench that might reflect this kind of move, but it seems to have been defeated - likely because behind the camera are more Ukrainian positions supporting the trench the Russian wanted to assault.

Whatever the case, fire support from several different types of artillery slowly wipe out the Russians, who neither retreat nor receive reinforcements. No armored vehicles are anywhere in sight, and these would have been able to offer heavy fire support to help keep the Ukrainian troops from shooting back.

While you can’t read too much into a single video, this engagement tracks with reports from POWs that have made it into the news over the past year indicating that new Russian recruits are treated like dirt, their officers largely ordering them to go forward to make it look like they’re keeping up the pressure all along the front. It adds credence to the view that Russia is trading lives simply to stay in the fight, forcing Ukraine to suffer a steep cost for holding onto territory Moscow has annexed.

Such disregard for the survival of front line troops also demonstrates why Russia’s winter offensive has failed.

Over the past six to eight weeks, Russian forces have clearly tried to press a major assault to the degree they could, focusing attacks along four narrow sections of the thousand-kilometer front line. Their objective might have been a simple advance to the borders of Donbas as publicly stated, or, as I suspect, this fighting in Donbas could well have been intended as a prelude to a major extension of the front near Kharkiv that would come after Ukrainian forces were sufficiently ground down but before Spring made rapid ground movements harder and Ukraine received modern armored vehicles from its partners.

Regardless, the window for that is now over and Russia has precious little to show for it, whatever Moscow’s plans were.

Only in Avdiivka and Bakhmut have Russian forces come close to encircling even a few front-line brigades, to say nothing of creating a deeper breach of the Ukrainian front. In exchange Russia has probably suffered between 40,000 and 60,000 casualties since January, though admittedly half or more of these were Wagner forces the Russian military cares little about, preferring Wagner waste itself on frontal assaults instead of committing Russian troops.

Conscripts from occupied parts of Ukraine press-ganged into service appear to be fulfilling a similar role in Avdiivka and Marinka, further south. Followed by better trained and equipped airborne units acting as shock troops and forced to stay on the front by Soviet-style “blocking units” with orders to shoot retreating soldiers, these formations are basically meat shields intended to keep Moscow and St. Petersburg Russians from suffering high casualty rates while the war drags on.

I suspect that Russia has in fact built up a strategic reserve capable of inflicting major damage on Ukraine if fully committed, however using it is now very risky. If Putin’s forces strike deep behind Ukrainian lines then bog down, Ukraine could surround and defeat a major Russian force and take thousands of prisoners, a situation that Putin might well find politically unsustainable.

A big part of the reason why the fighting in Ukraine has turned into what people think of as World War One style trench warfare may be less a function of Russian incompetence and more a revelation of new realities of warfare that most existing military leaders are utterly unprepared for. No one wanted the First World War to drag on like it did - trench warfare was an innovation that defied expectations across the board and transformed what was supposed to be a highly mobile conflict into one of static attrition.

A big part of the reason? Technology changed some of the basic variables in the basic equation of warfare.

To actually lay these out in full detail would be a treatise unto itself. To understand what I’m getting at, it’s worth taking a brief look at the history of warfare in a grand sense.

War is a contest over resources, with each side trying to control vital territory by investing its power across the landscape in a physical sense. Combatants muster combat power in the form of people, equipment, and supplies and apply it with some level of efficiency to achieve specific objectives.

The violence of warfare tends to scale with technology, which also shapes the contours of the fighting because to apply tech effectively requires organization, implying long-term investments in things like training. Military organizations of any size are constantly dealing with limitations imposed by both present difficulties and prior assumptions about what those were going to be.

Which is all a complicated way of saying that war involves making bets and suffering consequences when these are made using poor information. A country that decides the correct way to fight a war is to have a fearless leader lay out in precise detail what their subordinates will do at all times, creating a perfect master plan to govern their actions, will naturally find it difficult to deal with an opponent who embraces pure chaos as a strategy.

Warfare is all about creating and taking advantage of power imbalances. Smart warfare tries to leverage these systematically to cause the opponent’s entire architecture of resistance to collapse, as happened to Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War - or Russia’s march on Kyiv in 2022.

In the old days, combat power was delivered almost entirely through biological power - the muscular energy produced by humans and horses. This was generally best delivered in the form of dense crowds of soldiers physically battering each other until one side or the other broke, got surrounded, or simply ran out of troops, with projectiles from arrows and slings adding to the violence.

But once humans worked out how to make things explode and do so reliably, dense groups of people suddenly became vulnerable, even if on horseback. Figuring out how to make bullets fly out of a gun repeatedly, instead of making shooters reload after every shot, as well as making them spin in flight ensured that a single small team could threaten dozens or hundreds of enemy soldiers from a safe distance.

All of a sudden the maximum lethal range of the average military unit’s weapons expanded, and with it, the amount of territory a given soldier could theoretically control. Instead of needing thousands of people standing shoulder to shoulder to win a big fight, they could be widely spread out and still able to literally reach out and touch their enemies without even having to be in shouting distance.

This changed everything about how armies fought at the local level, which forced line officers to re-think how they led their troops in operations and general officers to work out new strategies to use their divisions.

Except, instead of doing it ahead of time, it took the total collapse of an old paradigm of warfare across four years from 1914-1918 to make leaders accept that the old ways were dead and gone. Four years and hundreds of thousands of lives, a bloodletting that shook the foundations of every European country to its core and began the belated demise of Europe’s colonial empires.

Officers promoted by other officers who believed that the proper use of soldiers was to attack at any cost created a military culture totally divorced from scientific realities of the day. After the war, most of them then overcompensated in the other direction, taking the tactics they developed to finally break the deadlock of the trenches to a new level.

Most histories of the Second World War describe it as being dramatically different, but this, in a perfect mirror of what happened after World War One, is a misleading read of the true dynamics. First off, the idea of the fighting in 1914-1918 being totally static is derived mainly from the British and French experience of the conflict, with America joining in at the tail end.

In keeping with the myth that German aggression was solely responsible for World War One - in truth, both sides were brutal colonial empires doomed to self-destruct in a major war sooner or later - people in the English speaking world are not generally told that the Western Front was secondary for Germany after its initial push towards Paris failed in 1914. Germany was on the defensive across the Western Front for the most part until 1918, and even then kept around a million soldiers on occupation duty in the conquered East, creating ex-soldiers after the war who couldn’t understand why Germany sought an Armistice when it did.

While Germany absorbed one ill-conceived and poorly-led French and British ground assault after another, it was busy propping up Austria-Hungary’s own two-front war against Italy and Russia. Soon, the entire war effort was being run from Berlin thanks to the fading Habsburg Empire’s dysfunction. And the fighting on the Eastern Front throughout was far more mobile and dynamic than anything witnessed in Verdun, at the Somme, or along the Marne.

Similarly, the Second World War had its fair share of attritional trench warfare too, and not just in Stalingrad. In fact, the myth of the German blitzkrieg was an explanation first floated in the US media for the incredible collapse of the British and French armies in 1940. Truth be told, Germany only tried a slight variation of the plan it had used in 1914, the difference being that after duping the Allies into committing their main forces in Belgium the Germans conducted a massive end run through the Ardennes in what amounted to an epic cavalry raid through a sector of the front the Allies thought was sufficiently well guarded.

An explanation was required to explain the Allies’ pitiful military performance and shocking defeat in the Battle of France, which could have jeopardized American military aid just as any Ukrainian defeat would today. Some American journalists coined the phrase blitzkrieg to contrast France’s sudden collapse with the six-plus months of inaction on the ground that had defined the Western Front. This was soon invested with new meaning by British and American leaders, who claimed that Germany had invented an entirely new way of war - one German generals like Heinz Guderian were more than happy to latch onto down the line to secure a twisted kind of legacy apart from their support for Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Fact was, even the best German tanks in 1940 were generally inferior to their French and British counterparts, a single model sometimes holding up the advance of a couple dozen German tanks for hours. The typical German take of the time was equipped with the same kind of weapon used on today’s Bradley armored vehicle, essentially an over-sized machine gun incapable of harming most tanks. Not only that, German anti-tank gunners were primarily equipped with what they referred to as “door-knockers,” a 37mm cannon that couldn’t beat any modern heavy tanks fielded by any of Germany’s enemies. That’s why Germany’s famous eighty-eights got that way - they were a heavy anti-aircraft gun the German ground forces turned to in desperation.

What Germany in fact had going for it was not its tanks but the combination of multiple kinds of vehicles equipped with a fancy new device called a radio.

This allowed outclassed German tanks the ability to work around any threat they couldn’t take on their own, with the infantry and artillery units they traveled with deploying to handle fixed targets while the tanks and armored cars roamed around looking for targets of opportunity nearby, especially enemy trucks or infantry in reserve not expecting to see tanks of any size appear outside their tent. Aircraft were assigned to be on call at all times to ward off French or British aircraft or dive bomb hostile tanks or artillery spotted in the area.

These tactics were not new - they had all been developed by the end of the First World War. The radio, which Germany adopted earlier and with greater enthusiasm than its rivals, allowed decentralized groups to more effectively coordinate, giving German forces the ability to control or at least impact an even larger area than explosives and machine guns allowed. Germany also had a unique doctrine allowing for an almost extreme level of insubordination by anyone who knew their orders were outdated.

But their techniques - even, though imperfectly, this innovation-tolerant leadership style - were soon adopted, and by the end of the Second World War trenches and attrition were the order of the day once again, this time on the vast Eastern Front stretching from the Baltic to the Black Seas. Once the technological gap had been bridged, the laws of war took hold, and the ability of small groups of people to leverage firepower allowed Germany to survive one Red Army onslaught after another for two full years after Stalingrad.

The Soviet Union could never work out decentralized operations, but did have the ability to keep throwing bodies and metal at the German lines. Which could never be strong everywhere, and slowly gave way - breaking catastrophically in many cases. Germany inflicted extreme casualties on Russian forces in battle after battle, but were ground down and forced back, the constant partisan warfare hitting their supply lines only adding to the Germans’ challenges.

In both World Wars the reality on the ground was far more complex than commonly acknowledged. Trench warfare and mobile warfare each have their place and time, because warfare is all about constant evolution - no paradigm lasts forever, often not even for very long.

Sometimes it just takes a long time for the message to get through. Consider how many countries have tried to wage counterinsurgencies over the past hundred years and almost always failed.

Laws of war do exist, but that doesn’t mean powerful people pay close attention to them. Which is, of course, how they become less powerful over time - Vladmir Putin is an epic case in point.

The past year of fighting in Ukraine has demonstrated that the combination of widespread networked sensors and GPS-guided precision munitions has done the same thing to warfare in this century that machine guns and fused artillery did in the last one.

It is now almost impossible to hide on the modern battlefield once out of cover, and once detected a strike from some distant artillery piece, rocket, or jet can come in a matter of minutes.

Small units deeply entrenched in favorable conditions and backed with sufficient firepower are extremely hard to displace. At the same time, mobility is badly constrained by the variety of explosive devices that can be deployed in all kinds of creatively nasty ways.

Russia’s army, broadly speaking, has not been transformed to the degree many US-based experts insisted it had before 2022. It remains, in terms of how it treats personnel and the style of equipment it fields, oriented towards defending fixed locations until an enemy is exhausted, creating space for a swift and sharp counterattack.

But because of the vulnerability of Russian tanks, which are smaller than European or American models in order to be cheaper and easier to maintain, going on the attack is extremely difficult. Russian designed infantry fighting vehicles don’t have enough armor to survive ambushes launched even by light infantry, much less artillery, so can’t get soldiers through hostile artillery bombardments to seize a target position.

This has forced Russia to revert to infantry-heavy tactics relying on guys essentially sent in as human sacrifices to allow better trained troops with longer-range weapons to plaster a target from a distance. Which in turn makes Russian forces highly dependent on a steady supply of ammunition that is always going to be a priority target for an opponent.

But even more than that, the Russian military system remains extremely rigid. If officers are killed or otherwise separated from their soldiers, these are likely to do nothing but protect themselves as best as they can. They’re not, on average, liable to innovate their way out of a situation and might even be prone to surrender if surrounded for any length of time.

Which means that if and when Ukraine fields enough modern armored vehicles backed by appropriate levels of air power and artillery support, it can launch some serious offensives to drive back the Russian invaders. The longer the Russian army pursues an attrition strategy, the more brittle it will become. That could mean a 1991 Iraq-style collapse along one or more sectors of the front later this year.

Ukraine’s authorities are starting to worry that too much attention being paid to its upcoming counteroffensives are a security threat, but this fear is misplaced.

The best possible thing that could happen over the next two to three months is a sense of resigned inevitability setting in on the Russian side. Unless reports of how badly Russian soldiers are feeling about conditions are dramatically over-stated, the reality of being used as they are will make them prone to giving up in large numbers if they are surrounded and feel that they are safe from their senior commanders.

Ukraine isn’t going to achieve the kind of battlefield surprise required for a counteroffensive to succeed according to the traditional sense of the term. Like 1991, knowing the fact that Ukraine is planning an attack along a single narrow front, if that is what Kyiv chooses, won’t spare Moscow from the hard choice of figuring out where it will fall - or how to actually stop it once it’s in progress given its troops battlefield vulnerabilities.

Most likely, Ukraine will strike for the Sea of Azov because success will force all Russian units in occupied Kherson and Crimea to be supplied across the Kerch Strait Bridge, which will be vulnerable the moment Ukraine secures any part of the Azov coast - possibly even the highlands a few dozen kilometers north. But the exact avenues of attack will be impossible to predict in advance, and the more Russian generals think themselves into a tizzy debating which is best the better.

I plan to add some myself in the near future. If Russia wants to prepare for them all, more power to Moscow. All it will do is make itself vulnerable everywhere.

Once the operation begins, facts on the ground will change so quickly the specifics of where Ukrainian units strike and how hard won’t be possible to know far in advance. Surprise in the modern sense has to be rooted not in the enemy failing to guess your broader plan, but in their inability to do anything about it once it starts to unfold.

This is why Ukraine getting every kind of modern equipment it is asking for, including combat jets, is vital. The lead time on the latter means the committment to begin training has to happen pretty much right now.

In truth, though Ukraine will probably begin some counterattacks in the near future along sectors of the front like Bakhmut and Avdiivka where Russian forces appear to be at risk of becoming over-extended, the big one backers of Ukraine are waiting for might not start until late summer.

Some shocks are best delivered all at once, when the opponent is so weary of waiting they aren’t truly ready when it finally arrives.

My overall forecast for spring is that Russia will spend the next two months or so grinding forward to try and pre-empt some of the power of Ukraine’s much-touted counteroffensive, whenever it comes. Whatever attacks it launches will be primarily intended to spoil Ukraine’s preparations and deflect its efforts, maybe seize a political victory or two.

Border attacks remain very possible, however, and there seem to be some thoughts in that direction from the Russian side, given some recent propaganda about the vulnerability of Belgorod. A buffer zone near the border is an option Putin might pursue to distract Ukraine further.

Putin’s best hope is that aid to Ukraine from the US and NATO has peaked, with the upcoming US elections heralding a major shift in American focus. Once Ukraine has burned through its shiny new Western toys, diminished aid and sustained Russian pressure over the next 1-3 years will give Putin - or so he likely hopes - a shot at going big again with substantially more success the second time around.

Ukraine, meanwhile will likely have to launch local-scale counterattacks to cut off advancing Russian spearheads near Avdiivka and Bakhmut. Yet Kyiv will have to do this without relying on modern gear and the 9-12 new brigades equipped with NATO-trained troops being stood up now.

Those will have to be reserved for the big pushes to come. The ones that, if all goes well, stand a real chance of ending this war once and for all.