Ukraine And The Crumbling World System

The Adaptive Cycle is a useful model for understanding relationships between countries; unfortunately, applying it warns of a turbulent decade ahead.

Warning: Long, esoteric piece ahead! I try to keep things as jargon free and approachable as possible, but this is a brief outline of a theory of international relations I’ve been developing on and off again for about twenty years now.

In short, this essay offers an outline of what you might call a systems theory of international affairs. The question of why powers rise and fall is ancient, and in my own private studies I’ve created a synthesis paradigm that bridges the schools often termed realism, idealism, and constructivism.

I’ll actually open up the comments section to see what folks think. A kind of public peer-review, you might call it, though I can’t guarantee I’ll reply - I’m not great at following comment threads in real time.

Anyway all science ought to offer useful answers to someone, and my writing about Ukraine is motivated not only by personal affinity for the country’s struggle but because my read of the evidence makes me certain that there is no better option. Sometimes, to bring lasting peace you have to win a hard war first.

International Relations As A Complex Adaptive System

According to the dominant strands of thought prevalent when I was studying international relations as an undergrad in California twenty years ago, the Ukraine War - a conflict in the heart of Europe - should never have happened.

The End of History theory proposed by Francis Fukuyama held that the fall of the USSR heralded the lasting triumph of what many scholars like to call “Western Liberal Democracy” or something to that effect. Historical progress had reached an apex: now the US-led world order would secure peace and prosperity for all in a grand Pax Americana rooted in free markets for everyone - whether they liked it or not.

The leading competitor to this theory was Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations concept. It broke the world into cultural regions he claimed had ancient roots and were bound to fight because each professed intrinsically incompatible views about moral life. Russia, for the record, was - as is rightful - considered by most scholars to be part of the “Western World,” as proponents of the idea call it.

These were not the only paradigms out there, but they got the most attention from public-facing scholars and wound up influencing US foreign policy in destructive ways. The rot remains, too: unfortunately, academia is no less prone to fads than any other industry, and fields like history, politics, and economics are littered with examples of failed paradigms that stick around long past their sell-by date. Policy all too often suffers, which means misallocated resources and, too often, a death toll.

Most disasters are predictable and often even predicted well in advance. Major earthquakes are a fantastic example: at some point this century the entire Pacific Northwest is likely to experience a massive, Japan-style earthquake and tsunami that will kill thousands of people and lead to trillions in economic losses. Much could be done to dramatically mitigate the toll, but is this an issue anyone talks about in the US federal government?

Nah - and it isn’t just civilian infrastructure at risk: one of the biggest base complexes hosting nuclear weapons is just outside Seattle. When Cascadia’s subduction zone goes, a big chunk of the US nuclear deterrent probably goes with it - not explosively, of course, but once the infrastructure required to get missiles and warheads onto submarines is toast, that’s an effective mission kill, as military types put it.

Time and time again, especially when powerful people are involved, esteemed experts fail to see a catastrophe coming that ordinary people in retrospect all recognize as being obvious and inevitable. The nuclear meltdown at Fukushima was one such incident. With respect to international affairs, the length and ferocity of the First World War counts as another. So too the Second - and the later fall of the Soviet Union. Kyiv not falling in three days, like the Biden Administration was certain would happen in the winter of 2022, represents a poignant contemporary example.

There are some very simple reasons for this pattern of repeated failure that anyone who has read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions should recognize. Science is done by people, who tend to form clubs - especially when their careers are on the line.

That is why the world lacks a coherent, properly scientific understanding of how the world works at the highest level, where the regimes that control countries interact and do battle over abstract ideas like their security. Ideologies like nationalism, liberalism, socialism, capitalism, and all the rest will each insist that their paradigm is the only true one, imitating the messianic faith systems they grew from. But the lack of a unified theory of international relations allows scholars steeped in the paradigm of their choice to act as if they have a level of understanding that their real-world policy prescriptions usually demonstrate is lacking.

Most international relations theory that escapes the confines of the ivory tower is essentially a limited application of philosophy backed by a selective reading of the historical evidence. Bias is embedded into each dominant paradigm, making it impossible to generate effective policy.

It is impossible to produce purely objective, totally unbiased science. There is always some skew, but the best sciences produce reliable explanations about the world, with reliability being something that can be measured. Bridges constructed a certain way stand the test of time while others don’t. Aircraft that are built poorly fall out of the sky.

To identify the vital patterns that animate countries requires taking a complex adaptive systems approach. This means building models of interaction that leave each country as many degrees of freedom as possible - in short, presuming the minimum about what it must do to persist. With just a few parameters of interest a vast array of unique behaviors can be observed as a simulation plays out, and statistical analysis of outcomes can reveal why a system evolved the way it did.

This might sound complicated, but with the right training and user interface working with this type of information becomes intuitive. In truth, the human mind operates as a complex adaptive system focused on extracting real-world meaning from a small amount of information. As we grow up, we train our mind to get better and better at this until we perform actions no robot can yet mimic without even thinking - language is actually one of the easier human activities for a robot to decode because the rules of speech are more rigid than most aspects of day-to-day life.

Lack of a simple, straightforward, yet holistic theory covering relations between countries as they evolve over time is the main reason why so few people fully appreciate just how big a deal the Ukraine War is. Like clashing tectonic plates, powerful countries periodically enter into periods of intense hostility that dramatically alter how every other country in the world thinks about their future, which causes them to act differently than they did before.

The impacts of these grand shifts can be so stupendous that the lives of ordinary people are upended everywhere. When Putin unleashed his full-scale genocidal assault - that’s what invading a country with the intent to absorb its land and kill its intellectual and political leaders is - prices for food and fuel skyrocketed across the globe. The instability this has seeded will almost certainly cause more shocks in the near future.

As ancient myths from many cultures have noted for millennia, the old world will always die and be reborn at some point. Ragnarok, Apocalypse, the Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma, Mayan and other indigenous calendars: the pattern shows up over and over.

Systems, as Niklas Luhmann argued, are real. Even though they cannot be reduced to their base elements like a simple machine, that’s just a function of our inability to see inside without disturbing its operations. Often, in science, you can’t observe something without becoming part of the experiment: and experiments themselves are artificial, all factors never fully and completely controlled.

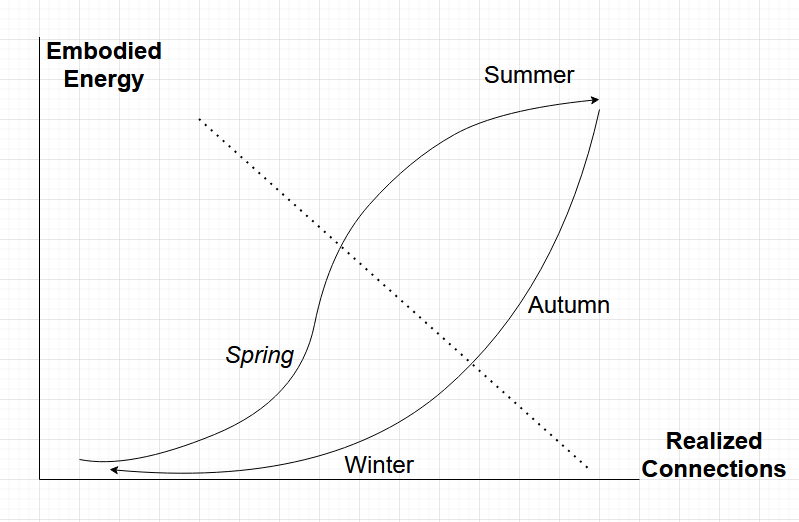

Like all complex adaptive systems composed of independent agents, the world system goes through seasonal cycles. These may be caused by external factors like a disaster, plague, or climate shift, but just as often they are produced by internal forces: a combination of too many elements crashing at the same time that creates a cascade failure.

In school most of us are taught to see wars as distinct events with start and end dates. But a better way to look at them are mode shift between countries: instead of coexisting or at least refraining from open hostilities, something drives one or more to escalate to general violence. This can, in the worst cases, take the form of genocide: an effort to annihilate opposition permanently.

Wars have a tendency to spread these days because they destabilize the entire interdependent global system. Even as independent agents, countries are prone to herd behavior: rather than respond in a linear way to change they tend to mode flip and act according to a different set of rules. Too many doing this at once can bring down what order was produced in prior years in a consuming fire that burns until no one is able to fight any more.

What’s key to remember is that countries, because of their size, are always steered by a regime. Being a group of people who tend to develop their own identity and sense of collective interest, it is all too easy for regime members to come to think of their interests as equivalent to those of the rest of their country. When having power allows a group to amass more and entrench themselves in positions where they are more easily able to exert control over the regime than ordinary people, problems are inevitable.

Ultimately regimes come to see themselves as locked in competition with both rivals abroad as well as at home over control of vital resources. To maintain power in one domain often requires taking action in another, and strange alliances can form that defy conventional international relations approaches.

A complex adaptive systems approach can show why this happens and give a sense of how best to manage a country’s affairs to mitigate the seasonal shifts. It also warns against the dangerous idea held by a lot of people in power that the clock can either be rolled back or frozen in place: that’s called a rigidity trap, and involves wasting resources trying to hold back the tide.

The only way out is through: managing a complex system is like navigating in a storm. Fighting some currents is a futile waste; riding others gets the ship to port intact. Different phases require different approaches, and it is essential to always be planning two seasons ahead and actively preparing for the next. That’s how you build and maintain adaptive capacity, which is the key to thriving despite the season.

The Ukraine War is not a “Clash of Civilizations” or struggle between democracy and autocracy, but something far more grim than either. It represents a deliberate effort by one country to exterminate the other because its own internal complex adaptive cycle is entering a period of collapse, driving Putin’s regime to try and reboot the entire world system to his liking out of desperation.

It won’t work. It never works. Would-be European emperors since Caesar have chased this vainglorious fantasy and failed. What do the Thirty Years War, Napoleonic Wars, First and Second World Wars, and Putin’s assault on Ukraine have in common? All were regime-instigated conflicts driven as much by domestic concerns as real international security issues. Each dragged the entire planet into a series of brutally violent conflicts defined by how European leaders in powerful countries perceived the shifting balance of power at home and abroad.

Countries And Narratives

Countries are best defined as places where people who share a set of common values live together in some kind of predictable order. Democracy, autocracy, theocracy, and every other flavor of government is a different realized solution to the same basic problem of keeping people organized.

Democracy is the least bad system, as Churchill put it, because it forces churn on regimes: individuals can’t, at least in a healthy democracy, remain in power indefinitely or pass it on to other family members. Any democracy can fail or become corrupted, but separation of powers and respect for people’s individual and collective autonomy hedge against this threat.

In any social system as large as a country, sub-groups and localities will express their own distinct flavor. Diversity is a strength, a root of adaptive capacity, but it does not come without costs. the larger a country gets, the more complex governing it becomes, and the more likely it is that a sub-group will emerge that sees itself as guiding or leading all the others on behalf of all.

To sustain a country requires a common narrative about what it is and why it exists that most people who deal with it can appreciate. This narrative is never fixed; how it changes is a matter of great importance to any group who comes to control how their country behaves on the international scene.

People are innately attracted to narrative: telling stories is the oldest form of science communication in the world. Elders in the past would serve as guardians of vital lore while those more able to gather and hunt did that essential work. Their added experience granted them perspective others lack, including the sorts of mistakes to avoid.

So it is only natural that leaders of countries and the close-knit clubs that dominate politics in many countries whatever their system of government take care to influence public narratives whenever possible. Every regime around the world sends spokespeople out into the world to proclaim how true they are to whatever story the regime has invested in.

Whenever a country goes to war, this represents a choice by at least one group of powerful elites to sacrifice other people’s lives for some purported benefit. History shows that in most cases they see as much potential for gain domestically as they do in the endless power struggle between countries.

In periods of crisis and general uncertainty, powerful leaders in stagnating or failing countries are extremely prone to fragmenting their own society or even the entire world in an effort to take control of as many vital resources as they can ahead of the winter they sense is ahead. Vladimir Putin’s empire is an absolutely classic case of this tendency turned utterly pathological, Nazi Germany reborn.

Countries transform themselves into empires by trying to expand their borders and take control of new territories and peoples, subjugating these to the national narrative in ways that usually leaves them as second-class citizens - or worse. Predatory regimes always have some excuse, whether divine right, economic necessity, helping people perceived as fellow countrymen who happen to live in another land, or some other reason to exercise their power. But the end result is always the same: a distinct pathway of rise, stagnation, fall, and dissolution. The more vicious the wars involved, the more rapid the fall.

Countries have to be able to defend themselves and minor wars, border skirmishes and the like, are a regrettable feature of international life. However, it is important to keep in mind that throughout history open warfare has in fact been the general exception, not the rule, in human affairs. When you look at all the country to country relationships that have ever existed it’s frankly shocking how infrequently any of them fight to the death even if their relationship is historically poor.

The rarest and worse kind of war is one of genocide. Choosing to commit genocide represents a malignancy of social order within a country that causes it to see everyone in its neighborhood, if not the entire world, as a latent threat with one long-term answer: extermination.

Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union are only the two most egregious examples, the modern standards to compare all other tyranny by. Yet as impossible as it seems, Putin’s Muscovite Empire is the twisted child of both.

When two empires go to war, they learn from each other. In the dance of adaptive cycles they tend to absorb the most effective techniques of the hated into themselves. Contrary to Hegelian dialectics, thesis and antithesis do not synthesize: each absorbs a core of the other, Yin-Yang style, and transforms into a new strain to carry on the struggle.

Why? Because it is people doing the fighting on behalf of regimes. And for the powerful, who don’t personally suffer like ordinary folk, the struggle can easily become an end unto itself.

Think about how even people who become billionaires usually keep on trying to amass wealth, despite not strictly needing to be kept exceptionally comfortable for the rest of their natural lives. People are always afraid of losing what they have, which drives them to seek more. Nobles and paupers are cut from identical cloth; one simply has access to more resources and can make enough people fight to trigger that general state of chaos called open war.

The Ukraine War represents an extremely significant foreshock ahead of a global rupture that could reach the level of 1914-1945: the First and Second really being just one long World War with a brief interlude of varying length, depending on where you happened to live. China and Japan were at war by the early 1930s; it took the USA until the end of 1941 to become formally involved.

In this epic global collapse, Europe’s colonial empires destroyed themselves across two generations of horrific and largely pointless conflicts that all fed into each other until everyone lost. The USA’s century of leading the “Western World” in economic and military terms has primarily been a function of being the sole undamaged manufacturing bastion left in the world.

Moscow’s empire today is the remnant of the last traditional European empire left standing; its victory over Nazi Germany was almost wholly pyrrhic, the Soviet empire that emerged to dominate Eastern Europe and much of Central Asia was fatally bound to heavy military industry and raw materials exports. While the USA is also technically an empire with a history of ruthless genocide and violent extraction of resources from the poor by the wealthy, its character was different: while regime change and coups were fair game, direct occupation was rarely attempted. When it was, the US got burned.

Putin’s empire is one in the classic Greco-Roman mold: hence his insistence that his Rome is different, ancestrally bound to Byzantium as opposed to Rome. But the two halves of the empire were cut from the same cloth, and a notable characteristic of every European empire and their imitations has been an attempt to claim descent from ancient Greece and Rome.

The expansion of Imperial Russia from being the Mongol-dominated city-state of Moscow into a monster stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific was identical in nature to the centuries-long assault on the rest of the planet by the other European powers. In origin, language, and religion all the various flavors of Muscovite Empire across the past four centuries have been identical: ruthless exploitation of the weak for the benefit of the wealthy core, the bear changing colors but never altering its essence as a predatory pyramid scheme pretending to be a national identity.

Whenever the core runs short of victims in one fallen country, it moves on to seize another. To sustain this kind of imperial regime requires endless growth to acquire new resources. Its beneficiaries latch on to a self-serving story about their innate greatness and right to rule, pretending that even the enslaved survivors ought to be grateful to have been brought into the light of civilization.

As European colonizers destroyed the fabric of life in the pre-contact Americas and later on in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, so did the USA treat the peoples it met on the Manifest Destiny inspired march to the Pacific. Moscow’s empires have done the same to the peoples surrounding the territory they have already decimated for hundreds of years. Eastern Europe broke free from Moscow’s power in the 1980s and 1990s, but Putin never forgot that he once walked as master in Warsaw, Prague, and East Berlin.

The Nature Of Moscow’s Empire

Putin is in fact waging a war against the entire world just like the one Hitler launched and for the same basic reason: imperialism. His regime has committed to maintaining control over its people by embracing a narrative about the inherent superiority of a mythical Russian World over the decadent rest, with some areas more tolerated than others - for as long as it is convenient.

To stay in power as his country is progressively hollowed out and looted by the gaggle of oligarchs and religious officials who underwrite his regime, Putin has chosen to initiate a kind of revolution that seeks to unite all the fake traditionalist factions in Europe and the Anglosphere against the rest. Though the active fighting in this conflict has so far been mostly restricted to Ukraine, that is only because Kyiv did not fall on schedule.

He’ll never give up trying to take it now. He can’t, even if he pretends to be satisfied with what his forces have clung to since 2022.

To survive, Putin has to foster a world of warring ethnic enclaves who will exploit their own people and the planet until both are drained of life. It’s a self-conscious effort to build a hybrid of 1984 mated with a religious variant of Brave New World’s joy-focused society.

Instead of joy induced by drugs, instead good ruscist citizens are meant to enthrall themselves with the alleged achievements of their grand civilization even as the last remnants crumble around them. Putinism is a messianic death cult fully aware that it has no longevity but bent on dragging as many people and places down with it as possible.

Nazi Germany was exactly the same: lacking the ability to exploit colonies in Africa and Asia as its geopolitical rivals could, it tried to transform Eastern Europe into a version of the American West by embracing the genocide of all ethnic groups the Nazis saw as lesser than themselves - which was nearly everyone. Ethno-nationalist empires rooted in a perversion of Christianity can’t tolerate the existence of anything that might threaten them. They embrace a paranoid mode of faith that must always produce an enemy to fight abroad to sustain the domestic delusion keeping the regime in power.

Moscow isn’t the capitol of a normal country anymore. It’s the heart of a cult that sincerely believes it has a divine right to speak for a linguistic group whose members are spread across the globe. Based on Putin’s ideology, even places like the US West Coast are in Moscow’s natural orbit because Moscow’s explorers once had bases here. In the state of Oregon, where I live, thousands of Old Believers who fled Moscow’s tyranny long ago are, in Moscow’s eyes, citizens it has a right to use force to control.

You aren’t hearing this from the Biden Administration or even its Republican opposition because almost no one in a a position of power in the USA wants to believe the truth: Putin is both rational and quite mad. He will take logical, concrete steps towards material goals despite the rest of us knowing they are utter fantasies- not unlike a serial killer.

Putin’s warped ideology ignores the true heritage of his regime, creating a false history that conveniently begins the story when the first proto-Tsars in the Principality of Muscovy started subjugating rivals. Moscow was a city state that first became prominent centuries after the Mongol annihilation of the Kyivan Rus, nearly a thousand years ago. This was a cosmopolitan alliance of tribal cultures and trading centers connecting Scandinavia to the Middle East, apparently emerging from a series of unions between wealthy Norse Viking clans and leading families among the local peoples they came into contact with while mounting trading expeditions to Byzantine Constantinople.

Originally one of the many border tributaries created by the Mongols to manage their vast empire, Muscovy’s leaders wound up absorbing the older country of Novgorod to the north and expanding east after the Mongol empire dissolved. Once powerful enough, it began to advance to the west, deeper into Europe, where it ran into other peoples who traced their ancestry to the Kyivan Rus period.

Moscow also pressed south towards the Ottoman domains, taking over the Caucasus and the steppes between the Don and Dnipro rivers as well as Crimea, an ancient trading post. The Cossack peoples in this region were descendants of the steppe societies that predated the Mongols and fiercely independent, though many were ultimately swayed to Moscow’s side, becoming its fiercest soldiers.

Other parts of Ukraine, including the Kyiv area, were like many regions in Europe passed between different dynasties. But though disunited, much like Poland for a great deal of its history Ukraine is one of those vast countries defined by its geography - as well as the memory of other people coming in and forcing the locals to defend what they have. As much a network of villages and family groups sharing a common trade language as a country in the classic sense, the bones of modern Ukraine are apparent in the historical record despite its lack of an independent monarchy the same as modern Germany is clearly descended from a collection of city-states.

Moscow’s empire, on the other hand, has never not been in flux. One ambitious leader after another has tried to transform it into something coherent, but it has always remained far too large and far-flung an empire to efficiently manage for long, rebellions by indigenous peoples a constant challenge.

Though it has sadly been canceled and is quite raunchy, the black comedy The Great offers an excellent portrayal of how fragile and fundamentally European the empire built by Peter and Catherine has always been. Russia has always been a “civilizing” idea foisted on a wide array of diverse peoples with their own languages and ways. Just like all the other countries of old Europe, its ruling monarchs were the product of arranged political marriages, incoming elites adopting the local cultural patterns while dressing up ideas brought in from abroad as domestic innovations.

Before invading Ukraine Putin published an astonishing historical essay laying out his views on Ukraine. These tell a story of Moscow’s empire arising to unite the so-called “Russian people,” with Ukrainians being deliberately reduced to “little Russians” who have been corrupted by the West, by which he means Roman Catholic and Protestant ways.

This essay was made mandatory reading for members of Putin’s military and goes on to insist that Ukraine doesn’t really exist as a real country and is effectively territory stolen from Moscow by the malevolent West. He also makes a point of equating this to the West using nuclear weapons against the ruscist state, for the record: whatever red lines Putin has regarding these devices were crossed long ago.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise when not only were the atrocities of Bucha and Irpin and so many other places revealed in graphic detail after Ukraine forced the invaders out of the north, but captured documents indicated that occupied Ukraine was to be subjected to outright genocide. Notable people would be killed outright, imprisonment of anyone deemed a political risk was planned, and torture centers were set up in the same basic layout all across the country to create a system for inflicting terror. Collaborators were in place to locate targets, both people and infrastructure - this was premeditated murder, pure and simple.

The plan was virtually identical to what the Soviet Union did across Eastern Europe in the wake of the Second World War. It was also part of the tactical repertoire of the Tsarist Empire. Brutality is how the Russian World stays alive. That, and always finding a new victim: vampires exist, they’re just called empires.

Fortunately for the world, Putin’s invasion instantly transformed Ukraine. A huge, diverse, and highly decentralized country found itself under attack by an enemy that had come for many generations of Ukrainians before. It is fair to say that the modern Ukrainian nation was born in the winter and spring of 2022. Putin achieved the exact opposite of what he and generations of Muscovite rulers have worked so hard to accomplish, up to and including Stalin’s induced famine, the Holomodor.

Now it is absolutely impossible to conquer Ukraine, which spells death for Putin’s empire. If it can’t control Kyiv, the mythological heart of the Russian World, why should Chechnya, Siberia, or even St. Petersburg stay on Moscow’s side at the cost of being cut off from the rest of the planet? If Putin’s empire divided into city states tomorrow, the rush to reinvest in the region would utterly transform local areas from the Pacific to the Black Sea.

Even if Putin mobilized every body of fighting age under his power, he now lacks the equipment to kit them out properly - North Korean stocks are unlikely to be of high quality. And at some point the strain on the economy will tell, even if sanctions have, as anyone who studies the history of sanctions regimes knows, never altered a powerful country’s behavior.

The terminal collapse of the Muscovite Empire that began in the late 1980s was arrested, for a time, by investment coming in from abroad. Two decades of mismanagement are making up for that stolen time.

Yet as doomed as Moscow now is, Ukraine will remain under extreme threat for the foreseeable future. Regime collapse takes time. And there is yet a danger that the Biden Administration will throw Putin the lifeline he needs to survive and recover.

Too many international relations scholars promoting a ceasefire are relying on outdated theories that fail to understand that countries tell stories about themselves that leaders discover are more binding than material pressures like casualties, at least in the short run. Virtually no leader cuts and runs from a war even when it is obvious that the assumptions going in were badly mistaken - as Putin’s were in Ukraine and the Bush Administration’s were in Iraq.

When an empire dedicates itself to expansion, and especially if it resorts to trying to destroy a neighboring country outright, it sends a powerful signal warning of an imminent fall accompanied by unpredictable and potentially extreme behavior. The Muscovite Empire is a malignant cancer that will spread its lethal tendrils wherever it is able until the thing consumes itself.

The postwar order is dead and done: it has collapsed and something new will have to be constructed. That’s what Putin is really after: building the only world where his maladaptive empire can possibly survive.

As for the policy consequences of this sad state of affairs, they are very simple: if Putin’s invasion of Ukraine does not end in outright battlefield defeat and a return to the borders of 1991, this will set a standard that other leaders like him will attempt to emulate in the years to come.

Appeasement is not just trading land for peace. It’s also what Poland’s allies France and the UK did in 1939: too little to take advantage of the incredible opportunity provided by the aggressor’s military being wholly occupied with a stronger-than-expected enemy until it was too late.

Fortunately, this time around there isn’t any need for direct intervention to stop the monster in his tracks, though a limited no-fly zone along NATO-Ukraine border is more than justified given ongoing ruscist strikes nearby. Just committing in detail to a security plan that leaves Ukraine stronger each passing year until it is brought into NATO is required.

The Europe-dominated, colonial world system is almost dead - Moscow’s defeat will be the final nail in the coffin. There is no need for the world to intervene directly - all that is required is moving the military resources built up during the Cold War and its aftermath to Ukraine as swiftly as it can absorb them, without arbitrary limitations.

Once thrown back to the 1991 borders, the Russian World is also over. Its ideology cannot sustain a defeat of this magnitude delivered by “little russians,” no matter how fancy their tools.

Consider that a timely warning to Beijing, a regime that faces the choice of embracing empire by pressing its claims on Taiwan and going down the same dark doomed path as so many empires before - or trying something different.

The Evolving World System

It is fair to say that the European world system self-destructed in the world wars: after came the wave of decolonization that continues to characterize global relations. The Postwar Order that emerged had at its cornerstones the idea that borders fixed during the decolonization process were supposed to be fixed; all recognized states had sovereignty and the right to expect non-interference in domestic affairs.

Obviously this norm has always been shaky, but the invasions of Iraq and Ukraine have killed it entirely. The question now is what rules of the road will emerge: can a leader win new territory at the cost of blood and treasure? Or will enough countries come together to draw a firm line in the sand that says this behavior won’t be allowed?

Yugoslavia’s violent breakup was a warning that history was not dead, only sleeping. Putin’s wars at home against the Chechens then abroad against first Georgia and then Ukraine were a sign that the Muscovite imperial mentality dominant for centuries has not waned. Russia exists solely as a mental construct that Putin’s regime takes care to define in a narrow, dismal way to keep ordinary people from rebelling against it.

Russia doesn’t even exist for all practical purposes: little truly links people in Vladivostok and Rostov-on-Don. That’s why Putin wants to wall his empire off from most of the world - it’s all about keeping his subjects from recognizing that there are other, better options. At least the USA, broken as the federal government might be as it endures its own collapse, has the states to fall back on: if Washington D.C. were taken out by a meteor or invasion of inter-dimensional dinosaurs tomorrow, America and the Constitution would carry on.

States might form their own smaller countries, but they wouldn’t have any reason to go to war: America’s main issue is profit-driven partisanship taking control of the increasingly decrepit machinery of governance. Moscow has centralized power to the point that total fragmentation seems inevitable: Putin has eliminated any fallback position short of military districts or city states doing their own thing when everything comes crashing down.

Putin’s regime is now all about martial sacrifice: when this intersects with angry veterans returning from a botched war, watch out, Moscow. This has generally what triggered regime collapse in Muscovite empires past.

Any system involving people will ride or die on a small set of propositions that most people agree are true. When they don’t, the system collapses and reorders itself in some way. This can be a true rebirth… or final death.

Nazi Germany isn’t around any more. Nor is Imperial Japan. The British Empire lives on as the Commonwealth. Sometimes France acts like it still has colonies in Africa, but for the most part it realizes it can’t dictate affairs to anyone. The USA might not be so united in about eighteen months the way rhetoric is escalating.

Change is inevitable. Failing to accept and plan for it is what leads to disasters, including geopolitical kabooms most people before will adamantly insist are impossible.

Perhaps the most significant assumption that held starting in the mid 1940s was that the USA would never sit by like it did in the 1930s and watch the international system deteriorate until it got dragged in too. The USA would intervene where appropriate to promote stability and deter any conflict that could lead to a nuclear exchange.

Deterrence means making sure the other side knows that you won’t stand for aggression, even if that risks serious costs. The US-led coalition that liberated Kuwait from Iraq in 1991 was motivated by the simple idea that borders had to be respected and one country didn’t get to remove another from the map. Yes, the US badly damaged this idea in Iraq in 2003, but it did not attempt genocide, however misguided and poorly executed that war might have been.

The entire logic of NATO during the Cold War was predicated on keeping the USA engaged in European affairs as a security guarantor who would prevent Moscow’s empire - the last classic European imperial power left standing after the war - from expanding. Though ideological concerns ended up coloring this basic guarantee, the times when the US made overt moves to prove it would stand up to any major Soviet aggression beyond its borders demonstrated that it understood how the system worked and was willing to fight to keep it intact. That kept Moscow honest.

Refusing to even consider deploying military force to Ukraine ahead of Putin’s invasion marked the death of the myth of American dominance. The Cold War was a terribly fragile peace, of course, filled with brinkmanship and crises and crass betrayals. The US abandoned Eastern Europe to the Soviet sphere of influence while adopting France’s colonial war in Vietnam.

But defending Kuwait demonstrated that, shaky as the Postwar Order was, there were rules. This is why some people insisted that history was over: instead of the world descending into a major conflict as the USSR fell, for the first time ever most countries basically accepted that the USA’s dominance was tolerable. Invading Iraq in 2003 killed that presumption; failing to deter Putin from trying regime change in Ukraine marked the bitter end of the era of American global leadership.

Incredibly, Putin made the exact same mistakes that US leaders did before going into Iraq: underestimating local people’s will to resist. And he also did something else: shred all lingering doubts about his true intentions, demonstrating that he was not just another strongman who could be bought off but a discount version of Stalin who had come to embrace a number of Hitler’s ideas.

It is actions that drive change in international relations: these demonstrate power, and its limits. Putin has proven not only that he cannot be trusted, but that his power is less than his bluffs implied. China won’t see him as a reliable ally from here on out. Biden, meanwhile, has proven that the USA will always find a way to limit its involvement in a fight against a nuclear rival to minimize any risk to itself, allies be damned. All efforts to build alliances in Europe and Asia will be hindered by the largely correct perception that partisanship is making the USA utterly unreliable.

When the two leading powers of the Postwar Era have both defied standing expectations about their mutual behavior, the world system has collapsed. What comes next will depend on whether Ukraine liberates all its territory or Putin shows that by digging in and powering through conquest can pay.

That in turn will have ripple effects across the globe. These will inform actions other countries take at a moment where power is less concentrated than it ever has before.

China is not going to become the new world empire any time soon. If it tries, it will destroy itself. This is the time of the middle powers, who will produce a world system that is best seen as a kind of tapestry.

But whether relations between countries are defined by an expectation that they will squabble over borders and the allegiance of factions in resource-rich countries or shout a lot but mostly avoid bloodshed will be decided in Ukraine. This is one of those exceedingly rare critical moments where decisions made by powerful people today can and will drag the trajectory of history in a better or worse direction.

The desire for peace at any cost is understandable. But just like cutting short a course of antibiotics makes the next round of infection worse, accepting a ceasefire that leaves Putin in control of Ukrainian territory will only do more harm in the long run.

The World System that is emerging today could be characterized as multi-polar, but this doesn’t get at the heart of the complex web of relations at play. I see it as best to look at the global landscape as an ecosystem with players grouped according to the reach of their military and economic power.

Tier One Powers - global interests and capabilities. This group is the closest you come to superpowers in today’s world. They can send military units anywhere on the planet and field nuclear weapons. Each, even China, is internally complex, limiting freedom of action abroad. All have a combined GDP of around $20-30 trillion and $250 billion (China, lowball estimate) to $1 Trillion (USA, inclusive) in annual defense spending.

Europe - Now mostly recovered from the Second World War, the European Union and NATO have apparently tamped down on the continent’s tendency to implode in a major war every 80 or so years. Moscow being the main exception, of course. Strong divides persist between the North (almost part of the Anglosphere, frankly), South, East, and West. North and West are richer but divided on how strongly to oppose Moscow, East and South poorer but similarly split.

China - The People’s Republic ruled from Beijing is infinitely more complex a beast than a lot of scholars are willing to admit. A certain level of bigotry against China is now visible throughout the media in the Anglosphere that makes it difficult to perceive China’s strengths and weaknesses. Primarily focused with securing its near abroad and ensuring that Taiwan doesn’t declare independence, China’s military strength is growing fast, so a shift in approach is required in all domains.

Anglosphere - The USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are slowly drawing closer together (Brexit was a symptom of this), to the point that with the USA’s partisanship-induced decline the whole lot ought to be seen as a collection of about a dozen middle powers with a shared heritage. Deeply concerned about China, internal political tensions in the USA and UK are increasingly leaving Australia and Canada to represent the bloc abroad in everything but supplying weapons to Taiwan and Ukraine.

Tier Two Powers - global presence and regional capabilities. On the cusp of superpower status in economic or military terms. Lack vital ingredients to maintain a global military deployment even if they are economically integrated with countries on the other side of the world.

Putin’s Axis - Moscow’s empire and its satellites, mainly Belarus, Syria, and North Korea. Badly damaged by war, it remains dangerous thanks to a large and well-developed nuclear arsenal. Determined to rewrite the rules of the world order, is fading fast but apparently determined to take the rest of us along with it.

India - soon to be if not already the world’s most populous country, India’s fast-growing economy has led many to bill it as an emerging superpower. However extreme internal tensions and lack of a real threat from outside mean it mostly keeps to its region in security matters. Nuclear power, but small and focused on retaliation only.

Japan - an economic and cultural superpower that appears to be escaping from a couple difficult decades on the former front. Not popular with a lot of countries in its region thanks to having tried to colonize most of them in the best European style, Japan is starting to emerge from the USA’s shadow and has some potent military capabilities, particularly at sea. Non-nuclear power, but could have nuclear capabilities in a matter of months.

Tier Three Powers- global connections and local capabilities. These are middle powers, able to defend themselves and probably win a war against any invader. Most boast a domestic military base actively seeking international markets, often with highly competitive products. While often part of alliances, are clearly a distinct member with their own interests.

This post is getting a bit long to give each the treatment they deserve, so here’s a simple list: South Korea, Turkiye, Brazil, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iran, Israel, and of course, Ukraine.

Each has its own distinct local concerns and military focus, but all could defeat a Tier Two power that tried to attack and likely even fight a Tier One power to a draw if it was foolish enough to launch a direct invasion. Only Pakistan and Israel have nuclear weapons, but all could in a few years.

The rest of the world is best grouped into regions where no country predominates and all have patrons or backers among the bigger powers. In these areas individual countries or even small groups may fight, but none can win a decisive victory without external aid. As such, they are diplomatic hotbeds where everyone competes, a situation that can be conducive to development or conflict.

Obviously this is far too short a treatment than is proper for such a weighty subject as the evolution of international relations. And I haven’t even had a chance to dive into the mechanisms that have been at play as the European World System evolved after each collapses.

What is key to keep in mind is that the Ukraine War is not the sort of conflict that can be put in a box or frozen again. Putin’s choice to attempt genocide has left the world with a stark choice: shrug it off and accept that this is just how life will be from now on or whether this sort of aggression is obsolete, more trouble than its worth.

It is simple, straightforward principles that ordinary people see as fair and just that serve as the ideal building blocks for a better turn in the ever-evolving global system. In every case where a degree of peace between powerful countries became the norm, even for a little while, those who could invested in rules like no, you can’t revise borders by force or yeah, we’re never letting kings fight wars over religion again that were backed up with physical force. When these degrade is when things fall apart, and new rules are laid down.

Thing is, there is no guarantee which direction the system will be yanked. If those who are willing to trample any rule in the name of their in-group’s declared interest are not stopped, they can also set a standard that is difficult to upset until the next turning of the wheel comes again.

There exists in the decentralized, global network of power relations the possibility of creating a new, more sustainable order. One that even breaks the bitter cycle of violence that has plagued imperial systems since their beginning. But you only get there if the kind of behavior that Putin has engaged in is slapped down the say Saddam Hussein’s was in 1991.

The flavor of the future is often shaped by the courage of a few people in the right place at the right time. A silent tragedy of the Ukraine War is that it was preventable: Putin has shown a marked hesitation to expand the war into NATO territory even though supplies from abroad are essential for Ukraine to hold the line and push back the invader.

Had a brigade from the 82nd Airborne division been dispatched to Hostomel Airport north of Kyiv in January of 2022, when the Biden Administration began proclaiming invasion to be imminent, Putin would have called off the attack. He calculated that NATO might huff and puff and expand to Finland and ship a few small missiles to show how angry it was about the whole thing, but otherwise stand back and allow Kyiv to fall.

And he was right. Had you told an American voter in 2020 that Joe Biden would make this choice, he would never have been elected. And that’s not a partisan position, it’s a simple read on how American politics operates. Part of the reason that Biden remains so deeply unpopular despite Ukraine’s victories is that all except the pundit classes perceive him as having failed to stop or win.

It’s missed expectations like these that signal to all the world that the powerful might not be as tough as they claim. That invites those with ill intent towards their neighbors to test the waters. All like them around the world watch and learn.

The best way forward is to back Ukraine all the way. Some policy questions are, in the end, very simple.

If someone sets your friend’s house on fire, you don’t hold back the hose out of fear the arsonist will come after you next. If you do, he will. If you step up, the bully steps back - or else he’d have come at you to begin with.

Interesting article. Also, I've enjoyed your updates no the War in Ukraine -- keep those up!

I have a few responses that you might find provocative.

1. If you're interested in how systems are formed and then disintegrate, only to be reformed in various ways in a new paradigm, you should spend more time thinking about the *forms* that elements of these systems take, and how these forms manifest themselves rhythmically. For example, the last century of Russian history has revealed that the Tsarist concept that started to coalesce after the Muscovites threw off the Mongol yoke has remained the same fundamental mode of cyclical national/cultural formation, despite different ideological and historical window-dressing in different cycles.

If you want a fundamental theory of international relations, wars and personalities and Big Events, if treated as specific contingencies, will abstract to concepts that have limited general applicability. A better approach, in my view, would be to develop a taxonomy of procedures and power relations within governmental bodies & their territories of industrialized societies, and then a theory of how different combinations of these procedures and power relations project outward under different conditions. I'm not deep on this subject, but just in reading the reporting and analysis on this war and on other current and historical events, I see little evidence that people working in history and political science are good at devising and organizing categories. So chaos at the level of "systems" is illegible; too much time is spent trying to establish fuzzy causal explanations for everything. I'll note that in saying this, I wouldn't want anyone to think that I'm denigrating good, detailed descriptive work; descriptive work is the feedstock of explanatory work.

2. I think you're too pessimistic about the US and its future. If Trump gets elected in 2024, we're in for a rough time for the next few decades, and there's always a chance things could snowball from there. But if we can dodge that bullet, we'll muddle through and still be the world's leading power at the end of the century. If Trump has no formal power after Nov. 2024, he will end up in jail and/or dead, and I don't believe any of these other reactionary clowns will be able to attract the same level of support for an authoritarian program at a national level. We'll settle back to business as usual -- fucked up in certain ways, but also stable enough that people can get on with their lives. You discount too much the long-term upside of muddling through.

3. The big events after 2050 are going to center on South Asia and Africa, and these barely figure into your "powers" scheme. I have no idea how the rise of these regions will play out, especially with the effects of climate change on tropical regions, but the demographic projections should warn us to expect massive changes later in the century. If we can contain China and Russia for the next decade or so, America's future as a leading power will hinge on our relationships with India and the most populous Sub-Saharan African countries. In the medium term, we should be looking to encourage immigration from those countries.

4. The BIG paradigm shift that we're grappling with globally is not political but cultural and economic. In the last ~250 years we've moved from an agrarian world (incipient in the mercantile, colonial order established by the European powers from the 1500s onward) to an industrialized world. Many of most fervent ideas about what makes a proper society are downstream from this structural shift, and it cuts across all typical divisions of east and west, north and south, this language or that language, this regime or that regime. America's power is geographic and demographic, in part, but our history as a nation has also exactly tracked the development of industrialization with less interference from the agrarian Old World than, basically, every other region on the earth.

It seems to be a series of opinions. I did not see any theory.