Ukraine's Fall 2024 Campaign: Counteroffensive Options

With Ukraine ahead of the rough schedule for returning to the offensive that I posited this spring, it's worth considering where Syrskyi may make his next big move.

To my eye, it’s apparent that Ukraine has big plans for the upcoming fall despite ongoing ally-induced shortages of modern equipment. Moscow’s inability to reclaim Kursk and the slow deterioration of offensive efforts on numerous fronts suggest a military power on the wane.

A large ruscist counteroffensive appears to have finally begun in Kursk, but it’s much too early to tell whether one of Ukraine’s brigades took a hit or Ukrainian forces are in the process of destroying the wave of attackers that drove south from Korenovo. Should know more by Monday - initial impressions are often inaccurate, so I’ll refrain from speculating.

Putin’s refusal to dial back his sputtering Donbas campaign has created a situation reminiscent of September 2022. Chronic issues with getting quality information about the real state of affairs along the front makes it impossible for Moscow to set effective policy or develop a viable strategy for victory.

Ukraine has one, but implementation continues to be held back by allied leaders who act suspiciously like they’ve been compromised by the FSB. Under Syrskyi, Ukraine is now six months into a deliberate effort to reclaim the strategic initiative. Moscow has to be induced to stretch itself thin before a series of sharp counterattacks can develop into bigger breakthroughs.

The rhythm is the same in every war: technology has only altered the pace of the dance, as it does every now and again. Military institutions in the democratic world are failing to keep pace because they’ve decayed, leading to a widespread inability by prominent experts and key leaders to grasp Ukraine’s natural path to victory.

Contrary to popular mythology, effective military command does not flow from the genius of some ego-driven Napoleon wannabe. Badly misunderstood by most people who cite or criticize him, Clausewitz was an early systems theorist who sought to apply scientific principles to counter the pernicious myth of genius.

After getting trounced by Napoleonic armies mostly powered by sheer numbers, European leaders latched on to the myth of his unique military genius to explain their inability to contain French forces for so long. Clausewitz and the Prussian reformers who he inspired transformed their country’s defeated military along different lines, paving the way for the Prussian-led unification of Germany that roiled European power politics straight through to 1945.

They did it by recognizing that genius is a product of organization, not birth. The root kernel of all combat power is small teams seeking to accomplish a mission in the face of opposition.

War isn’t any different than investing or even gardening - it’s all about deploying power to achieve concrete aims that build on each other, the collective riding the waves thrown by mother nature. On the battlefield, there are no individuals, because these soon die. To avoid getting hit from a direction you aren’t looking requires a team.

Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, Boyd - every big-name war theorist ever has ultimately been making the same underlying case: war is a complex affair because people are involved, and this generates uncertainty. Preparation and planning are essential because they are able to remove as much uncertainty as possible. But still, in countless small moments, small teams in contact with opposing forces make decisions based on a select few variables, most hinging on their own survival.

Theory is important in science because it helps identify which variables matter in a given context. Americans are trained to see science as a set of facts established by experiments interpreted by authority, but even the most rigorous empiricism is only half of the full process. To decide what facts actually count as such requires a consistent external logic. Inductive and deductive reasoning have to fit together; they are not substitutes.

In addition to laying out where I think Ukraine will strike, I’ll also describe how I go about making such a forecast. I wouldn’t try, being a remote observer, except that I’ve seen both sides in the war make operational moves that I previously predicted. Not because I possess any special ability, but because I’ve wound up with an unusual combination of training and experience that today’s fragmented education system rarely produces.

Moscow’s advance into southern and eastern Ukraine back in 2022 was eerily similar to my projections. Months before Ukraine liberated Zmiinyi (Snake) Island, I noticed what someone in Ukraine also did: that it was within range of NATO standard artillery, if guns could be safely operated from a nature preserve on the mainland. Shelling beats air defenses, French Caesar and Ukrainian Bohdana wheeled howitzers (one of each) enabling the amphibious assault Ukraine later mounted to retake this crucial bit of real estate, key to Ukraine’s exports, much of it food.

Months before Ukraine launched the counterattack in Kharkiv that retook Kupiansk and forced the orcs out of Izium, I spotted the potential - Syrskyi, who supposedly planned and ran it, had to have remembered how the Soviets were mauled by the Germans in the spring of 1942 in this exact same area. I could also count the liberation of Kherson and the general location of Ukraine’s summer 2023 counteroffensive on the Azov Front, except these were so obvious that even the usual nincompoops in D.C. and Moscow saw them coming. And unlike nearly all observers, at least according to the big names in the business writing in recent months, I correctly predicted that Ukraine would launch a major counteroffensive wave in 2024 and not wait until 2025.

Many analysts and observers broadly predicted the same Ukrainian moves; I’m just trying to evaluate what’s happening from a scientific perspective, seeking a foundation for reliable prediction. I happen to think everyone in a democracy should be able to plan and execute a basic military offensive, or at least understand how they work. That way, when wars happen, fewer people are convinced to do stupid things like invade Ukraine.

Former and serving mid-level military personnel on both the officer and enlisted sides almost certainly understand what’s really happening soon after news breaks. They just don’t get invited on TV, journalists preferring to interview politician-generals and ambitious retired colonels.

Real pros spend their careers living what I’ve wound up dedicating a huge part of my life reading about.. A year in uniform under the tutelage of some fine sergeants anchors all the book learning, serving as a constant reminder that official reports are only ever half the story and official histories even less.

My broader mission in writing this blog is to apply what I know from spending a lot of years in higher education to breach the barrier separating military and civilian science. A truly astonishing amount of money around the globe is spent every year on policy measures derived from what amounts to pseudoscience. A few people generate a lot of income by exploiting the lack of general public understanding of the science of war and warfare.

This also filters back into the civilian world, powering an endless stream of corporate fads revolving around imitating supposed military practices. Eventually the same consultants make their way into defense management circles, producing a lucrative but self-destructive loop. Academics show up to codify this situation as somehow innovative, and eventually the blind are leading the deaf at every level.

I’d love to set up an institute or something to counter this, and eventually I hope to get hold of sufficient resources to get a sustainable effort going. I happen to know of a small local university that could sure use an infusion of external investment…

In the meantime, as I work on getting a book project or two bought by a publisher instead of doing everything solo, I’ll start trying to include more information about how I generate forecasts. I didn’t always look at a map and see where armies will want to go - it’s a skill that can be learned, like any other. That’s another angle of the institution I’d love to build - simulation based training through wargames.

Conceiving A Campaign: The Relationship With Strategy

Deep down, planning a military operation is a lot like organizing a school field trip. I grew up in a part of California where every year several classrooms were bussed up to the local volcano for the day. Yes, California has volcanoes. It’s less one big beach and more a giant farm sandwiched between two coastal megacities and tall mountains, with the ones apt to explode being way up north, near Oregon.

Collecting and moving a hundred kids, enough supplies to keep them fed and hydrated, buses and fuel, chaperones, and all the other bits and pieces required is no walk in the park. Now imagine doing all that while getting shelled, drone-bombed, or shot at.

A military counteroffensive of the size Ukraine needs to breach a defended front involves combining the efforts of about a hundred units of this size - thousands of people in all. Their work has to be done in the proper sequence, coordinated to avoid friendly fire accidents or traffic jams that will attract ballistic missile strikes. Not only that, but for every hide constructed to hold a vehicle, supplies or group of people, a backup is needed.

Military operations rely on surprise, meaning that as much of the preparation and execution as possible has to be done covertly. An already difficult puzzle thereby spreads to an entirely new dimension, creating a landscape full of opportunities for the enemy to discover and exploit. Moscow runs its wars like an AI from a computer game, but that doesn’t make it less dangerous to soldiers on the front line.

With there being so much that can go wrong in the simplest movement of forces across a battlefield these days, small wonder casualties in the Ukraine War are so brutally high. That makes it absolutely vital to choose where you fight with the utmost care.

How does a planner make this choice? Ultimately, they have to weigh all the potential confounding variables against what they know their forces can actually accomplish. This isn’t easy to summarize, with context always defining the details, but certain principles are universal enough.

Any operation is a physical expression of strategy, which is best defined as an applied theory of building a desired future. After assessing the factors that constrain the strategist’s freedom they must choose between concrete actions that represent a logical investment of resources. Note that this conception of strategy is scale independent - it defines a process underway at the level of the country and squad alike.

Operations involve putting resources to active use. In a military conflict this always revolves around destroying the enemy’s ability to deploy combat power. This is the physical chain connecting policy and action, with strategy modified as operations reveal the truth about the combatants’ relative strength. Every action is an experiment that generates new data, requiring revision of standing theory.

The landscape that combatants fight upon fundamentally underpins the operational choices available. Topography and roads predetermine a great deal of what is possible, directly affecting how many soldiers an enemy needs to defend a particular area and how hard it is to supply troops in or beyond it. Deciding how much combat power to deploy where is a never-ending puzzle, a series of cost-benefit calculations that shift as new information about the enemy emerges.

Every military institution around the planet has its own formula for coping with the chaos: Doctrine. A kind of meta-tactics, Doctrine is a combination of procedures, rules of thumb, and other heuristic management devices that seeks to define the ineffable ebb and flow of active combat. All Doctrine is alike in that it seeks to make joint efforts more focused and predictable; at heart, it’s applied science focused on smooth cooperation.

Doctrine is also limited by the landscape. One of the reasons I firmly believe that the entire Pacific region should be its own defense zone separate from the rest of the US military establishment, from factory to front line, is the unique challenges posed by the area’s geography. Americans outside the Pacific States just do not comprehend on a cultural level the differences between European and Asian geopolitics and probably never will.

Ukraine’s counteroffensive options in 2024 and 2025 are limited by substantial strategic and operational considerations. There are two strategic pathways to victory, restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

Option One: a political crisis in Moscow triggered by Ukrainian battlefield success that brings about a change of regime. Putin’s successor - likely a member of the inner circle who puts together an alliance including elements of the FSB, military, and oligarch class - is forced to retreat and seek accommodation with Ukraine’s allies. Putin becomes an easy scapegoat, and even if the regime is officially hostile to Ukraine it won’t be bound to Putin’s obsession with destroying it.

Option Two: the total battlefield defeat of Moscow’s occupation forces in a sequence of campaigns that isolate Crimea and urban Donbas; a buffer zone is created along the international border involving the long term occupation of portions of Kursk, Rostov, and Belgorod. Putin is forced to turn to tamping down regional rebellions, if he isn’t overthrown in a coup that very likely leads to a bloody civil war. Ukraine, badly damaged, will turn to reconstruction with a wary eye on the unsettled eastern frontier.

This year, Ukraine needs to deliver a decisive operational defeat that stretches ruscist forces beyond their ability to defend the entirety of occupied Ukraine and Free Kursk. In the best case scenario for 2024, Crimea will be physically isolated by Ukrainian occupation of the rail line passing between Rostov-on-Don and Crimea. A rollback of ruscist forces in the east would represent a mid-level win.

The approach of winter is a major factor in Ukraine’s calculations. It has been a warm and dry summer across most of southern and eastern Ukraine, with precipitation at below average levels. This isn’t great for farmers, but after a relatively dry winter and abbreviated spring mud season the conditions look ripe for major ground operations to continue well into the fall - maybe past the end of the year.

In general, winters aren’t what they used to be in eastern Europe thanks to the warming climate. Where a distinct winter fighting season used to be feared by German forces on the Eastern Front, as the Soviets would often use it to cross frozen rivers and assault thinly-held lines, now December through April is basically a single muddy season with a few deeper freezes.

Tracked vehicles do alright in this weather, and minefields are more difficult to sustain. But people can’t fight for very long during the cold snaps, wheels get stuck in mud, and drone battery charges decline faster in the cold. The pattern the past two winters has been for Moscow to maintain a steady stream of assaults with small groups while Ukraine conserves its strength. However, northern and southern Ukraine are not the same in terms of their climate or the way their soil interacts with precipitation. Generally, winter is worse up in Kharkiv but more tolerable down in Kherson. This constrains the pace of major operations.

The most important environmental factor of all in the drone age is probably the amount of cover. Once the leaves are off most deciduous vegetation by late November, moving undetected becomes much harder. That plus mud can be fatal for wheeled vehicles and anyone on foot, though in bad weather drones are tougher to operate. If Ukraine can secure drone superiority over an area for a few days, lack of cover may allow it to perform efficient recon and clearing operations.

The fighting in Ukraine looks set to intensify well into December before tapering off somewhat until April or May. Ukraine won’t be compelled to cease offensive operations entirely at any point thanks to apparently secure and growing supplies of artillery shells. It can’t let the pace of casualties inflicted on the orcs slow, because these have exceeded replacement levels since spring, generating a shortage of ruscist reserves.

My expectation is that Ukraine should be able to launch more two offensive waves after the first, which invaded Kursk, has fully culminated - as it might now have. Each will last 6-8 weeks, though active phases may overlap, one effort beginning in mid to late September and lasting through November, the other starting in late November and carrying on until the weather worsens.

Both will involve 8-12 brigades, the core of the latter wave comprised of brigades being pulled off the line right now - 47th and 72nd Mechanized, possibly 82nd Air Assault or 80th Air Assault if they rotate out of Kursk soon. The September wave could prospectively be lead by 21st, 66th, 44th Mechanized, 3rd Assault, and 38th Marine Brigades. About a dozen brigades of the 150 and 160 series are presently forming up, so they should arrive in the coming months, replacing veteran brigades on the front or joining offensive groupings.

The fact that most of the reinforcements flowing to Pokrovsk and Toretsk appear to be coming from Ukraine’s Offensive Guard brigades seems noteworthy. Stiffened by a well equipped regular brigade or two, the combination has performed quite well halting ruscist operations in Robotyne and Vovchansk.

This tells me that brigades more suited to breaching defended orc fronts are bulking up for future deployments. When they are committed, Ukrainian brigades in the affected areas as well as those stripped bare of troops by Moscow will get relief and a chance at more frequent rotations.

By striking Kursk, Syrskyi has forced Moscow off balance. Instead of applying pressure almost everywhere while making a hard drive for Pokrovsk, Moscow is having to wind down activity on some fronts to cope with Kursk. With the risk to ancillary fronts now reduced, Ukraine is able to reinforce more at-risk ones.

Overall Syrskyi appears to be a step ahead of the orcs, so committing the next batch of operational reserves (assuming they exist) ought to generate a major crisis for Moscow. Putin will have to choose between ending the push on Pokrovsk or pressing on while demonstrating an inability to repel Ukraine from Kursk while yet another front faces collapse.

If Moscow throws everything it has at Pokrovsk, it could probably take the place by the end of 2024. The cost - aside from another forty or fifty thousand casualties - will almost certainly be one or even two additional successful Ukrainian counterattacks that might even cut the railroad to Crimea.

Ukraine has destroyed Moscow’s ferry system, sunk or driven away its landing ships, and damaged the Kerch Strait bridge enough to significantly reduce its load. The thing is eventually going to take a hit again, putting all Moscow’s eggs in the already vulnerable overland rail basket.

A Simple Menu of Operational Choices

The first step on the path to victory is breaking Moscow’s combat power in the field by forcing it to respond to Ukraine’s blows as they land. The past few months have seen Ukrainian soldiers normally serving away from the front make the sacrifice of enduring meat assaults until newly mobilized personnel are trained up. The first fresh soldiers have arrived in force, Ukraine now able to train as many as Moscow does in a month.

Thanks to most of the adult male population having served for a year as a conscript, their refresher training can apparently be handled in about a month. After that they spend another month to six weeks with their assigned brigade doing intensive drills before seeing the front lines. That appears to be the standard, anyway: some leaders cut corners to boost their reported numbers in any army. This is bad, but it’s hard to combat that kind of corruption - soldiers have to stand up for themselves and get support when bad apples retaliate.

Ukraine and its allies have ramped up training programs over two and half years, but quality is bound to be uneven. Line units are finding it necessary to do most of the real training, pulling new soldiers into battalions presently assigned to the reserves. This isn’t ideal, and speaks Ukraine’s lack of institutional capacity. Eventually, best practices developed by Ukraine’s top brigades need to be used to produce a unified curriculum. Though America’s has many glaring flaws, the ability of one battalion to substitute for another of similar composition in a totally different brigade with minimal friction isn’t one of them.

On the flip side, Ukrainian brigades become intimately familiar with their area of responsibility. In general having personnel move between line units and training formations at various points in their career development appears ideal, and eventually Ukraine has to establish a comprehensive system for this. Having brigades become attached to particular areas while battalions become interchangeable might be a good balance.

All in all, it looks as if Ukraine can replenish about a dozen battered brigades every two months. Knowledge that the bodies were coming let Syrskyi commit his existing operational reserve to Kharkiv in May, once Moscow had revealed where it planned to open a new front this summer. By August, the first new operational reserve was almost ready, enabling Syrskyi to commit most of the brigades assigned to Kharkiv plus a couple pulled in from other fronts to hit Kursk.

This implies that by late September the next echelon will be deployed, with brigades coming off the line now ready to return by mid November. While this sounds ridiculously fast, and is by American standards, 110th Mechanized went from being forced out of Avdiivka after two years to holding the line once more north of Ocheretyne.

Somehow Ukraine is managing to keep its brigades in working order despite pathetically inadequate resourcing from its allies, and I commend whoever is involved with making that happen. As as far as what to do with its combat power this fall goes, the question is where they can hope to achieve the greatest possible effect.

There’s no uniform way to encapsulate every possible operation. So here’s a broad list of considerations that go into deciding where to mount one:

How far do my people have to go to reach their objectives? Effective strength declines with distance.

Where along their routes does the terrain restrict movement or create places to hide? That’s where the enemy will set traps - beware water lines and canyons.

How far are the nearest enemy supply bases that we can’t hope to seize? Intensity of counterattacks scales with proximity to logistics nodes.

Does the terrain allow us to advance down a slope? Make gravity your friend; less energy wasted means more left for destruction.

How ready is the enemy? Weakened, distracted, or neglected formations are often the link in the chain that breaks first.

Can I keep my squishy types safe? Artillery, logistics, medical, supply - they all need secure, camouflaged bastions to operate.

For how long can efforts be sustained? Moving to a target to raid it, annihilate it, or seize lasting control are different ops requiring different resources and plans.

If we succeed, does it even matter? There have to be measurable objectives and success must disrupt or damage the enemy’s military system.

Assuming the enemy works out my plan, what’s the fallback? It’s entirely possible to seize victory from the jaws of defeat with a solid Plan B, and stuff always goes wrong.

I think it’s fairly obvious that there’s an endless list that can be constructed. Maxims and principles have been suggested by far more experienced and capable minds than mine for centuries. These just cover enough ground to give a sense of what’s actually going on in the head of a planner - or forecaster role-playing one to derive insights.

Even bigger questions heavily structure an operation, but once aware of the resources available and grand constraints like political aims and the weather, the task of siting an operation remains. Not every spot on the battlefield has the same value in terms of acting as a step on the shortest road to the end of the war.

For example: cities like Melitopol, Mariupol, Kharkiv, and Kursk are often spoken of as if one side or the other is determined to seize a particular urban agglomeration, but cities are avoided in most operations. Like mountainous terrain, they tend to absorb attacking forces which find that there’s always another valley or building to seize unless the whole region is first surrounded.

Moscow has targeted cities directly for lack of a better option: being terrible at maneuver warfare, it prefers sieges, which are less dynamic and more engineering puzzles. Urban fighting is costly for both sides, so pulling Ukraine into it is often better for the orcs than trying to advance over open fields monitored by drones backed by artillery. Similarly, each side relies on dense patches of forest as defensive strongpoints even in offensive operations, securing these being critical to the survival of infantry.

Ukraine needs to be very careful with its people, seizing only territory which does disproportionate harm to the enemy relative to the casualties it costs to take and hold it. With supplies from its partners remaining shamefully limited in volume, Ukrainian operations have to be relatively shallow: a thirty to eighty kilometer advance over six to eight weeks.

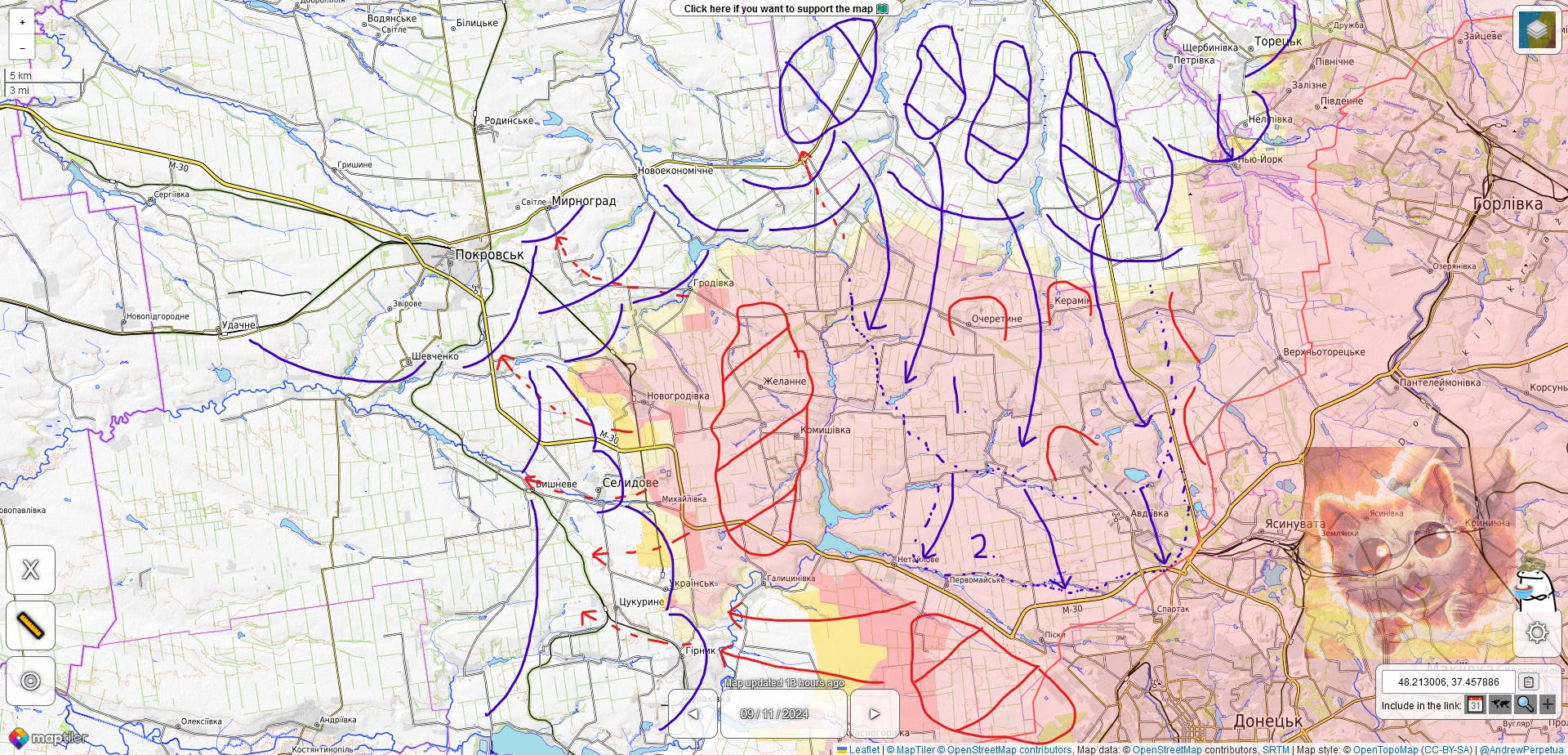

The first and most obvious target is the Avdiivka bulge. Here, Ukraine stands a very real chance of reversing nearly all of Moscow’s progress in 2024. Tens of thousands of casualties have sufficed to move Moscow’s forces thirty kilometers west along a front about as wide. Though the orcs are moving aggressively to secure the southern flank of the bulge, it remains potentially vulnerable to the north.

Ukrainian forces already have a large number of brigades here, making an influx of new bodies easier to disguise. Applying the Kursk template to Avdiivka, where reinforcements arriving to fend off an offensive in one place shift to a nearby sector and mount their own, a focused assault south from the Baranivka-Kalynove area could potentially breach the front, allowing Ukrainian troops to rush back into Ocheretyne.

From there, a successful assault could be followed by a push towards Avdiivka proper. While it is almost certainly a major garrison point for orc forces, if they’ve stretched themselves too far trying to advance to Pokrovsk and a sudden collapse of the outer lines panics local commanders, a chain reaction could allow Ukraine to seize positions in the town. Because the troops holding the fortress were forced out by an envelopment instead of burned out methodically by thermobaric and glide bomb attacks, if reclaimed Ukraine could probably hold it.

If Ukrainian troops could reach the M-30 highway connecting Avdiivka and Pokrovsk, they would cut off the second logistics route Moscow recently won after breaching the Vovcha line. The whole Pokrovsk push would transform into a pocket trapping a full ruscist field army tens of thousands strong. It would only be able to escape by moving south through Krasnohorivka, a release valve left open but bombarded to encourage retreat as opposed to a fight to the death.

Reclaiming Ocheretyne and severing the Avdiivka-Pokrovsk rail line would be a big win in and of itself, ending Moscow’s hopes of seizing Pokrovsk. Punching back into Avdiivka would be both a crushing battlefield victory and potentially also deliver a fatal hit to Putin’s fading legitimacy. The existing presence of Ukrainian forces and potential for killing two birds with one shotgun blast makes Avdiivka a very attractive target. Success would validate Syrskyi’s decision to retreat from here upon taking over from Zaluzhnyi and conduct a fighting withdrawal towards Pokrovsk.

There are a number of challenges, though. First, off, the move is obvious. Second, Avdiivka was a great fortress in operational terms, but holding it meant keeping Ukrainian troops within artillery range of the Donetsk urban area. For that reason alone it was always likely to prove harder to hold than Pokrovsk. Moscow’s combat power is chewed up by the drive to the front from Avdiivka thanks to Ukraine’s drones, and the same could be true for Ukraine heading the other way.

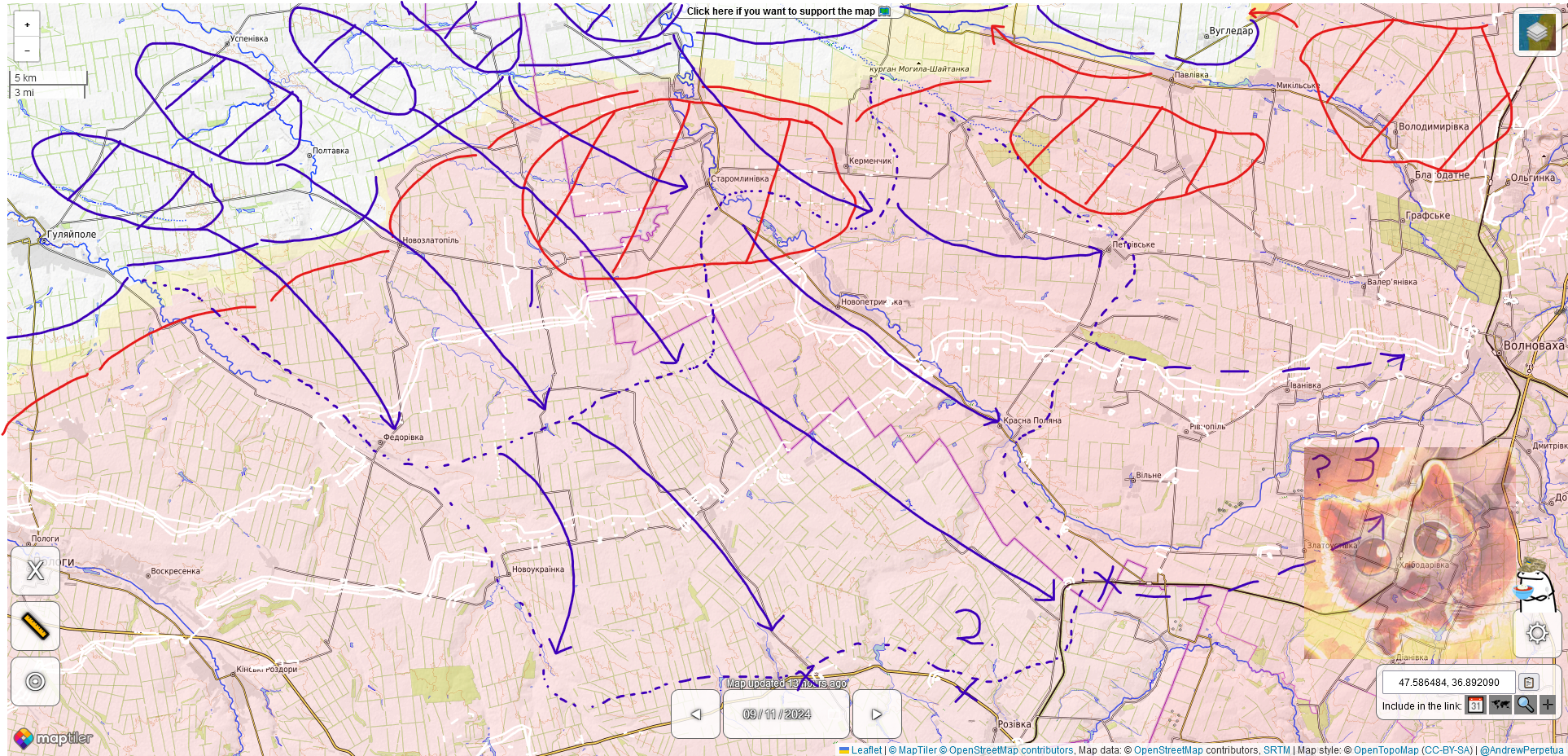

Next up on the menu is the Kamianka-Volnovakha axis, between the Vuhledar-Velyka Novosilka line and Mariupol. There’s a reason that Moscow has always maintained a secondary axis of advance in this area, aside from merely tying down Ukrainian forces, and that’s the vulnerability of Moscow’s entire position west of Mariupol to a sudden Ukrainian push of just forty kilometers to cut the rail line between Rostov and Crimea. Kursk saw Ukraine go thirty in days, so the concern is justified.

This op would be dangerous, but capable of achieving what Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive set out to do farther east. Ukraine’s push up the nearby Mokri Yali valley in May and June of 2023 worked in parallel with the bigger punch towards Tokmak, one threatening the land bridge to Crimea at Melitopol, the other Mariupol, with a bonus option of both turning to converge on Berdiansk in between.

The ground here is very open, rising gently up to the Azov ridges, and its more southerly position means that it should stay warmer longer than even the nearby Avdiivka area. If Ukraine can push the front even twenty kilometers closer to the rail line near Rozivka or Volnovakha, shelling and drone strikes can reduce its capacity. Moscow is increasingly having to rely on it to ship fuel to Crimea, rendering the sector a critical point of vulnerability.

Hitting here would advance both of Ukraine’s pathways to victory, but Ukrainian forces would have to fight uphill and cross several water lines, plus there are two layers of the Surovikin Line to contend with. A series of fierce counterattacks must be anticipated within a few weeks, though this would almost certainly end the Pokrovsk campaign, at least.

Moscow’s forces to the west - well over 100,000 and probably double that, would not be completely cut off from supplies, but badly limited. A subsequent Ukrainian operation on the Dnipro Front would become very attractive.

Ukraine’s third natural option is a concentrated strike on the Svatove-Starobilsk axis, east of Kupiansk. In September of 2022 there were briefly high hopes that Ukraine’s liberation of Kupiansk, Izium, and Lyman would be followed by a push further east into occupied Luhansk district. Syrskyi wisely held his vanguard back then, sensing a substantial defense building up near Svatove.

With the region reportedly a source of reinforcements for Kursk, the front could be vulnerable. Up until Ukraine pushed into Kursk, any offensive in this area looked doubtful because of the presence of major orc bases just across the international border. But these might be targeted by a feint or even large secondary supporting strike, paralyzing orc forces to the north of Svatove. The main offensive itself could largely cut off those operating south from support, pressing them against the Siverski Donets river.

This is mostly rural country with few large settlements save along the river, so a breakthrough could lead to Ukraine shoving Moscow’s forces back a good distance. Even taking Svatove would be a win, but reaching Starobilsk would open the door to Ukrainian troops driving south to Sievierodonetsk and Rubizhne. If the ruins of these cities could be retaken, the Siversk bulge would be much relieved.

This option is perhaps no riskier than either the more obvious plays against Avdiivka and Volnovakha, though it is less immediately helpful in advancing Ukraine’s march to victory than both. It would take a lot of resources for Ukraine to liberate all of Luhansk and hold it.

But Ukraine would stand to liberate a lot of territory that could be used as a base for attacks on orc troops in urban Donbas from the north and send drones over the border to smash Millerovo airbase and the highway linking Moscow and Rostov. Keeping the door open to something of this nature could be why Third Assault Brigade, a large and experienced formation, was moved to the area a few weeks ago.

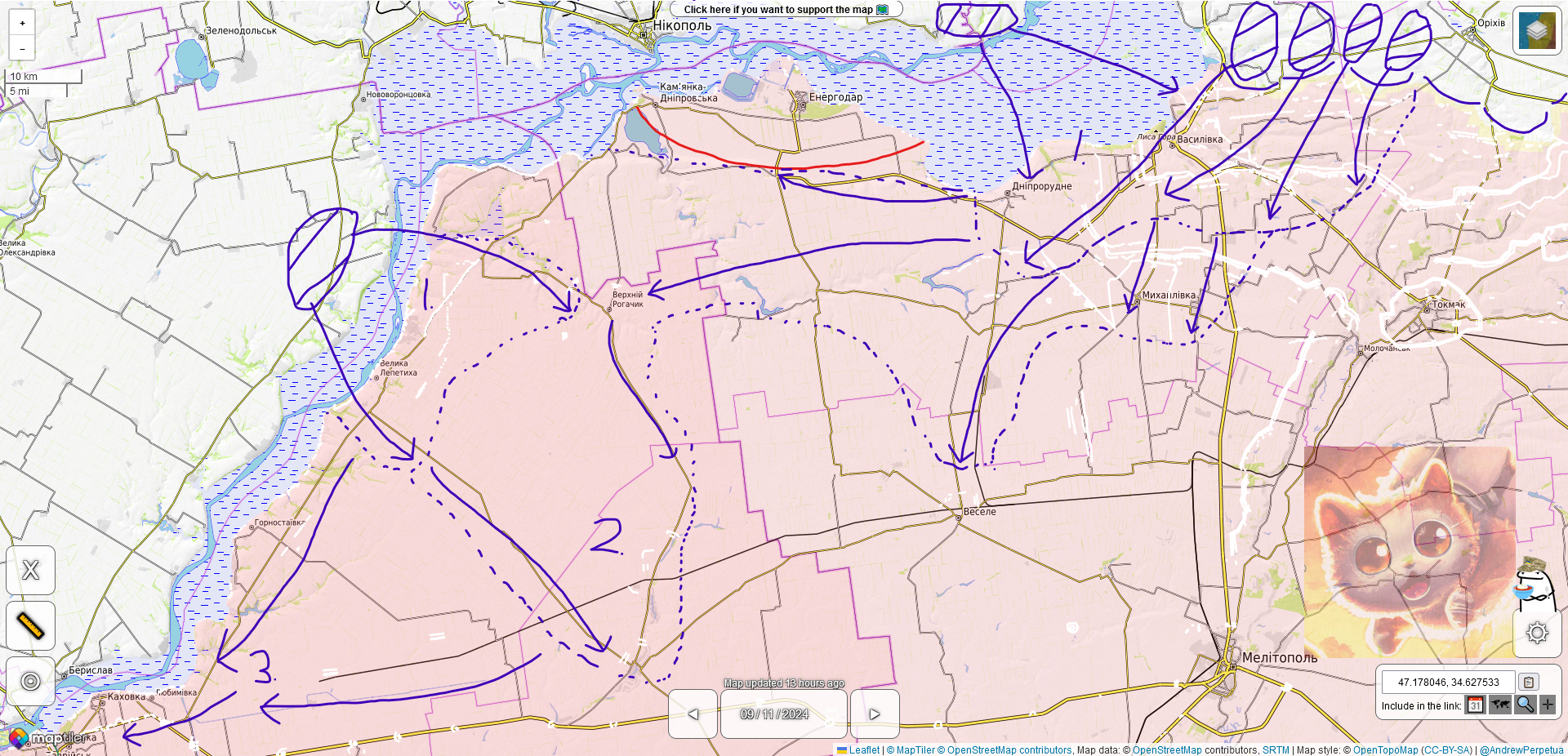

The fourth option for Ukraine is establishing a proper bridgehead over the Dnipro. I had hoped for a long while that the commitment of Ukraine’s Marine Corps in Krynky, Kozachi Laheri, Dachi, and other bridgeheads indicated a buildup towards something larger, but by early summer it became clear that wasn’t viable and Ukraine withdrew most of its forces.

I don’t think Ukraine has given up on crossing the Dnipro. It just probably can’t be a pure amphibious operation because of a lack of boats. This area is also the last in Ukraine where the weather will interfere with operations to the point they can’t build momentum. If Moscow is stretched by a new Ukrainian counteroffensive on another front in September and October, November and December might be suitable for starting a major campaign south of Zaporizhzhia.

This would combine aggressive raiding across the diminished course of the Dnipro while a much larger traditional ground assault grinds west through Vasylivka. A number of orc war bloggers appear to be sounding the alarm about Ukraine building up forces in this area, and they’re often a good leading indicator of important facts that Putin’s team will choose to ignore.

The core reason for Ukraine prioritizing the liberation of Crimea that a defeat of this magnitude will almost certainly finish what Kursk did much to advance - the final delegitimization of Putin’s regime in the only language that matters in his tired empire. If that won’t trigger a coup, it’s likely nothing will, and in that case Ukraine has no other choice but to demolish Putin’s military machine from leaf to root.

Success in any attempt to cross the Dnipro is a dicey prospect. This operation has haunted orc nightmares for two years; the risk of it happening is why they abandoned Kherson north of the Dnipro in 2022. Blowing up the Nova Kakhova dam and draining the reservoir in the summer of 2023 was part of an effort forestall any attempt while Moscow was pulling most reserves to Tokmak.

But this region has also become a source of reserves heading to Pokrovsk and Kursk. And even though the Surovikin Line is strong near Vasylivka, with three distinct layers to cut through, draining the Nova Kakhova reservoir might wind up biting the orcs.

Crossing a twenty kilometer flat to reach the enemy’s flank is far from easy, but Ukraine has lately demonstrated a growing ability to neutralize orc drones in an area for at least a few hours at a time using electronic warfare and drone interceptors. If Moscow’s generals were focused on an apparent effort to breach the Surovikin Line near Vasylivka, they might not appreciate the danger posed by a fast-moving Marine Brigade hitting the flank. Colder weather could be better for this sort of operation, as the terrain is presently wet and marshy, making a freeze helpful. Though at the moment Sentinel imagery shows the area being vegetated, which might mean more cover for infiltrating troops, at least until winter arrives.

What is actually possible on this front depends on the kind of knowledge only locals have to a greater extent than probably any other. But assuming that Ukraine can support a major push from Zaporizhzhia supported by landings across the length of the Dnipro, a drive that makes it eighty kilometers could isolate the occupied Enerhodar nuclear power plant. This and a crumbling of the enemy defense in the area more broadly could let Ukrainian forces drive down the south bank of the river to Nova Kakhova.

If Ukraine is in fact able to support two campaigns in succession, hitting Avdiivka then the Dnipro area would make a lot of sense. The first would inflict a serious military setback, straining the enemy’s resources to the greatest possible degree as the Kursk Campaign continues. The second could lead to Ukrainian troops standing at the gates of Crimea this winter, initiating a bitter siege.

Ukraine might instead hold the line in Pokrovsk and Kursk and throw its reserves fully into the task of isolating Crimea. That would entail moving on Volnovakha, then the Dnipro area. I can also see a great deal of purely military benefit in coupling an Avdiivka punch with one towards Svatove, possibly inverting the order, letting the orcs flail against the reinforcements protecting Pokrovsk while trying to cope with Kursk then eating a surprise attack on Svatove.

Concluding Thoughts

Now, it’s fair to question how publishing an analysis like this helps Ukraine. Though I do expect that some poor FSB and CIA case officers are forced to monitor this blog, I figure they have about as much power to influence policy as me.

Even if that judgement is incorrect, and I’m also somehow exactly right about Ukraine’s plans, well, that’s why I offer four options. Good luck figuring out which, if any, Ukraine will actually try. Ukraine always retains the ability to move faster than any independent observer can evaluate what’s happening on the ground. If Budanov’s people see evidence that Moscow is taking one or more of my proposed options very seriously, that automatically changes the calculus, creating a new opportunity for Ukraine.

What will surprise me in the coming months isn’t Ukraine attacking somewhere other than where I suggest, but it failing to attack anywhere at all. The winners of wars rarely sit back for two years waiting to have better capabilities. When the massive fleets of new ships and aircraft were finally available in 1944, Nimitz was already prepared to drive all the way to Japan because its forces had been ground down by a year and a half of counteroffensives.

Moscow is finally reaching the critical point in its stockpiles of armored vehicles and artillery barrels that portends a slow decline in the intensity of its operations overall. The orcs won’t go quietly, but eventually they will go.

It’s the duty and responsibility of Ukraine’s allies to equip it with the best kit available as fast as possible. Certain politicians in the USA might want to take credit for Ukraine’s survival, but they’re holding it back from victory out of rank cowardice. For someone who tried to bill himself as FDR 2.0 there for a time, Biden sure forgot FDR’s poignant lesson about fear.